Fossils unearthed in the Early Cambrian Sirius Passet locality in North Greenland have revealed an extraordinary discovery: a previously unknown group of predatory animals that ruled the seas over 518 million years ago. These massive worms, named Timorebestia—meaning “terror beasts” in Latin—are believed to be some of the earliest carnivorous creatures to colonize the water column, shedding light on a previously unknown dynasty of ancient predators.

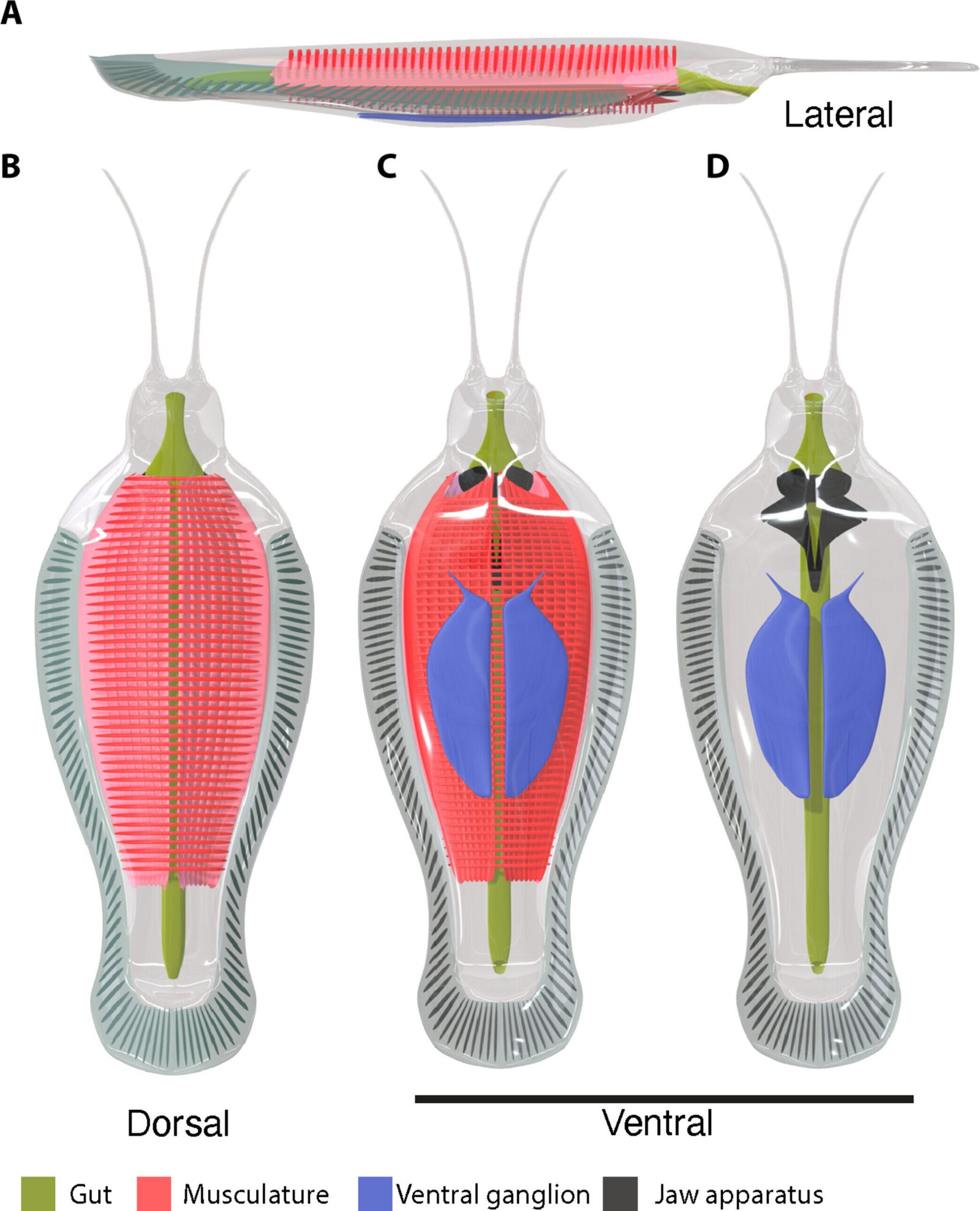

With bodies adorned with lateral fins, long antennae protruding from distinct heads, and enormous jaw structures, Timorebestia reached lengths exceeding 30 centimeters. This made them among the largest swimming animals of their time, a stark contrast to the smaller predators typically associated with Early Cambrian oceans. Their formidable appearance, combined with their advanced anatomy, establishes them as significant players in the food web during their reign.

Dr. Jakob Vinther from the University of Bristol’s Schools of Earth Sciences and Biological Sciences, one of the senior researchers on the study, commented on the find: “Previously, we knew that primitive arthropods like anomalocaridids were the dominant predators during the Cambrian, known for their bizarre and alien-like features. What makes Timorebestia fascinating is that they’re distant relatives of modern arrow worms, or chaetognaths—much smaller predators that today feed on tiny zooplankton. This discovery underscores the complexity of ancient marine ecosystems, revealing food chains with multiple tiers of predation.”

At the apex of their ecosystem, Timorebestia would have been ecological equivalents to modern apex predators like sharks or seals. Fossilized evidence within their digestive systems confirms their dietary habits: remnants of Isoxys, a common, spine-protected arthropod of the Cambrian period, were identified as prey. Morten Lunde Nielsen, a researcher involved in the study, explained: “While Isoxys had protective spines aimed at deterring predators, they clearly were not enough to evade Timorebestia, which consumed them in large quantities.”

Arrow worms, the modern relatives of Timorebestia, are among the oldest fossilized animals from the Cambrian, appearing over 538 million years ago. This predates even arthropods, which emerged between 521 and 529 million years ago. According to Dr. Vinther, the rise of Timorebestia represents a brief but crucial evolutionary period during which swimming predators dominated marine ecosystems before being supplanted by arthropods and other more competitive organisms. “These terrifying worms likely enjoyed a dynasty lasting 10–15 million years before they were surpassed by more successful groups,” Vinther suggested.

The anatomy of Timorebestia provides significant clues about evolutionary pathways that link them to their modern relatives. Luke Parry from Oxford University, also involved in the study, described how their features bridge evolutionary gaps. “Today’s arrow worms capture prey using external bristles on their heads, but Timorebestia had jaws inside their heads, more akin to modern microscopic jaw worms,” he explained. This discovery strengthens evolutionary connections between seemingly distinct organisms, painting a clearer picture of the origins of arrow worms and their anatomical features.

The presence of a ventral ganglion—a distinctive nervous system structure—provides further evidence of the evolutionary lineage. Found in both Timorebestia and a fossil called Amiskwia, the ganglion strongly supports their classification as part of the evolutionary stem lineage leading to modern arrow worms. Dr. Tae Yoon Park of the Korean Polar Research Institute, a senior author and leader of the Sirius Passet expeditions, highlighted the importance of this find: “The preservation of these unique ventral ganglia solidifies hypotheses regarding their evolutionary relationships and helps us better understand how modern arrow worms developed such distinct nervous systems.”

The significance of the Sirius Passet fossil locality cannot be overstated. Located in one of the northernmost regions of the planet, at over 82.5˚ north, the site boasts exceptional fossil preservation. This remarkable preservation enables scientists to uncover intricate details of ancient animals, such as muscle structures, digestive systems, and even neural anatomy. Dr. Park expressed his enthusiasm for the discoveries from Sirius Passet: “Our expeditions have yielded an incredible diversity of new organisms, offering unparalleled insights into the anatomy and behavior of these ancient predators.”

The researchers emphasize that Timorebestia is only one of many exciting discoveries to emerge from Sirius Passet. In the coming years, more groundbreaking research is expected, providing additional glimpses into the evolutionary story of Earth’s earliest animal ecosystems. According to Dr. Park, “Understanding how these ecosystems functioned and evolved is key to appreciating the origins of complex life and the dynamics that shaped early marine environments.”

The study not only introduces Timorebestia as a formidable predator of the Early Cambrian but also serves as a testament to the intricate and dynamic nature of ancient ecosystems. Through advanced fossil analysis and interdisciplinary research, scientists are uncovering the profound complexity of these prehistoric worlds, gradually piecing together the evolutionary puzzle of life on Earth. The full findings are published in the journal Science Advances.

Reference: Tae-Yoon Park et al, A giant stem-group chaetognath, Science Advances (2024). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adi6678. www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.adi6678