The U.N.’s Human Development Index (HDI), a widely recognized measure for evaluating human well-being and quality of life across nations, has recently been applied to the analysis of Europe’s first mega settlements by a team of archaeologists and philosophers at Kiel University. This innovative approach, published in the journal Open Archaeology, uses the “capability approach”—a philosophical concept championed by Indian economist and philosopher Amartya Sen—as a new method to interpret and understand archaeological data, particularly the social structures, identities, and living conditions of ancient communities. The researchers focused on the Cucuteni-Trypillia societies, which existed between 7,000 and 5,000 years ago, examining how human well-being can be reconstructed from static material remains like pottery, bones, and house foundations.

The “capability approach,” while traditionally used in social sciences to measure well-being and development, has rarely been applied in archaeology. The capability approach argues that human well-being is not just about material wealth but about the freedom and opportunity individuals have to lead active and fulfilling lives. This freedom comes from the ability to access resources, exercise individual and collective agency, and have the capabilities to innovate and participate in society. These ideas have been taken further by the United Nations and distilled into the HDI, a widely accepted measure that assesses national well-being through indicators such as education, life expectancy, and income. Yet, how these indicators could be interpreted from the remains of ancient cultures has been an ongoing challenge in archaeology.

Using the capability approach to analyze the past involves understanding how ancient societies gave their members the ability to improve their lives. As the researchers highlight, traditional methods of analyzing archaeological finds often only reflect a society’s material culture—tools, housing, food sources—but fail to provide insight into the less tangible aspects of life, such as social equality, opportunity, and innovation. This is where the HDI’s focus on broad and multidimensional aspects of human development becomes relevant. By considering not just the physical remnants but also the social dynamics and opportunities these societies may have offered, archaeologists can gain a more nuanced understanding of how these communities were organized and why they flourished.

One of the key factors in applying the capability approach to archaeological studies is drawing connections between material culture and the broad societal indicators used in modern well-being measures like the HDI. For instance, innovations in agriculture and technology provide a good starting point. Prof. Tim Kerig, one of the study’s authors, explains that new tools, technologies, and innovations such as plows and weaving looms were often introduced at points of socio-political or economic change. These innovations could increase the standard of living and allow people to expand their potential to act within the society. In large settlement societies, such as the Cucuteni-Trypillia, these innovations were likely connected to increasing resources, improved productivity, and overall human capabilities. By investigating these trends, the research team can begin to trace how the foundations of large settlements were laid down and sustained—not only through material expansion but through expanding the ability for individuals and groups to take part in shaping society’s future.

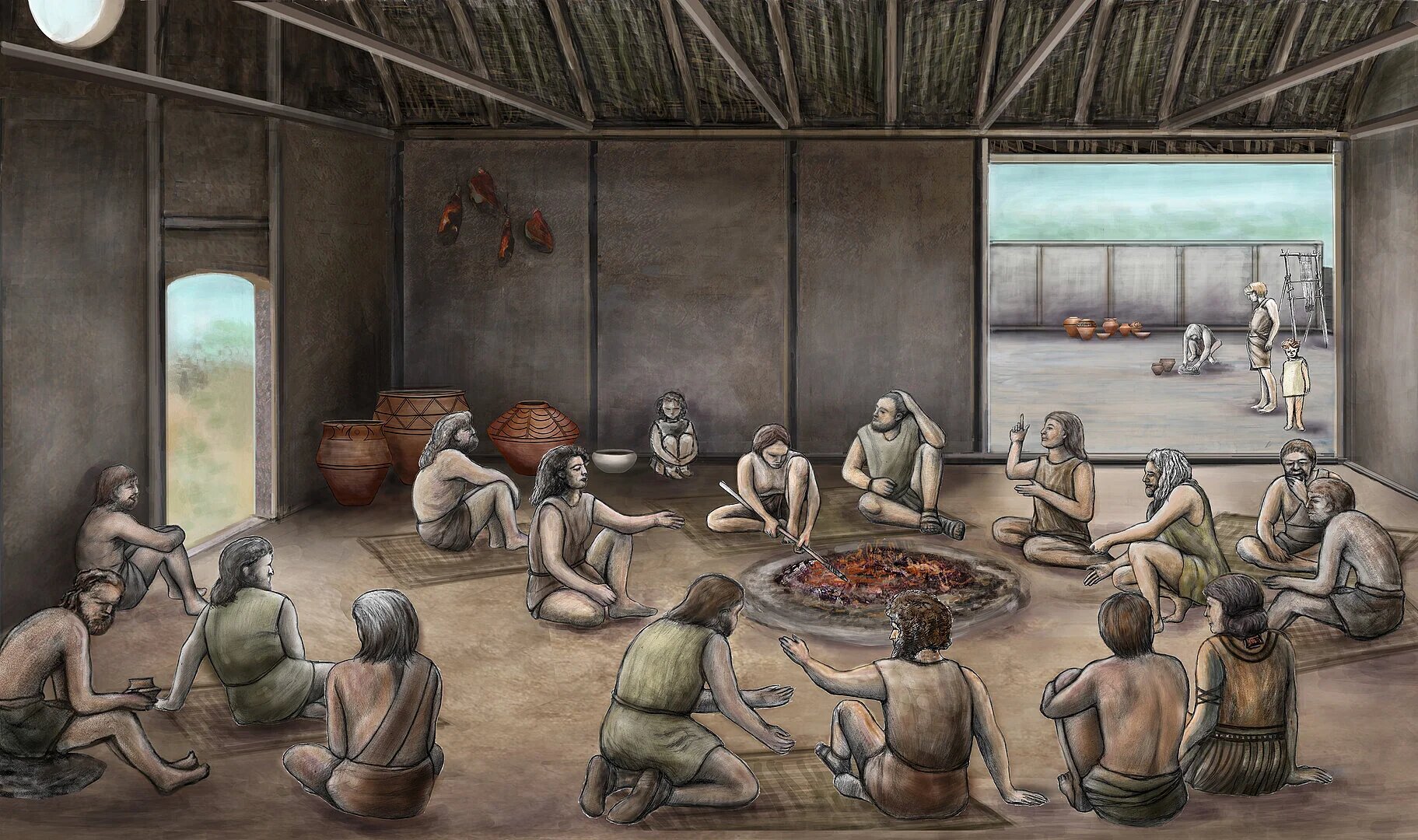

In their case study, the team focused on the Cucuteni-Trypillia culture, a society known for establishing some of Europe’s first mega settlements—massive ring-shaped villages that spread across what is today Romania, Ukraine, and Moldova. These settlements, which at their peak could hold as many as 17,000 inhabitants and cover more than 320 hectares, challenge traditional notions of early human settlement structures. While these societies are often characterized by their large size and complexity, archaeological research has historically focused on explanations involving environmental triggers—such as population pressure and climate change—as the driving forces behind societal changes. The idea was that increasing pressures led to population growth, which in turn sparked innovations and social changes.

However, the Kiel University researchers propose an alternative interpretation of the Cucuteni-Trypillia phenomenon. Using the newly developed analytical tools based on the Human Development Index and capability approach, they argue that these large settlements were able to thrive not because people were simply reacting to crises or external pressures, but because they offered expansive opportunities for social interaction, personal development, and innovation. By providing citizens with the “capabilities” necessary to shape their own lives, the settlements themselves became attractive to people from surrounding areas, stimulating growth and innovation in return.

This reinterpretation places less emphasis on external stressors and more on the internal, human-driven capabilities that could foster growth and sustainability. In this view, it was the opportunities for individual and collective action that fostered the expansion of the settlements and their prosperity, rather than environmental factors or population pressures alone. As Dr. Arponen explains, this framework provides an avenue for understanding how prehistoric societies may have been governed, structured, and organized—potentially highlighting how ancient communities created social and political environments that promoted widespread agency, equality, and collaboration. These conditions could have ultimately contributed to the settlements’ lasting success.

The implications of this research extend far beyond the Cucuteni-Trypillia culture. By applying the capability approach and HDI framework to archaeological data, the authors argue that we can gain deeper insight into other ancient societies as well. The methods developed in this case could be applied to a wide range of archaeological contexts, providing fresh perspectives on the successes and failures of ancient civilizations. The researchers assert that these methods could open new pathways for understanding how societies thrived in a variety of environmental and social conditions—making the case that it was not just material advancement that marked successful communities, but also the systems that empowered individuals and groups to engage in self-improvement, innovation, and social growth.

Furthermore, this research challenges the traditional explanatory models often used in archaeology and social history. By using the HDI framework, the authors push the field toward considering human well-being and social structure not as afterthoughts to material culture but as integral parts of understanding why societies thrive and how they develop over time. As the study of ancient civilizations evolves, new analytical tools like these will help broaden the scope of what constitutes success in human history. Whether the conditions leading to growth were external pressures, opportunities for innovation, or something in between, the ability of a society to foster agency and facilitate individual and collective action may be just as important—if not more so—than the physical remnants they left behind.

Finally, Dr. Arponen emphasizes the potential long-term impacts of these ideas on archaeological research. By adopting frameworks that move beyond traditional explanations and focus on human agency, agency across different cultures, and broader definitions of development, archaeologists can encourage a richer and more diverse understanding of our collective human past. Rather than only assessing ancient cultures through material culture and survival rates, the capability approach allows archaeologists to reconstruct human experiences in a broader, more holistic context, providing a view of our ancient ancestors that includes not only what they built and produced but also how they lived, socialized, and made meaningful contributions to the world around them.

Reference: V. P. J. Arponen et al, The Capability Approach and Archaeological Interpretation of Transformations: On the Role of Philosophy for Archaeology, Open Archaeology (2024). DOI: 10.1515/opar-2024-0013

Think this is important? Spread the knowledge! Share now.