In a remarkable discovery that challenges our previous understanding of ancient embalming practices, a team of bioarchaeologists from the Austrian Archaeological Institute, Université de Bordeaux, and Aix-Marseille Université has uncovered evidence of an aristocratic family in France embalming their loved ones for nearly two centuries. The findings, published in the journal Scientific Reports, mark the first documented instance of such a practice among French elites during the early 16th to late 17th century.

The practice of embalming is not new to the study of ancient civilizations. Most notably, ancient Egypt is renowned for its advanced mummification processes, which were used to preserve the bodies of royals and high-status individuals. Similarly, evidence has surfaced of similar practices in pre-Columbian South America, where embalming played a part in religious and funerary customs. However, this new study presents an unprecedented example of embalming in France, suggesting that its practice may have had a different cultural and religious significance in Europe.

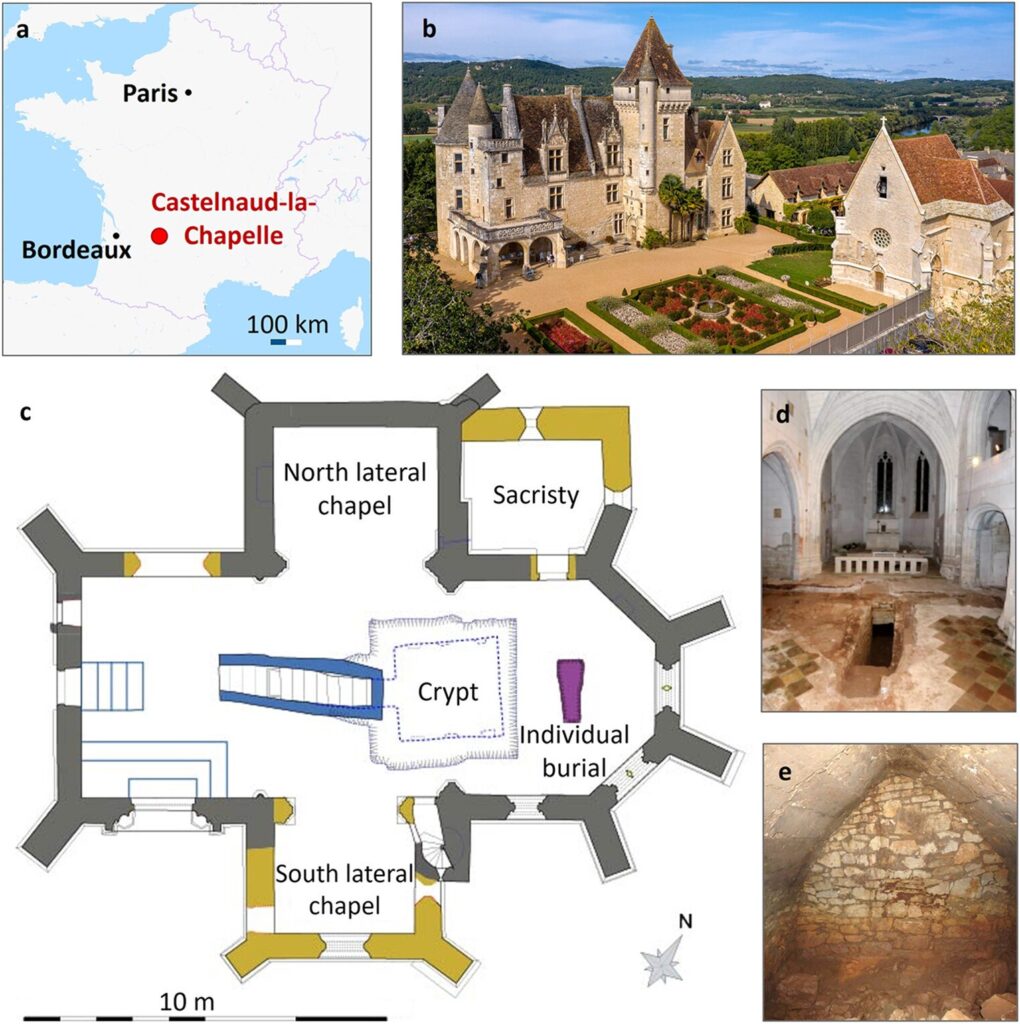

The researchers turned their attention to a series of skeletal remains found in a shared crypt used by the Caumont family at the Château des Milandes, located in southwestern France. This aristocratic family, whose lineage spanned several generations, evidently saw embalming not just as a symbolic or religious act, but as an important part of their burial rituals. The crypt revealed approximately 2,000 bone fragments belonging to 12 individuals—seven adults and five children—all of whom had been embalmed in a similar manner.

This extraordinary find offers insight into how a small but wealthy segment of French society dealt with death. The research team focused primarily on understanding the embalming techniques used, which seemed quite sophisticated and systematic. Contrary to modern methods of preservation that may involve extreme procedures to achieve long-lasting results, the goal of the Caumont family’s embalmers was different. Their approach was more focused on preparing the body for a respectful, temporary period before the burial ceremony, rather than for centuries of preservation.

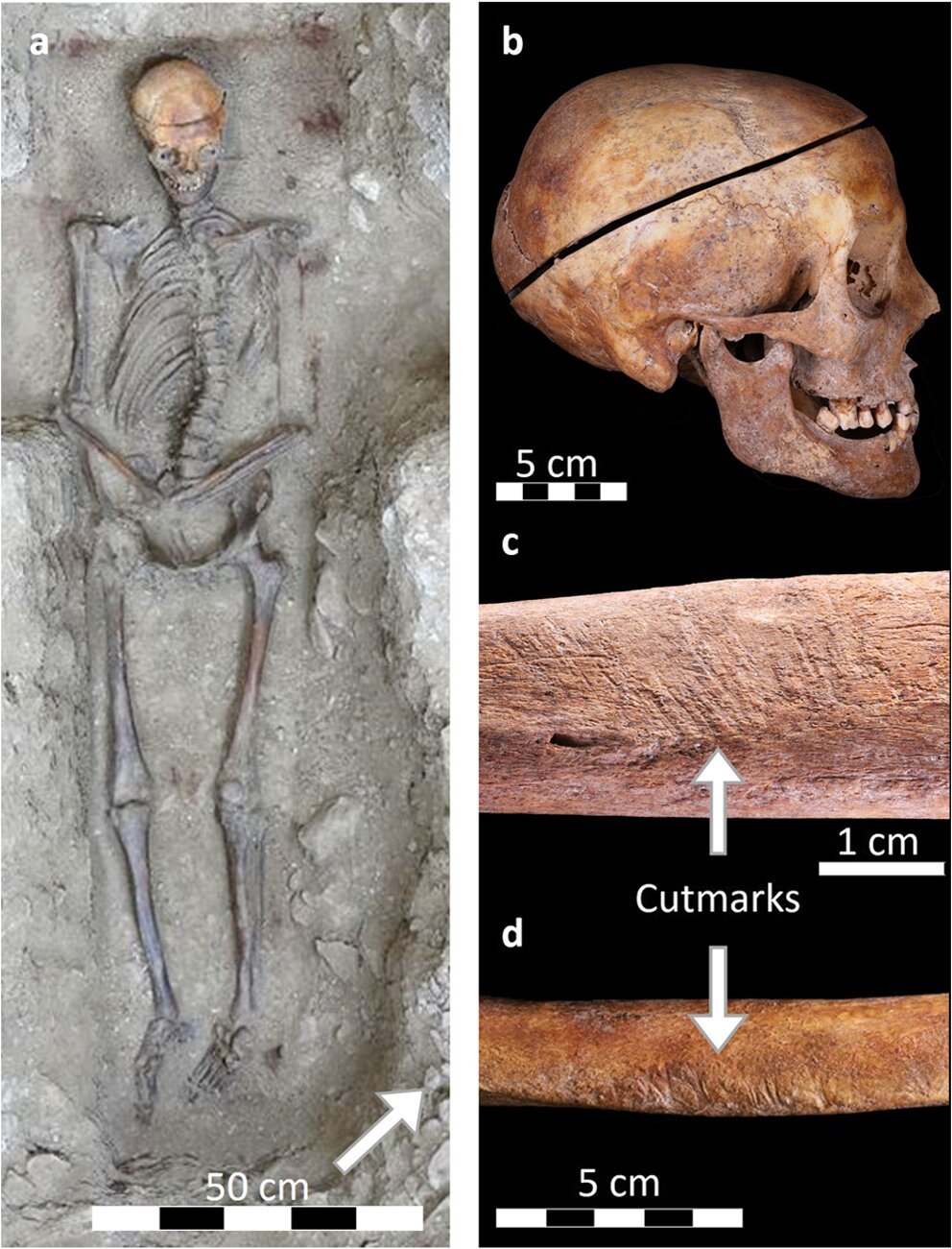

The researchers discovered that the process involved removing all internal organs from the deceased, a typical feature in many embalming techniques across cultures. What sets this discovery apart, however, is the consistent and high level of preservation. The brain was removed by carefully opening the skull—suggesting that the embalmers had advanced knowledge of anatomy and used specialized tools to carry out their work. Once the organs were removed, the body was thoroughly cleaned and washed. Then, it was filled with an embalming substance consisting of balsam and other aromatic materials, which could have served both as preservatives and a means of masking any odors during the period leading up to the funeral.

The research revealed that the embalming procedure was strikingly consistent across the bodies, regardless of age—whether the remains were of a child or an adult. This standardization in the embalming process suggests that the ritual was passed down from one generation to the next, pointing to a tradition deeply ingrained in the Caumont family’s burial customs. In fact, the embalming practices followed the descriptions detailed by Pierre Dionis, a French surgeon who published an autopsy manual in 1708. Dionis’ guidelines on the embalming process were typically used by practitioners of the time to instruct on the care of bodies following death. To find evidence of this specific technique used by the Caumont family reinforces the connection between their traditions and the broader funerary practices common during that era in France.

The familial and generational nature of the embalming also underscores the wealth and prestige of the Caumont family. Embalming, particularly at such a sophisticated level, was not a practice available to everyone. It required access to materials like balsams and aromatics, tools for surgical precision, and skilled practitioners who understood not only how to handle the human body but also the complex rituals surrounding death. This wealth likely extended to their land holdings and social influence, positioning them within the upper echelons of French society during a time of political turbulence, particularly around the reigns of French monarchs like Louis XIII and Louis XIV.

What makes this discovery especially significant is the rarity of such repeated embalming practices. Most examples of embalming practices come from scattered instances in various parts of the world, but the Caumont family’s use of it as a longstanding family tradition makes this instance truly exceptional. There is very little other evidence globally of multiple generations practicing such a ritual over the course of nearly two centuries, and this prolonged embalming ritual appears to be largely unique to the Caumont family in this particular period and region.

The researchers suggest that the long-term adherence to embalming by the Caumont family could indicate an elevated societal status, implying they were not only wealthy but maintained power and influence that was recognized through these rituals. Embalming often carried connotations of power, immortality, and reverence for the deceased, which would serve to perpetuate their family’s prestige through generations.

Moreover, the process provides an intriguing window into how the intersection of science, tradition, and cultural values can impact rituals surrounding death. During the 16th and 17th centuries, European death rituals were heavily influenced by Catholic beliefs, although burial customs varied greatly depending on one’s status in society. It is likely that the Caumont family’s embalming practices had symbolic value tied not just to preserving the body for the afterlife but also to demonstrating the family’s commitment to maintaining their legacy. Burial practices for the elite, often extravagant and meticulously arranged, were seen as symbolic of the family’s enduring power.

One element of the study that stands out is its connection to French medical history. The work of Pierre Dionis, whose instructions were evident in this embalming technique, brings attention to the growth of surgical and anatomical knowledge during the period. While Dionis’ text was primarily an instructional guide for medical professionals, it reflects broader trends in the application of medical practices to rituals surrounding death, both in hospitals and in private homes of the aristocracy.

The consistency of embalming in both children and adults, along with the sophisticated preparation methods, also raises intriguing questions about the familial beliefs surrounding death. The inclusion of children in such expensive rituals suggests that the Caumont family regarded each member—regardless of age—as integral to the continuity of the family’s legacy. In this way, embalming served as not just a means of preservation, but as a statement of family unity and identity.

This discovery opens up a variety of questions regarding the broader social context of embalming during this era in Europe. Was the practice linked to certain historical events, political upheavals, or changing perceptions of life after death? Was the ability to afford such a service a sign of an individual’s or a family’s membership in a rarefied social class, and what did embalming convey about their personal religious or philosophical beliefs about mortality?

For now, the team of researchers can confirm that this find is an extraordinary addition to the study of historical mortuary practices and gives us a rare glimpse into the funerary traditions of an elite family in 16th- and 17th-century France. The discovery serves to further our understanding of death rituals within aristocratic circles, showing not just the care and respect given to the dead but also shedding light on social hierarchies, medical advancements, and cultural values in historical France.

Reference: Caroline Partiot et al, First bioarchaeological evidence of the familial practice of embalming of infant and adult relatives in Early Modern France, Scientific Reports (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41598-024-78258-w