Archaeologists working at the biblical site of Abel Beth Maacah, located in northern Israel, have uncovered a rare boundary stone from the Tetrarchic period. This artifact, dating back to the reign of Roman Emperor Diocletian in the late third century CE, offers a glimpse into the region’s historical geography, land ownership, and the tax reforms that reshaped the Roman Empire. The discovery, which introduces two previously unknown place names, provides valuable insights into the socio-economic landscape of the Roman Near East.

The team behind this significant find includes Prof. Naama Yahalom-Mack and Dr. Nava Panitz-Cohen from the Institute of Archaeology at the Hebrew University, alongside Prof. Robert Mullins from Azusa Pacific University. Their research, published in the prestigious journal Palestine Exploration Quarterly, offers a comprehensive analysis of the boundary stone and its historical context.

Unveiling a Tetrarchic Boundary Stone

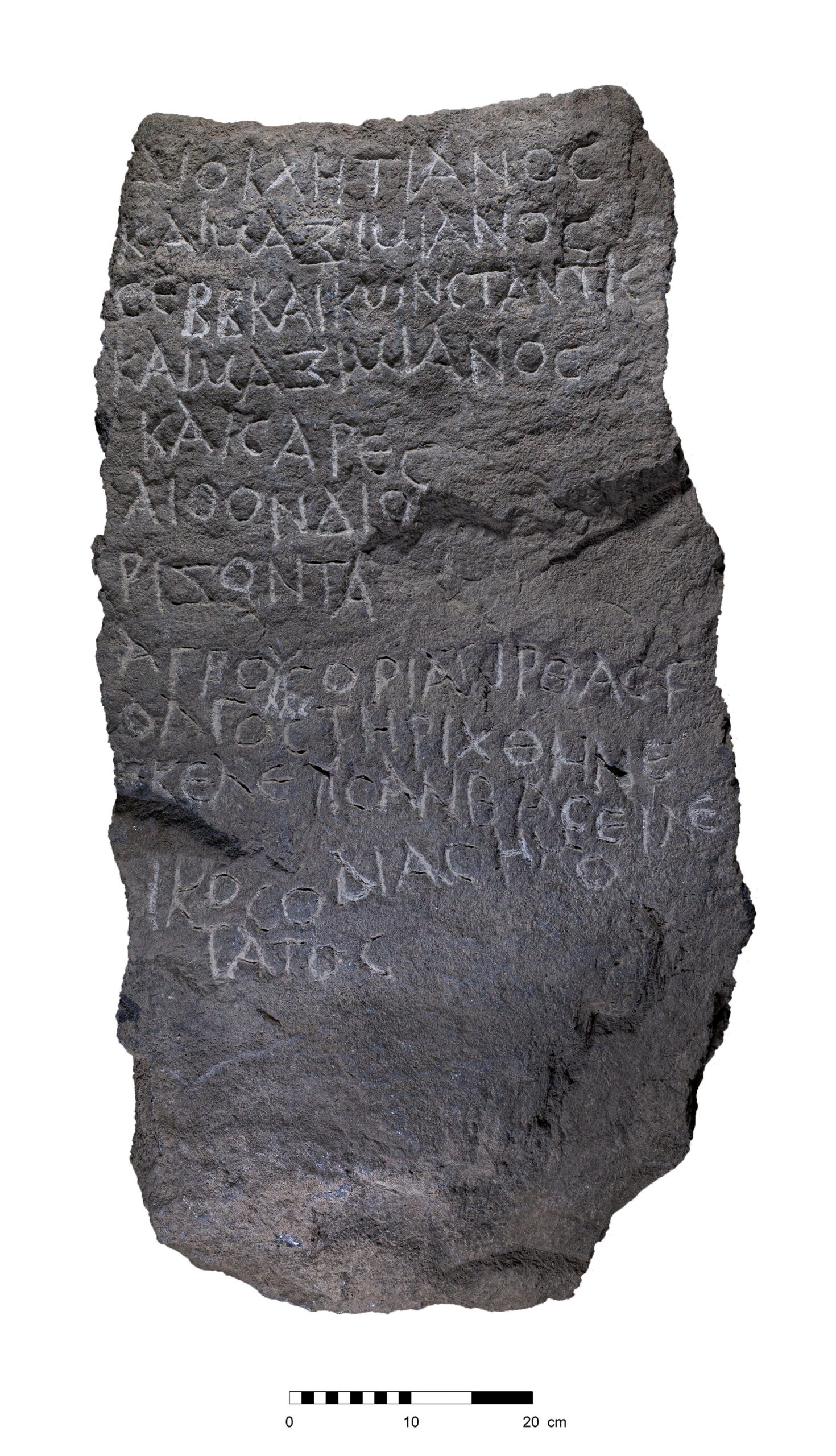

The artifact in question is a basalt slab, inscribed with a detailed Greek inscription, originally used to mark land boundaries during Diocletian’s reforms. The Tetrarchy, a system of governance instituted by Diocletian in 293 CE, divided the Roman Empire into four administrative regions, each governed by two emperors and their junior colleagues. This division was not only political but also had deep economic implications, particularly in the realm of land ownership and taxation.

The boundary stone was originally erected to demarcate agrarian borders between villages. However, it was later repurposed in the Mamluk period, several centuries after its initial use, as part of a later installation. The discovery of this stone offers a rare and direct link to the Roman Empire’s tax system and its approach to land management, providing invaluable evidence of ancient administrative practices.

New Place Names and the Imperial Surveyor

One of the most remarkable aspects of this discovery is the mention of two previously unknown villages, Tirthas and Golgol, which may correspond to ancient locations identified in the 19th-century Survey of Western Palestine. The inscription also records the name of an imperial surveyor, or “censitor,” whose identity is attested for the first time through this find. The mention of a specific imperial official underscores the central role of tax and land surveys in the Roman Empire’s efforts to manage its vast territory.

“This discovery is a testament to the meticulous administrative re-organization of the Roman Empire during the Tetrarchy,” noted Prof. Uzi Leibner, one of the lead scholars on the project. “Finding a boundary stone like this not only sheds light on ancient land ownership and taxation but also provides a tangible connection to the lives of individuals who navigated these complex systems nearly two millennia ago.”

Dr. Avner Ecker, who helped decipher the inscription, added, “What makes this find particularly exciting is the mention of two previously unknown place names and a new imperial surveyor. It underscores how even seemingly small discoveries can dramatically enhance our understanding of the socio-economic and geographic history of the region.”

A Unique Discovery in the Hula Valley

This boundary stone joins a unique corpus of over 20 similar stones found in the northern Hula Valley and surrounding areas. These stones represent a period of heightened administrative control in the region, as the Roman Empire sought to standardize taxation and clarify land ownership. The concentration of such boundary stones in this area suggests that the region was home to a significant number of small landholders, who often operated independently of larger urban centers.

The abundance of these boundary stones is not merely an indication of territorial markers; it reflects a larger trend of state-driven efforts to control the economy and manage agricultural production. The stones served as tools for maintaining order in an empire that spanned vast distances, enabling officials to delineate and regulate landholdings, enforce tax policies, and ensure that imperial decrees were followed.

The Impact of Diocletian’s Tax Reforms

The historical context of the boundary stone is deeply tied to Diocletian’s reforms, which sought to address the Roman Empire’s fiscal challenges. Diocletian’s reign marked a period of significant reorganization, and his tax reforms were aimed at stabilizing the empire’s finances. These reforms were particularly focused on land and agriculture, as the Roman Empire’s economy relied heavily on agrarian production.

Diocletian’s reforms introduced new systems of taxation that relied on precise land surveys to ensure fairness and consistency. The presence of this boundary stone, marking agrarian borders between villages, reflects the Roman emphasis on controlling and regulating land use as part of this broader fiscal reorganization. Such stones were crucial for enforcing tax policies, as they clearly defined property boundaries, reducing disputes and ensuring that the empire could collect taxes more effectively.

Interestingly, contemporaneous rabbinic traditions mention the burden imposed by Diocletian’s reforms, particularly in the northern part of the empire, and hint at the hardships these reforms brought to local populations. The tax burdens may have placed a strain on rural communities, as small landholders had to comply with increasingly complex regulations and levies.

Insights into Local Settlement Patterns and Socio-Economic Dynamics

The discovery of the boundary stone provides a rich source of information about local settlement patterns during the Tetrarchic period. The inscription, with its reference to imperial surveyors and land boundaries, offers a snapshot of how land was distributed and controlled in this rural region. It also highlights the relationship between the Roman state and local communities, emphasizing the top-down nature of imperial governance.

The fact that the boundary stone was found in secondary use in a Mamluk-period installation further enriches our understanding of the site’s long-term significance. It suggests that the region remained important throughout the centuries, with later civilizations repurposing Roman-era artifacts for their own needs. This continuity of settlement underscores the enduring legacy of the Roman administrative system in the region, even after the fall of the empire.

Additionally, the mention of previously unknown villages expands our understanding of the region’s historical geography. These place names, Tirthas and Golgol, may correspond to sites that were significant during the Roman period but were not previously identified in modern research. The discovery of these names opens up new avenues for archaeological exploration and historical research in the northern Hula Valley and surrounding areas.

Conclusion: Connecting the Past to the Present

The discovery of this Tetrarchic boundary stone at Abel Beth Maacah provides a unique window into the administrative practices of the Roman Empire during the late third century CE. It illuminates the role of land ownership and taxation in shaping the socio-economic landscape of the Roman Near East, offering valuable insights into the lives of ordinary people navigating an increasingly complex imperial system.

By uncovering two previously unknown place names and documenting the work of an imperial surveyor, the discovery enhances our understanding of the region’s historical geography. It also enriches our knowledge of the broader impact of Diocletian’s tax reforms on rural communities and the Roman Empire’s efforts to assert control over its territories.

As archaeologists continue to study the find and its implications, it is clear that this discovery is not just an isolated artifact but a key to unlocking the ancient world’s administrative and socio-economic structures. By connecting the past to the present, it brings us one step closer to understanding the intricate workings of an empire that spanned continents and influenced the course of history for centuries to come.

Reference: Avner Ecker et al, ‘Diocletian oppressed the inhabitants of Paneas’ (ySheb. 9:2): A New Tetrarchic boundary stone from Abel Beth Maacah, DOI: 10.1080/00310328.2024.2435218