Franchthi Cave, one of Greece’s most important prehistoric sites, offers a remarkable glimpse into human history spanning nearly 40,000 years. Located on the Bay of Koilada in the Peloponnese region, the cave is not only an archaeological treasure but also a subject of intense research. A recent isotope study conducted by Simon Fraser University, the Greek Ministry of Culture, and the University of Bologna has provided new insights into the dietary patterns of Mesolithic and Neolithic humans at this site. The findings challenge earlier assumptions about the reliance on marine resources, revealing a predominantly terrestrial-based diet for these ancient peoples.

The Significance of Franchthi Cave

Franchthi Cave is not just a strategic location, but a deeply significant archaeological site, renowned for providing a continuous cultural record from the Upper Paleolithic through to the Neolithic period. It has been extensively excavated, primarily between 1967 and 1979, and offers a wealth of material from both the Mesolithic (12,000–8,500 BCE) and Neolithic (8,500–3,000 BCE) periods. The cave’s importance is rooted in its occupation over millennia, capturing profound changes in human behavior, culture, and economy.

The Bay of Koilada, which lies directly in front of the cave, was a critical area for the site’s inhabitants, but its significance to the diet of its occupants has long been debated. Archaeological evidence shows substantial marine remains, including fish and shellfish, which would suggest a connection between the cave dwellers and nearby aquatic resources. However, earlier isotope studies from Franchthi had indicated only minimal reliance on marine foods, especially during the Mesolithic period. This was an observation that had puzzled scholars, given the site’s location near the sea.

Bridging the Gap: High-Resolution Isotope Analysis

To build on earlier findings, researchers undertook a high-resolution isotope dietary study to investigate the nutritional habits of Franchthi’s ancient populations, focusing specifically on human remains and those of contemporary animals. In particular, the new research used compound-specific isotope analysis, a more advanced technique than traditional bulk isotope studies. This method involves analyzing individual amino acids from bone collagen, offering more detailed and precise insights into dietary habits than previous approaches.

The study, titled High-resolution isotope dietary analysis of Mesolithic and Neolithic humans from Franchthi Cave, Greece, was published in the scientific journal PLOS ONE and provides novel insights into ancient dietary practices. By examining isotopic data from the bones of five humans and six animals, the research team sought to determine the proportion of marine versus terrestrial sources in the diet during two key periods of the cave’s occupation: the Lower Mesolithic (c. 8700–8300 BCE) and the Middle Neolithic (c. 6600–5800 BCE).

Methodology: Isotope Analysis and Radiocarbon Dating

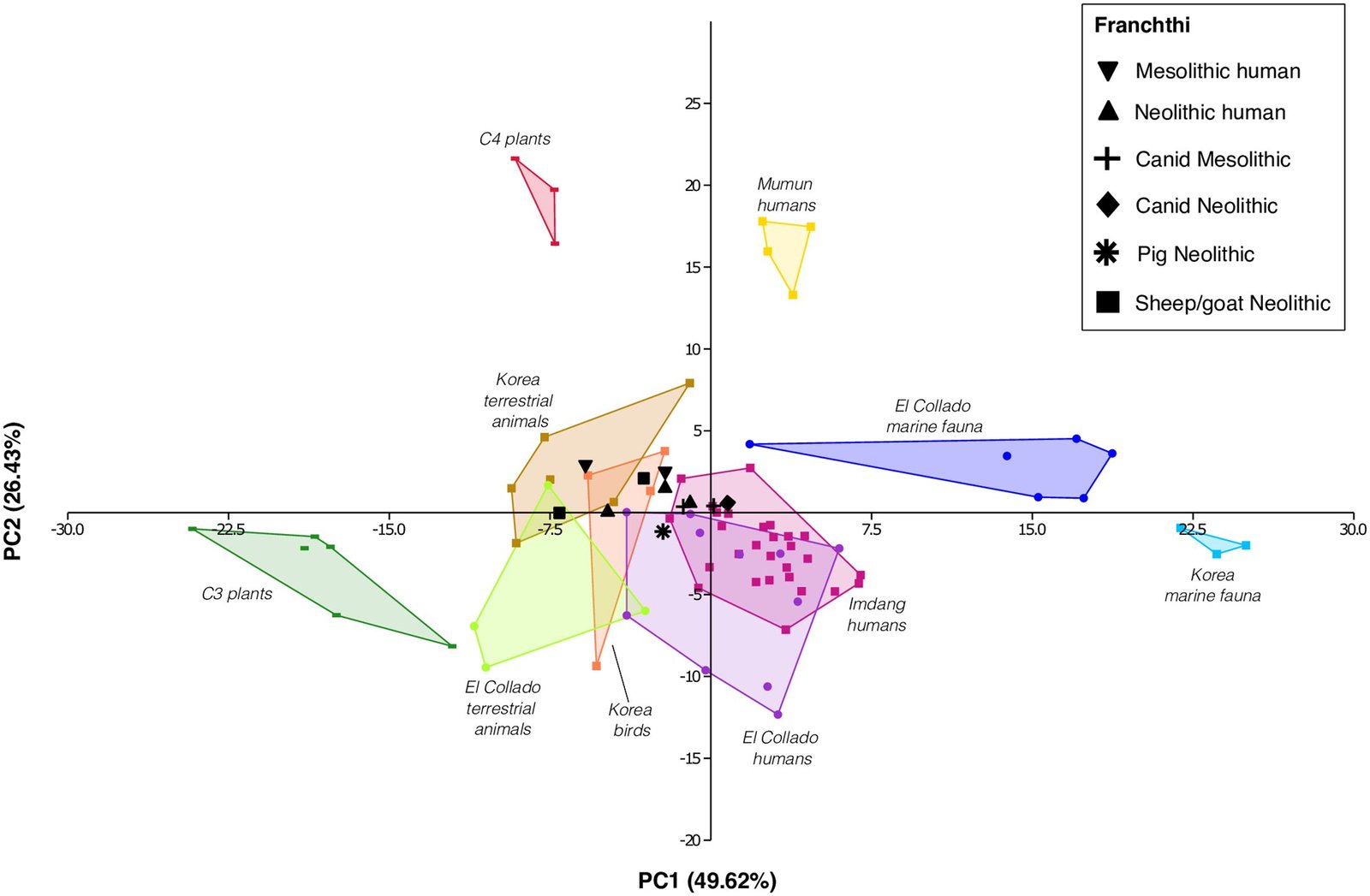

The research employed two primary isotopic approaches: carbon-13 (δ13C) and nitrogen-15 (δ15N) stable isotope analysis. These two isotopes are particularly useful in reconstructing diet. The carbon isotope helps distinguish between plant types (C3 plants, which dominate temperate climates, and C4 plants, often associated with hot, dry conditions), while the nitrogen isotope indicates the trophic level (how high up an animal is in the food chain) and, by extension, whether the diet is plant-based or reliant on animal protein.

Collagen extracted from human and animal bones served as the primary medium for isotope analysis, providing a tangible record of diet. The bones examined came from two Lower Mesolithic individuals (from the period c. 8700–8500 BCE) and three Middle Neolithic individuals (6600–5800 BCE). The analysis included the extraction of collagen, which was then studied through accelerator mass spectrometry and combined with radiocarbon dating to accurately date the samples.

Isotopic data from the amino acids provided the nuanced dietary details that indicated the prominence of terrestrial animal proteins and low reliance on marine food sources. This was in stark contrast to initial expectations that proximity to the coast would have encouraged frequent consumption of fish and seafood.

Key Findings of the Study

Terrestrial Diet with Minimal Marine Inputs

One of the most significant findings from this research was the confirmation that the human populations at Franchthi Cave, during both the Mesolithic and Neolithic, relied predominantly on terrestrial animal protein. Isotopic signatures from both periods showed that the majority of the protein consumption was from land-based animals such as wild mammals, particularly those hunted or domesticated later on, like sheep. Contrary to the assumption that coastal populations might consume substantial marine resources, the data revealed that Franchthi Cave inhabitants consumed little to no marine foods.

This discovery challenges the notion that proximity to the sea would lead to a reliance on marine animals. Instead, the results strongly suggest that terrestrial resources were a more reliable and prevalent dietary source throughout these periods. Isotope ratios for carbon-13 and nitrogen-15 reflected this, indicating consumption of land-based animals over marine food sources.

The study also highlighted an important shift in diet between the Mesolithic and Neolithic. The Lower Mesolithic individuals, who were earlier in the occupation timeline, showed higher nitrogen-15 values, which is characteristic of diets rich in animal protein. This suggested that the people had a primarily meat-based diet. By contrast, the Middle Neolithic individuals exhibited slightly more dietary variation, likely due to the introduction of farming and herding practices.

Amino Acid Proxies for Trophic Level

Another innovative aspect of the study was the use of amino acid-specific proxies to refine the analysis. Essential amino acids like phenylalanine (Phe) and valine (Val) helped identify those who relied on terrestrial C3 plants, confirming that humans at Franchthi Cave were not only consuming high levels of animal protein but also participating in the complex food chains dependent on plant-based nutrients. By comparing these proxies with isotopic shifts in nitrogen-15, the team was able to further delineate the specific sources of protein in their diet, reinforcing the idea that Franchthi’s inhabitants had a deeply terrestrial dietary base.

Animal Remains: A Closer Look at Domesticated Species

The remains of animals excavated at Franchthi Cave also revealed interesting dietary interactions. Neolithic sheep, for instance, showed elevated nitrogen-15 levels, suggesting these animals grazed on nitrogen-enriched vegetation in coastal areas. This finding points to a deeper integration of domestic livestock into the Franchthi people’s food production and consumption practices. Other animals like pigs and canids exhibited omnivorous diets, likely fed by scraps from human settlements.

This correlation suggests that while humans at Franchthi consumed limited marine resources, their animals—especially those domesticated for farming or herding—were significantly connected to the coastal environment, grazing on coastal vegetation. This further bolsters the theory that the environment played a role in shaping diet, even if that influence did not translate into heavy seafood consumption.

The Enigma of Marine Resources

Despite the wealth of archaeological evidence showing marine shells and fish bones at Franchthi Cave, the isotopic study underscores a more complex interaction with the sea. Shallow-water fish and sea shells were indeed present, but their contribution to the diet of Franchthi’s inhabitants was not significant enough to alter the isotopic signatures we would expect from regular or intensive marine consumption.

This paradox might be explained by changes in sea levels over time. Earlier studies indicate that during the Lower Mesolithic, Franchthi Cave was located as much as 2 kilometers from the coastline, challenging the assumption that marine resources would have been easily accessible. A 2018 study, Flooding a landscape: Impact of Holocene transgression on coastal sedimentology and underwater archaeology in Kiladha Bay, Greece, confirmed that rising sea levels over time pushed the shoreline farther from the cave. Consequently, during the Mesolithic, the bay area near the cave was not as conducive to regular harvesting of marine resources, which explains the minimal evidence of marine consumption in the isotopic data.

Conclusion: Revising Our Understanding of Prehistoric Diets

The new isotope study at Franchthi Cave offers critical insights into the dietary patterns of prehistoric populations. It reveals that, despite the proximity to the sea, terrestrial diets dominated during both the Mesolithic and Neolithic periods. This study also underscores the complexities involved in understanding prehistoric diets and emphasizes that access to certain resources did not necessarily dictate their consumption.

These findings suggest that agriculture, the domestication of animals, and shifts in coastal geography influenced the human diet, and such dietary practices were far more varied and nuanced than originally assumed. Future studies, particularly those examining older or other layers at Franchthi, could further enrich our understanding of how marine resources were utilized throughout the entire occupation history of the site.

Through continued isotope analysis and archaeological excavation, we gain not only a richer picture of ancient diets but also a better understanding of human adaptation in diverse environmental settings across prehistoric Europe.

Reference: Valentina Martinoia et al, High-resolution isotope dietary analysis of Mesolithic and Neolithic humans from Franchthi Cave, Greece, PLOS ONE (2025). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0310834

Think this is important? Spread the knowledge! Share now.