Research conducted by the Department of Sociology & Anthropology at Ohio University has yielded remarkable findings from a fossil site in Grăunceanu, Romania, pushing back the known presence of hominins in Europe by nearly half a million years. This discovery, which dates to at least 1.95 million years ago, places Grăunceanu as the oldest confirmed European evidence of hominin activity. The research, published in the journal Nature Communications, represents a major contribution to the ongoing debate about the timing and extent of hominin dispersals into Eurasia, revealing evidence of ancient human ancestors in a region where fossil findings had previously suggested later arrivals.

New Insights into Early Hominin Activity in Europe

The Grăunceanu site is part of the Tetoiu Formation in Romania, situated in the Olteţ River Valley in East-Central Europe. This area, part of the Late Villafranchian biochronological zone (2.2–1.9 million years ago), has yielded a wealth of faunal remains that depict a forest-steppe environment—a mosaic of woodlands and grasslands. These environmental conditions contrast with what is often envisioned for the earliest sites of human dispersals, which have generally been assumed to be located in areas with more open, less seasonal climates, such as Georgia or western Asia.

Up until this discovery, European hominin evidence older than 1.4 million years ago was sparse and mainly confined to controversial sites lacking reliable dating and clear indicators of hominin behavior. This study alters the historical landscape of human evolution, offering a direct glimpse at hominin activity in Europe as early as 1.95 million years ago, demonstrating a much earlier presence on the continent than previously established.

Analyzing the Evidence from Grăunceanu

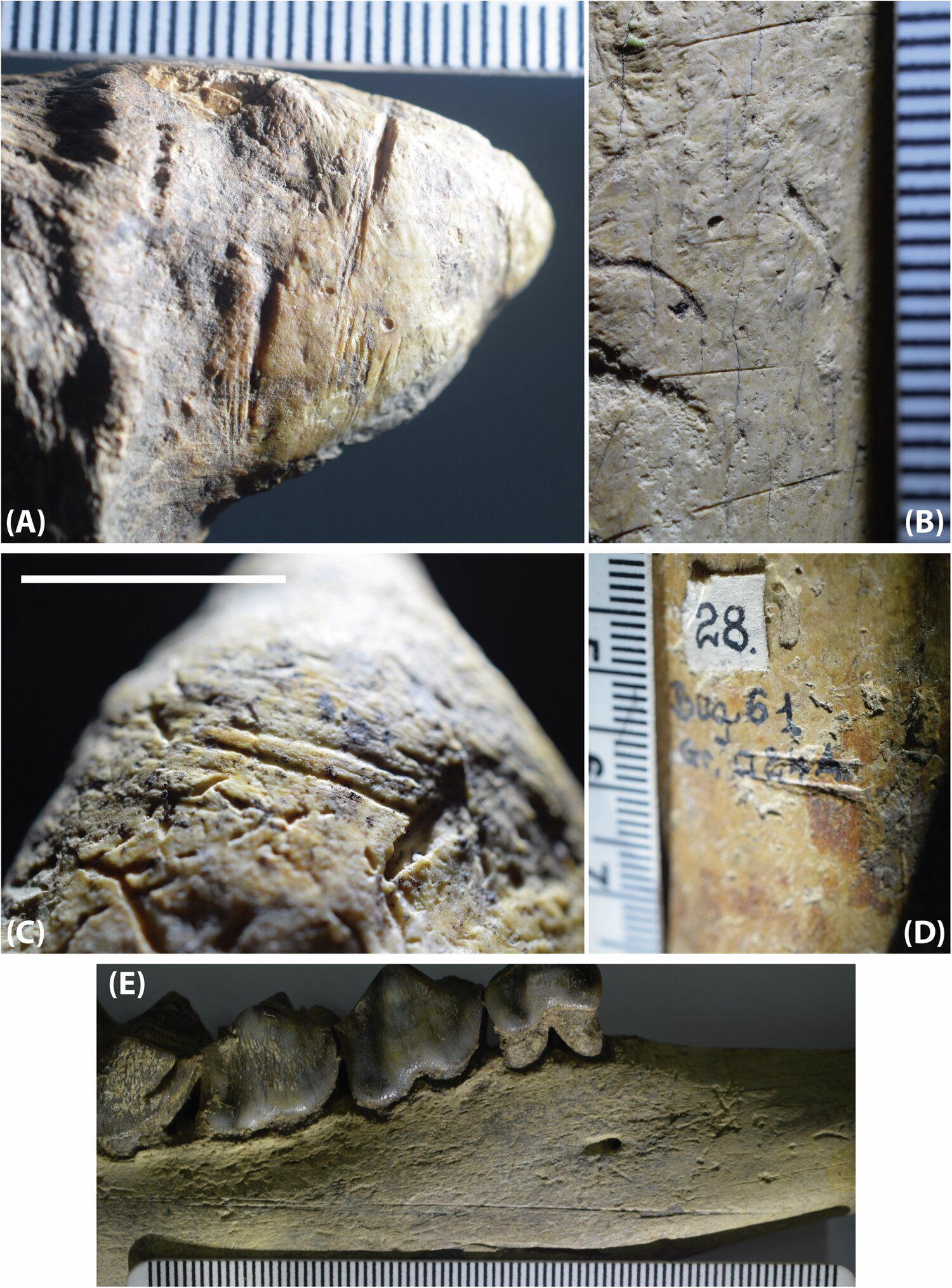

The breakthrough in understanding the early presence of hominins in Europe stems from careful analysis of faunal remains from Grăunceanu. The team scrutinized a total of 4,524 specimens of bones and teeth, searching for surface modifications that might indicate human activity. Over the course of their study, the researchers identified twenty bones with anthropogenic modifications. Seven of these showed strong evidence of cut marks, demonstrating signs of deliberate hominin butchery, which aligns with methods of animal processing observed in later hominin archaeological sites.

The marked bones—including animal tibiae and mandibles—show linear, straight, transverse marks consistent with defleshing techniques. These cut marks reflect purposeful action, indicating that the hominins at Grăunceanu were utilizing tools to remove meat from bones. These modifications were distinguished from other types of damage, such as those caused by carnivore teeth or trampling, thanks to high-precision 3D optical profilometry and quantitative analysis of the marks. The clear anthropogenic nature of the marks provides the first reliable proof of hominin activity in Europe older than 1.4 million years.

The presence of cut marks on such diverse animal remains is crucial. It is highly suggestive of hominin activities such as butchering, which is traditionally linked to an emerging culture of tool use and food processing—key milestones in human evolution. This insight into Grăunceanu provides early evidence for an expanding hominin presence across Europe.

Dating the Grăunceanu Fossils

The key to establishing the antiquity of the site lies in its robust age determination. The researchers turned to an advanced technique known as laser ablation U-Pb dating, which is applied to measure dentine samples found at Grăunceanu and nearby fossil sites. This precision method provided accurate minimum depositional ages for the fossil material, yielding dates between 2.01 ± 0.20 million years and 1.87 ± 0.16 million years. The findings show an average age of approximately 1.95 million years, firmly anchoring the site within the Pleistocene epoch, well over a million years before hominin activity had previously been recorded in Europe.

These age results are further validated by comparisons with previous faunal-based biochronological estimates, corroborating the notion that Grăunceanu represents a genuine early hominin site in Europe. The age range places it among some of the most ancient sites for early hominins in Eurasia, giving it a unique place in understanding the spread of humanity across the globe.

Environmental Context of Early Hominin Dispersals

The study does not only focus on the hominin activity itself but also provides significant information about the environmental conditions in which these early humans lived. By analyzing isotope ratios from a horse molar recovered at Grăunceanu, the researchers were able to reconstruct seasonal temperature and precipitation patterns of the time. This analysis reveals that the site was situated in a temperate woodland-grassland environment, not dissimilar to modern savannas, and likely benefited from higher-than-present seasonal rainfall.

Such conditions likely made the area habitable for diverse forms of life, including animals like ostriches, pangolins, and even an extinct European monkey—species typically associated with more temperate climates. Interestingly, this animal assemblage suggests that although the site lay in a mid-latitude region, it would have experienced mild winters—further evidence of a relatively benign climate during periods of the early Pleistocene.

Understanding the climatic conditions in which early hominins lived offers insight into their migratory patterns and ecological adaptability. The warmer environment, with abundant plant and animal resources, may have played a critical role in enabling these early humans to venture beyond Africa during interglacial periods, when conditions were likely more favorable. The interglacial climate would have seen temperate periods between ice ages, allowing for the exploitation of new and diverse environments.

Implications for Early Hominin Migration and Dispersals

The findings from Grăunceanu serve as a stark challenge to the previously held notion that Georgia—and more specifically the Dmanisi site—represented the earliest indisputable evidence of hominin dispersals out of Africa, around 1.85–1.77 million years ago. Until now, it had been generally assumed that hominins only began to venture into Eurasia around this time. Grăunceanu’s age of 1.95 million years clearly pushes back these early migrations, indicating that hominins may have begun dispersing across Europe and into other parts of Eurasia at a much earlier date than previously believed.

Moreover, the evidence of hominin butchery and exploitation of temperate environments, including the analysis of faunal remains and isotopic data, suggests that the early migrants were adaptable, capable of thriving in diverse ecosystems. They may have moved not only in response to the availability of food but also to exploit more favorable seasonal conditions during particular times in the early Pleistocene.

Thus, this discovery supports a new hypothesis that hominins might have dispersed into regions like South-Eastern Europe via a broad network of interglacial corridors, allowing them to move more freely across Eurasia and establish themselves in varied climates long before the population reached locations like the Caucasus or the steppes of Central Asia.

Conclusion: Rewriting Human Evolution History

The findings from Grăunceanu significantly reshape our understanding of human evolution. Prior to this study, evidence for early European hominin activity was sparse, and many questions remained about the timing and routes of human migrations from Africa. The discovery of hominin activity at Grăunceanu, dating back nearly 1.95 million years ago, revises previous models of human dispersal, suggesting that hominins spread into Europe much earlier and across a far broader ecological spectrum than previously understood.

Through careful analysis of fossils, bone modifications, and environmental factors, researchers have demonstrated that early hominins were ecologically flexible, capable of adapting to diverse climates, and possibly moved along migratory corridors when environmental conditions supported these longer-range dispersals. This not only opens new chapters in understanding human migrations but underscores the adaptability and resourcefulness of our ancient ancestors, continuing to shape the course of human evolution. As these studies deepen and additional discoveries emerge from regions like Grăunceanu, humanity’s migration story will only become more detailed and complex, offering a fuller understanding of where we come from and how we populated the continents we now call home.

Reference: Sabrina C. Curran et al, Hominin presence in Eurasia by at least 1.95 million years ago, Nature Communications (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-56154-9