Sepsis, one of the most common and deadly conditions globally, kills approximately 11 million people annually according to the World Health Organization (WHO). It’s characterized by out-of-control inflammation, often triggered by an infection, which can lead to shock, organ failure, and eventually death if not treated swiftly and effectively. Yet, recent research has shown that the root cause of the deadly inflammation in sepsis may not be the infection itself, but rather the response of the body’s own cells. A study from the UConn School of Medicine, published on January 23 in the journal Cell, sheds new light on the cellular mechanisms behind this phenomenon and offers a potential path forward for new therapies.

The Puzzle of Sepsis

Sepsis has long been thought of as a reaction to the bacteria, viruses, or fungi that invade the body. While infection certainly plays a critical role in triggering sepsis, researchers are now discovering that it’s not the microbes themselves that drive the runaway inflammation. Rather, the body’s own cells, which are caught up in the response to the infection, may be playing a more lethal role. These cells, whether infected or not, begin to die in a process known as programmed cell death, or pyroptosis. As they die, they don’t simply disappear; they send out signals that seem to affect neighboring cells, essentially passing on the “death sentence” to them. This cycle continues and amplifies the inflammation, escalating the condition until it spirals out of control.

Understanding what causes these cells to send such “lethal messages” could provide a way to intervene in sepsis, stopping the deadly cascade before it’s too late. In their recent study, Vijay Rathinam and his colleagues at the UConn School of Medicine uncovered a crucial piece of this puzzle, revealing that the signals cells send to each other are not intentional but rather a byproduct of the cells trying to save themselves from the infection.

The Mechanism Behind the Death Message

To understand the key mechanism at play, it’s necessary to first explore how a cell normally deals with infection. When a cell becomes infected with a pathogen, it tries to protect the body by self-destructing in a controlled manner, which is known as cellular apoptosis or programmed cell death. In sepsis, however, a different process takes place: pyroptosis. This form of cell death is often triggered by infection and involves a unique and aggressive pathway. Pyroptosis is characterized by the activation of gasdermin-D, a protein that plays a key role in creating holes in the cell’s membrane.

Gasdermin-D is usually activated when a cell senses an infection, leading to its self-destruction. The protein is transported to the cell surface, where it assembles into a pore-like structure, which punctures the cell membrane. This rupture causes the contents of the cell to spill out, causing the cell to collapse and die. The loss of cellular integrity and the release of intracellular contents trigger an inflammatory response that helps to combat the infection.

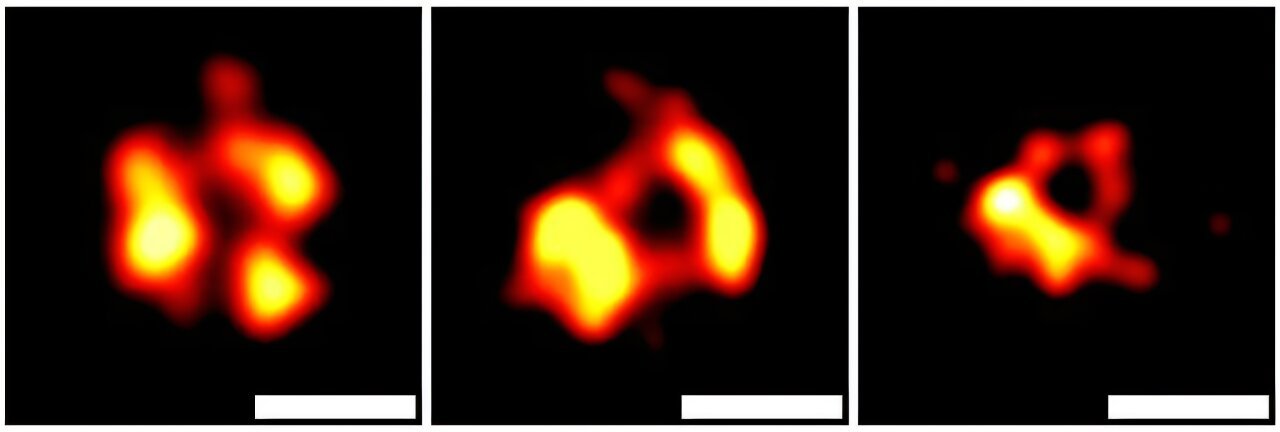

However, this is not the end of the story. Rathinam and his team discovered that, under certain circumstances, cells don’t always die immediately after forming the gasdermin-D pore. Sometimes, the cell can eject a portion of its membrane, which contains the activated gasdermin-D pores, into the surrounding environment. This process forms a vesicle — a small, bubble-like structure that contains the lethal gasdermin-D.

Interestingly, the vesicle doesn’t just float aimlessly; it can travel to nearby cells, where it attaches to the cell membrane and punches another gasdermin-D pore into the healthy cell. This causes the neighboring cell to also rupture, spill its contents, and eventually die, perpetuating the cycle of cell death and inflammation.

How the Death Spiral Fuels Sepsis

The critical insight from Rathinam’s research is that this process of vesicle release and the spreading of gasdermin-D pores is not a deliberate action by the dying cell, but rather a side effect of the cell’s survival attempt. Essentially, cells are trying to protect themselves from the infection, but in the process, they inadvertently spread death to surrounding cells, which exacerbates the inflammatory response.

This cascading effect, in which one cell’s attempt at survival becomes the death sentence for many others, amplifies the damage caused by sepsis. A group of dying cells can release enough of these gasdermin-D vesicles to overwhelm surrounding tissue, further fueling the out-of-control inflammation that characterizes sepsis.

The researchers argue that understanding how these vesicles spread and how they function in this deadly feedback loop may provide the key to stopping sepsis in its tracks. If scientists can find a way to prevent the release of gasdermin-D vesicles or block the destructive effect of these vesicles on surrounding cells, it could offer a new therapeutic approach for treating sepsis and similar inflammatory diseases.

Towards a New Treatment for Sepsis

The goal of Rathinam’s research is to identify ways to disrupt the release or the action of these gasdermin-D vesicles, potentially halting the progression of sepsis before it becomes fatal. While this approach is still in the early stages, the findings open up exciting possibilities for treating sepsis more effectively and saving lives.

By targeting the gasdermin-D vesicles or the pathways that regulate their release, researchers could develop drugs that block the spread of the deadly message from one cell to the next. This would prevent the vicious cycle of cell death and inflammation, allowing the body to recover from sepsis or other severe inflammatory conditions more quickly and with less harm.

In addition to sepsis, this discovery may also have implications for other diseases involving uncontrolled cell death and inflammation, such as autoimmune diseases and neurodegenerative disorders, where excessive cell death contributes to disease progression.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the discovery of how dying cells propagate lethal messages through gasdermin-D vesicles offers a groundbreaking understanding of the mechanisms behind sepsis. Rather than being solely driven by the infection itself, the runaway inflammation seen in sepsis may be fueled by the spread of these deadly vesicles from one cell to another. This insight could pave the way for new therapeutic approaches aimed at disrupting the cycle of cell death and inflammation, providing hope for more effective treatments for sepsis and other inflammatory diseases. While the research is still in its early stages, the potential to target these vesicles and prevent their damaging effects holds great promise. As scientists like Vijay Rathinam and his team continue their work, these findings could one day revolutionize how we treat sepsis, offering better outcomes and ultimately saving lives from one of the world’s most deadly conditions.

Reference: Skylar S. Wright et al, Transplantation of gasdermin pores by extracellular vesicles propagates pyroptosis to bystander cells, Cell (2024). DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2024.11.018