Atoms and light interact in intricate and often unpredictable ways, affecting the physical world at both macroscopic and microscopic scales. These interactions lie at the heart of quantum mechanics and present a primary challenge for the development of quantum technologies such as quantum computing, secure communications, and precision measurement. Understanding how atoms and light communicate with each other, and how these interactions can be controlled, is essential for pushing the boundaries of modern physics and realizing these advanced technological applications.

Basics of Light-Atom Interactions and Quantum Entanglement

The behavior of atoms when influenced by light can often be modeled using a simplified two-level system, which consists of a ground state and an excited state. Under such a system, atoms can be excited from the ground state to the excited state by absorbing photons, and conversely, they can relax back to the ground state by emitting a photon. In a typical arrangement of atoms, such as in a crystal lattice, when one atom emits a photon, the photon might not just escape into the surroundings. Instead, it can be absorbed by a neighboring atom in its ground state, causing that atom to become excited as well. This interaction between nearby atoms, facilitated by the exchange of photons, is often referred to as dipole-dipole interaction.

In this simplified picture, atoms interact with their neighbors even when they don’t directly collide. This principle is crucial for creating and maintaining quantum entanglement across a collection of atoms, even when they cannot physically “bump” into one another. However, the dynamics behind the interaction between multiple atoms becomes significantly more complex when these interactions start influencing the states of large systems of atoms.

“While the underlying idea of atom-light interaction seems straightforward, when you involve multiple atoms interacting through multiple photon exchanges, the situation quickly becomes much more complicated,” said Ana Maria Rey, a Fellow at JILA and NIST, as well as a professor at the University of Colorado Boulder.

As the interaction between atoms grows more complex, tracking the state of individual atoms becomes infeasible due to computational constraints. Further complicating the situation is the fact that once atoms interact with one another, they can become entangled, meaning their states become correlated in ways that make them act as a unified whole rather than a collection of independent particles. This entanglement, which is essential for most applications in quantum technology, disappears when the system returns to its ground state, thus presenting a significant challenge in understanding and harnessing these phenomena.

The Role of Multi-Level Systems

In classical physics, the state of an atom was often modeled using just two energy levels: a ground state and a single excited state. However, in the realm of quantum mechanics, atoms can possess many more internal states. When more than two states come into play, especially in higher-level systems where transitions can occur between different excited states or metastable levels, the interactions between multiple atoms become much more complex. Understanding these interactions becomes a multifaceted problem, one that has so far remained an elusive target for both theorists and experimentalists.

In systems with only two atomic levels, the interactions are relatively simple to track, and when only a small number of atoms are involved, solving for the dynamics of their states is numerically feasible. However, this simple description does not capture the rich complexity that arises when additional atomic levels are included. Introducing just a single additional energy level allows for exponentially more configurations, making the system more complex. From the perspective of quantum technologies, these systems become much more valuable due to their potential to create more robust entanglement without requiring a constant external influence to maintain the states.

However, such multi-level atomic systems present major challenges in computation. As Rey explains, understanding the behavior of these complex atom-light interactions, especially as they pertain to multi-level systems, can be prohibitively difficult with the current computational methods available.

A New Study on Atom-Light Interactions

Recently, Ana Maria Rey, James K. Thompson (both of JILA and NIST), Sanaa Agarwal, and Asier Piñeiro Orioli from the University of Strasbourg, took a significant step forward in studying atom-light interactions in the context of multi-level atomic systems. Their recent research, published in Physical Review Letters, delves into atom-light interactions involving effective four-level atoms. These atoms contain two ground states and two excited states, offering a far more nuanced view of quantum interactions.

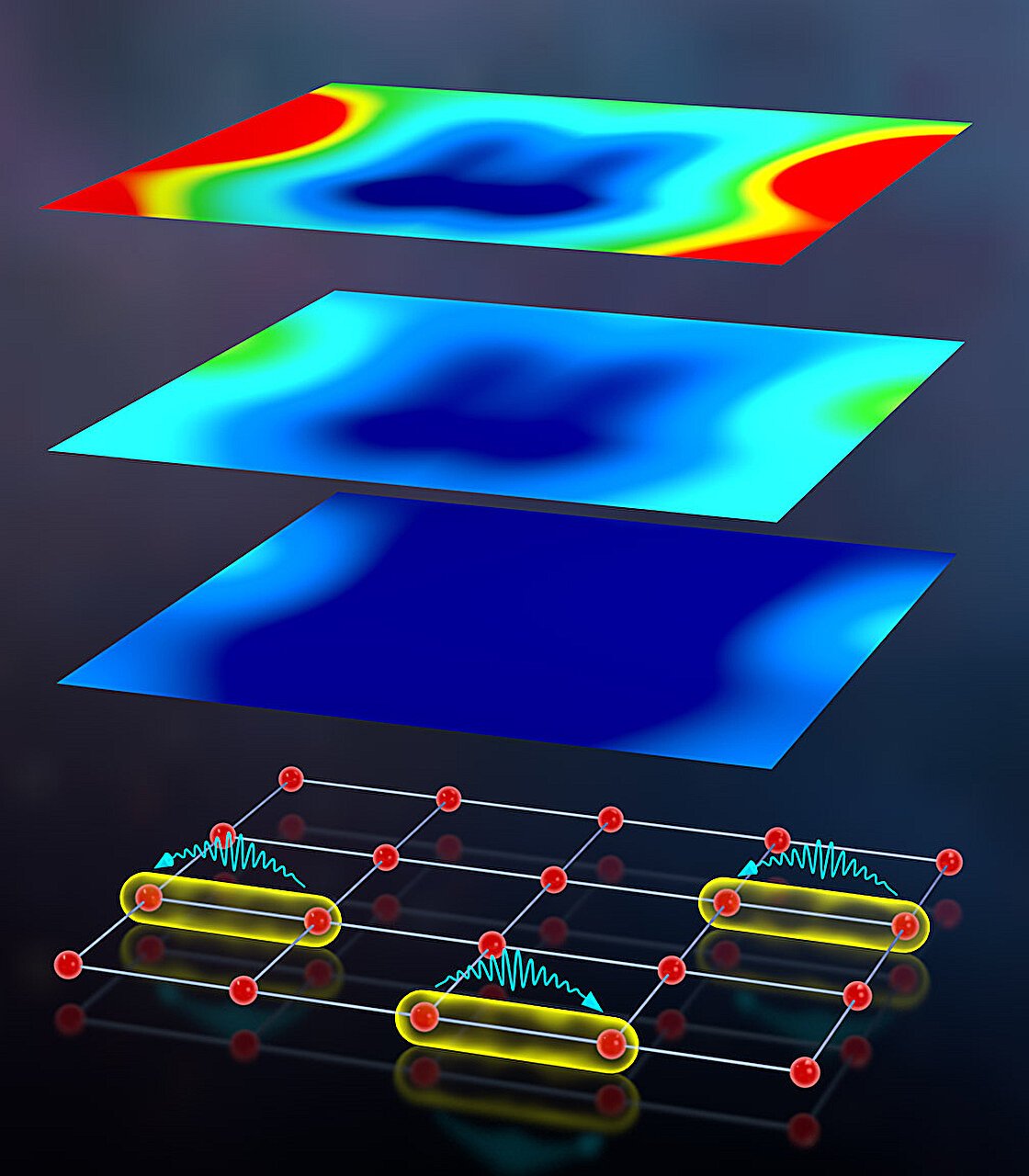

“We know that including the full multilevel structure of atoms can give us richer physics and new phenomena, which are promising for entangled state generation,” said Agarwal, the lead author of the study. The team studied this system by using strontium atoms arranged in either one-dimensional or two-dimensional crystal lattices.

By isolating four internal energy levels in the atoms and focusing on metastable atomic states—states in which atoms can remain for extended periods of time before transitioning—this team was able to study the interaction dynamics in ways that had never been fully explored before. These metastable states have much smaller energy separations than typical optical transitions, which allows the researchers to manipulate the interactions using long-wavelength lasers, rather than relying on more traditional techniques that utilize shorter wavelengths.

Enhancing Interactions with Close-Quarter Atoms

For the study, the researchers placed the atoms extremely close to each other—closer than the wavelength of the excitation laser used to trigger these interactions. The closer the atoms are to one another, the more significant their photon-mediated interactions become, which is crucial for quantum entanglement. If the atoms are spaced too far apart, interactions weaken, leading to decoherence, or the loss of quantum information. By having the atoms packed into close proximity, the researchers could ensure that interactions remained strong enough to maintain quantum correlations.

Additionally, Thompson notes that this research is made possible by a special 2.9-micron laser—a laser capable of exciting specific transitions between two excited states in strontium atoms that involve these metastable energy levels. These long-wavelength photons significantly outstrip typical wavelengths used in typical atomic lattice experiments, potentially leading to better-controlled and programmable interactions.

“We plan to build the necessary capabilities in our lab to first excite the atoms in such a way that they can remain in an excited state for extended periods,” Thompson adds. “By utilizing these long-wavelength transitions, we can bring atoms into much closer contact with one another, resulting in more robust interactions.”

The Rise of Spin-Squeezing

A key outcome of the study was the emergence of spin-squeezing in the atomic system. This specific type of entanglement has notable implications for applications in metrology, where systems require extreme sensitivity to external influences. By carefully controlling the polarization and propagation direction of the laser photons exciting the atoms, the researchers were able to study the “spin-wave patterns” of atomic entanglement across the lattice.

“Spin squeezing in our system is a tangible and measurable signature of quantum entanglement. The setup also has possible applications in simulating many-body physics,” Agarwal remarks. By observing this form of entanglement, the team shows the potential for maintaining quantum entanglement without the need for continuous intervention, paving the way for more stable quantum systems.

Simulating Entanglement Across Lattices

Despite the groundbreaking results, the team’s work also presented some challenges, particularly when it came to simulating the complex dynamics of such large systems. Atom-atom interactions involve long-range forces that introduce additional complexity. While simple models of interactions in short-range systems can often be computed accurately, these models fail when applied to long-range interactions, such as the dipole-dipole interactions seen in their study.

Furthermore, these interactions are anisotropic, meaning their strength and nature depend on the relative positioning and orientation of the atoms, adding to the system’s complexity. Simulating these long-range forces with precision remains a significant challenge, requiring better computational tools to track these dynamics at a large scale.

Towards Large-Scale Quantum Systems

While this study offers valuable insights, it is just one step toward achieving the larger goal of creating scalable and stable quantum systems. As the team continues to explore the use of more extensive multilevel systems, such as strontium with as many as 10 internal states, the complexity increases but so does the potential for maintaining quantum entanglement across large numbers of atoms.

In the future, Agarwal and colleagues plan to explore how these interactions can be further enhanced by integrating them into optical cavities or nanophotonic devices, where the interaction between atoms and photons can be manipulated even further. This has the potential to significantly impact quantum information processing, enabling the development of quantum gates, secure quantum communication systems, and more.

Conclusion

The findings presented by Rey and her collaborators represent a milestone in understanding atom-light interactions in complex, multi-level atomic systems. With promising results related to spin-squeezing and quantum entanglement, their research pushes the boundaries of quantum physics while opening the door for new techniques that could one day play a pivotal role in quantum information science. The ongoing challenge of preserving entanglement and controlling atom-light interactions is essential for advancing quantum technologies, bringing us ever closer to fully realizing their practical applications in the near future.

Reference: Sanaa Agarwal et al, Entanglement Generation in Weakly Driven Arrays of Multilevel Atoms via Dipolar Interactions, Physical Review Letters (2024). DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.133.233003. On arXiv: DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2405.16101