For decades, scientists have regarded the Moon as a geologically inert body, long past its active geological phase. The Moon’s surface has been extensively studied to uncover its complex geological and evolutionary history, and early evidence from the lunar maria (dark, flat regions filled with solidified lava) suggested that the Moon underwent significant compression early in its history. This compression was theorized to have resulted in large arching ridges on the Moon’s near side, believed to be the remnants of a period of contraction that occurred billions of years ago. Consequently, researchers assumed that the Moon’s maria had remained dormant ever since—presumably untouched by significant geological activity.

However, recent findings challenge this long-standing view. A groundbreaking study reveals that the Moon may not be as geologically dead as previously thought, suggesting that it might still be undergoing active tectonic processes. The study, led by two scientists from the Smithsonian Institution and a geologist from the University of Maryland (UMD), uncovered surprising evidence that small ridges on the Moon’s far side are much younger than those previously discovered on the near side. These ridges were found to have formed much more recently—within the last 200 million years, a relatively brief period on the Moon’s extensive geological timescale.

This new discovery opens up new possibilities about the Moon’s current geological activity and holds important implications for future lunar exploration.

The Discovery of Younger Ridges on the Far Side

Historically, researchers have believed that the Moon’s tectonic movements occurred primarily two to three billion years ago. Evidence of volcanic activity from this era is evident in the Moon’s lava plains, known as the maria, which provided scientists with insights into the Moon’s distant past. Large, arcing ridges that extend across the Moon’s surface were attributed to contractions that happened during the early days of the Moon’s history as it cooled down.

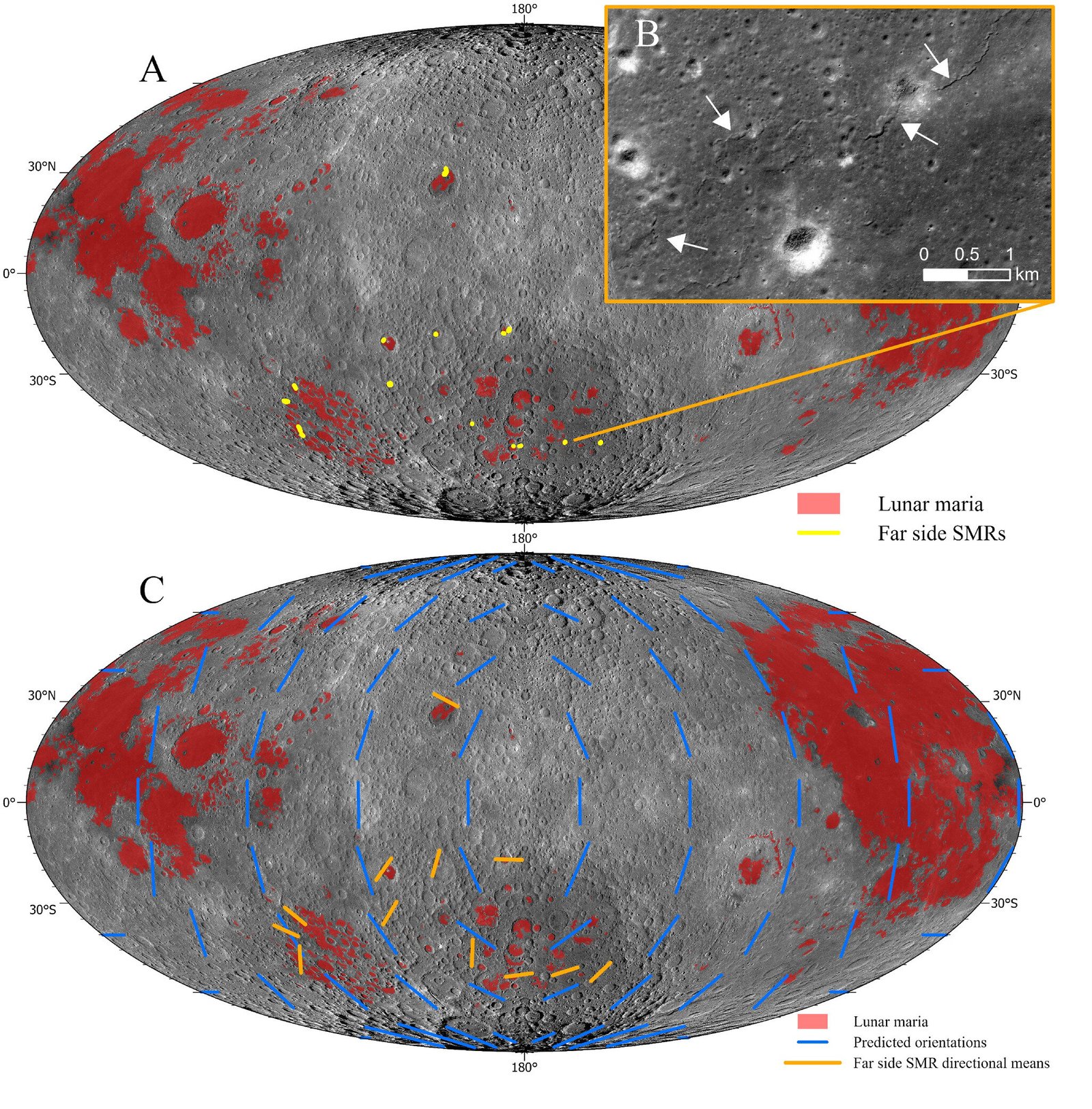

However, the recent study has revealed that these interpretations might have been too simplistic. The team, which included Jaclyn Clark, an assistant research scientist in the Department of Geology at UMD, discovered a cluster of 266 small ridges on the Moon’s far side, none of which had been previously documented. These ridges were primarily found within volcanic regions that are believed to have formed between 3.2 and 3.6 billion years ago, with certain geological areas displaying weaknesses in the lunar surface that could account for the ridges’ formation.

Utilizing advanced mapping and modeling techniques, the researchers estimated the age of these small ridges using crater counting—a method that determines the relative age of surfaces by examining the number of craters that have accumulated over time. Clark explained, “Essentially, the more craters a surface has, the older it is; the surface has had more time to accumulate craters. After counting the craters around these small ridges and seeing that some of the ridges cut through existing impact craters, we believe these landforms were tectonically active in the last 160 million years.”

This groundbreaking finding suggests that the Moon has not been geologically inactive for as long as scientists had once believed, potentially indicating ongoing tectonic processes. This revelation challenges the long-standing assumption that the Moon’s tectonic activity ceased billions of years ago.

Similarities Between the Near and Far Sides

What is especially striking is that the small ridges on the Moon’s far side exhibit structural similarities to those on the near side. Researchers believe both groups of ridges were likely created by the same geological forces, specifically a combination of the Moon’s gradual shrinking and shifts in the lunar orbit. According to the team, these processes may have caused the Moon’s surface to contract over time, leading to the formation of the ridges.

Moreover, the study draws attention to the similarities between the lunar far-side ridges and previously detected seismic activity. In the 1960s and 1970s, the Apollo missions detected small, shallow quakes on the Moon, dubbed “moonquakes.” Many of these quakes were believed to originate deep within the Moon’s crust, suggesting a potentially dynamic interior.

Clark speculates that the formation of these small ridges may be connected to similar seismic activity detected by the Apollo missions. This suggests that seismic forces could still be affecting the Moon’s surface today. Notably, this seismic activity could have a bearing on the lunar surface’s ability to retain small tectonic movements. The ridges may be the surface expressions of deeper processes still occurring within the Moon’s mantle or interior.

Implications for Future Lunar Missions

The newfound evidence of the Moon’s ongoing geological activity holds significant implications for future lunar exploration. As humanity plans to return to the Moon for research and potential colonization, understanding the dynamic nature of its surface becomes critical. Researchers caution that areas that may seem geologically stable could harbor unexpected risks for astronauts and infrastructure.

As Clark noted, “Knowing that the Moon is still geologically dynamic has very real implications for where we’re planning to put our astronauts, equipment, and infrastructure on the Moon.” The study highlights the importance of incorporating advanced tools and technologies for investigating lunar geology, particularly tools capable of probing beneath the lunar surface. For instance, the use of ground-penetrating radar could offer researchers detailed insights into the structures deep within the Moon’s crust and mantle.

This new understanding of the Moon’s geological activity is particularly important because, until now, scientists had largely assumed the lunar surface was stagnant. Knowledge of past or even ongoing seismic activity could drastically change how lunar bases, observatories, and landing sites are chosen in the future.

Conclusion

The Moon, which many have regarded as a silent and geologically dead body, may have been more dynamic in its past—and continues to be so even today. New research reveals that tectonic movements may still be occurring on the Moon, offering valuable insights into the planet’s geological history and its potential for future exploration. The discovery of relatively young ridges on the far side of the Moon challenges decades of assumptions about the Moon’s inactivity and suggests that scientific investigation of this celestial body has much more to uncover.

Understanding that the Moon may still be geologically active is an important consideration for those planning future lunar missions. While the Moon’s surface may appear dormant, tectonic forces could still be at play beneath its crust, affecting exploration efforts and long-term plans for humanity’s return to the lunar surface. In the coming years, future missions, perhaps with advanced ground-penetrating radar, could provide more detailed maps of lunar geology and help scientists unlock more mysteries about Earth’s closest neighbor in space.

Reference: C. A. Nypaver et al, Recent Tectonic Deformation of the Lunar Farside Mare and South Pole–Aitken Basin, The Planetary Science Journal (2025). DOI: 10.3847/PSJ/ad9eaa