Astronomers have discovered an astounding variety of exoplanets—planets orbiting stars outside our solar system—that challenge our understanding of what constitutes a habitable world. From balls of lava with surface temperatures akin to the surface of the Sun to planets potentially raining molten iron, the diversity of these worlds is extraordinary. Some exoplanets even appear to be partially made of diamond. However, not all of these distant worlds are extreme in nature. A significant number of rocky, Earth-sized exoplanets lie in the habitable zones of their stars—regions where conditions might allow for liquid water to exist on the planet’s surface. But can life as we know it survive on these less extreme exoplanets? New research is taking a novel approach to answering that question by considering the importance of a planet’s atmosphere in supporting life.

Traditional Definitions of the Habitable Zone

The traditional definition of a planet’s habitable zone (HZ) is based on the presence of liquid water. The habitable zone refers to the region around a star where the conditions are just right for liquid water to exist on a planet’s surface. In simple terms, if a planet is too close to its star, water would evaporate, and if it is too far, water would freeze. However, this definition is somewhat limited because it does not account for other critical factors that affect habitability, such as the composition and dynamics of a planet’s atmosphere.

For many years, the habitable zone was defined solely by distance—the region where liquid water could potentially exist on the surface of a planet. However, recent research challenges this simplistic view by emphasizing how important a planet’s atmosphere is in determining whether a planet can truly support life.

Rethinking the Habitable Zone: The Role of Atmosphere

In an innovative new study, researchers propose that the atmosphere should be a key factor in defining the habitable zone of a star system. Titled “The Role of Atmospheric Composition in Defining the Habitable Zone Limits and Supporting E. coli Growth,” this study shifts the focus from just the planet’s distance from its star to also consider the potential effects of different atmospheric compositions on habitability.

The research, led by Asena Kuzucan, a post-doctoral researcher in the Department of Astronomy at the University of Geneva, is based on the idea that the atmosphere of an exoplanet plays a crucial role in supporting or hindering life. The study used laboratory experiments to simulate different atmospheric conditions and see if microbial life—specifically, E. coli bacteria—could survive under these conditions. The goal was to assess how a planet’s atmospheric composition could influence its potential to support life, even in the outer regions of the habitable zone where water may be in a frozen state.

Testing the Idea with Microbial Life

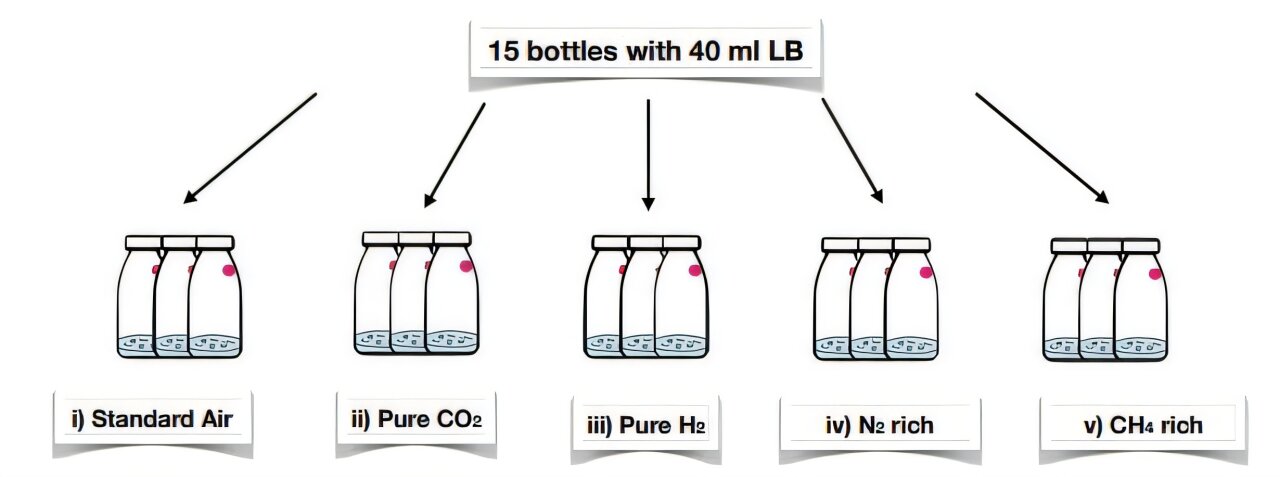

The research team explored a variety of atmospheric compositions, including Earth’s standard air, pure CO2, methane (CH4)-rich atmospheres, nitrogen (N2)-rich atmospheres, and even pure hydrogen (H2). These atmospheric conditions were tested to simulate planets orbiting stars with different temperatures and distances from their stars, particularly at the inner edge of the habitable zone, where the conditions would be extreme for Earth-like life.

In the laboratory, E. coli K-12—a well-studied laboratory strain—was inoculated into 15 separate bottles, each with a different atmospheric composition. The researchers then observed how the bacteria grew and adapted to the different environments. The bacteria were observed for changes in cell density and growth patterns. The findings were enlightening, showing that even in atmospheres that are very different from Earth’s, E. coli could survive and grow under certain conditions.

Atmospheric Composition and Microbial Survival

The study found that some of the most surprising results came from testing pure hydrogen (H2) atmospheres. Though hydrogen-rich atmospheres are typically considered inhospitable for Earth life, the E. coli bacteria showed remarkable resilience in this environment. Even though there was an initial lag in growth as the bacteria adapted to the new environment, the cell density increased significantly after adaptation.

The researchers noted that hydrogen-rich atmospheres supported anaerobic microbial life—microorganisms that do not require oxygen. The ability of E. coli to thrive in an atmosphere dominated by hydrogen suggests that exoplanets with H2-dominated atmospheres could indeed support microbial life, once the organisms have time to acclimatize.

Interestingly, methane (CH4)-rich and nitrogen (N2)-rich atmospheres also supported microbial growth, although the cell density increase was not as dramatic as in the hydrogen-rich environments. This indicates that planets with atmospheres rich in methane or nitrogen could still offer viable conditions for microbial life, provided they are capable of adaptation over time.

Conversely, the results for a CO2-rich atmosphere were less favorable. The growth of E. coli in a pure CO2 atmosphere was much slower than in the other atmospheric scenarios. This suggests that high levels of carbon dioxide may be detrimental to the survival of Earth-like organisms, at least in terms of promoting growth. However, the authors point out that some life forms, particularly chemotrophs or extremophiles, may be adapted to thrive in CO2-heavy environments.

Implications for Habitability and Exoplanet Research

The study’s results have significant implications for how scientists assess the habitability of exoplanets. The researchers concluded that the composition of a planet’s atmosphere is critical for determining whether it can support life. Even planets located near the inner edge of the traditional habitable zone may still harbor life if they possess an atmosphere that allows for the existence of liquid water or other crucial conditions.

The authors also point out that while their findings are based on Earth-centric ideas of life, they could have broader implications. If E. coli can adapt to survive in these extreme atmospheric conditions, it suggests that life forms elsewhere in the universe could be more resilient and adaptable than we currently imagine. Planets with atmospheres dominated by methane, nitrogen, or even hydrogen could still host life forms that are vastly different from Earth-based organisms.

Additionally, the research highlights the complexity of planetary atmospheres and how they interact with various planetary factors such as orbital distance, planetary pressure, and temperature. The team used General Circulation Model (GCM) simulations to study how different atmospheric compositions influence the inner edge of the habitable zone, and their results suggest that planets with H2-dominated atmospheres could extend the habitable zone of their star out to 1.4 AU (astronomical units), a distance farther than CO2-rich atmospheres, which are limited to 1.2 AU.

The Broader Implications

This study represents a step forward in understanding the limits of habitability for exoplanets. By combining atmospheric simulations with biological experiments, the research team has provided insights into how different gases in a planet’s atmosphere can influence its ability to support life. These findings are significant because they highlight how atmospheric conditions—and not just distance from a star—should be considered when searching for habitable exoplanets.

Although some of the atmospheric scenarios tested in the study, such as 1-bar hydrogen or CO2, may not realistically persist over long geological timescales, they still provide valuable insights into the radiative effects of these gases on a planet’s climate and habitability. Furthermore, the study emphasizes the resilience of life forms like E. coli and the potential for microbial life to adapt to a variety of extreme conditions, further expanding our understanding of where life could exist beyond Earth.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the research conducted by Asena Kuzucan and her team underscores the importance of considering atmospheric composition when assessing the habitability of exoplanets. The ability of microbes like E. coli to survive and adapt to atmospheres rich in hydrogen, methane, or nitrogen suggests that life could thrive in a wider range of environments than previously thought. This opens up new possibilities for the search for life beyond Earth and challenges our Earth-centric view of habitability. As astronomers continue to search for exoplanets, this research helps refine the parameters we use to identify potentially habitable worlds—worlds where life may exist in ways we have yet to fully understand.

Reference: Asena Kuzucan et al, The Role of Atmospheric Composition in Defining the Habitable Zone Limits and Supporting E. coli Growth, arXiv (2025). DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2501.05297