Dr. Nobuyuki Kawai, a researcher from Nagoya University in Japan, has uncovered significant findings that shed light on how monkeys detect snakes rapidly and specifically respond to them. His research, published in Scientific Reports, reveals that monkeys’ quick identification of snakes is driven by the presence of snake scales, a distinctive visual cue that serves as an evolutionary adaptation. This discovery contributes to our understanding of how primates have evolved specialized visual processing mechanisms to detect threats in their environment.

The rapid detection of potential dangers plays a crucial role in the survival of many species, including primates. Throughout evolutionary history, snakes have posed a major threat to primates, including humans, with their venomous bites and ability to strike quickly. This threat has likely led to the development of heightened awareness and specialized responses to snakes. Remarkably, the ability to recognize and react to snakes seems to be innate, as even human infants and monkeys that have never encountered a snake exhibit a strong response to images of them. This suggests that our fear of snakes may be deeply ingrained, rather than learned from experience.

Kawai’s research provides further evidence of this innate response and uncovers the specific visual features that trigger it. His experiments focused on understanding why monkeys are able to identify snakes so quickly. In his first experiment, Kawai observed that monkeys displayed a quick reaction to images of snakes, but not to salamanders. This was a significant finding because both snakes and salamanders share similar body shapes—elongated bodies and tails—which would lead to the assumption that monkeys might respond to them in a similar manner. However, the fact that monkeys showed a stronger response to snakes suggests a specific and evolved fear of these reptiles.

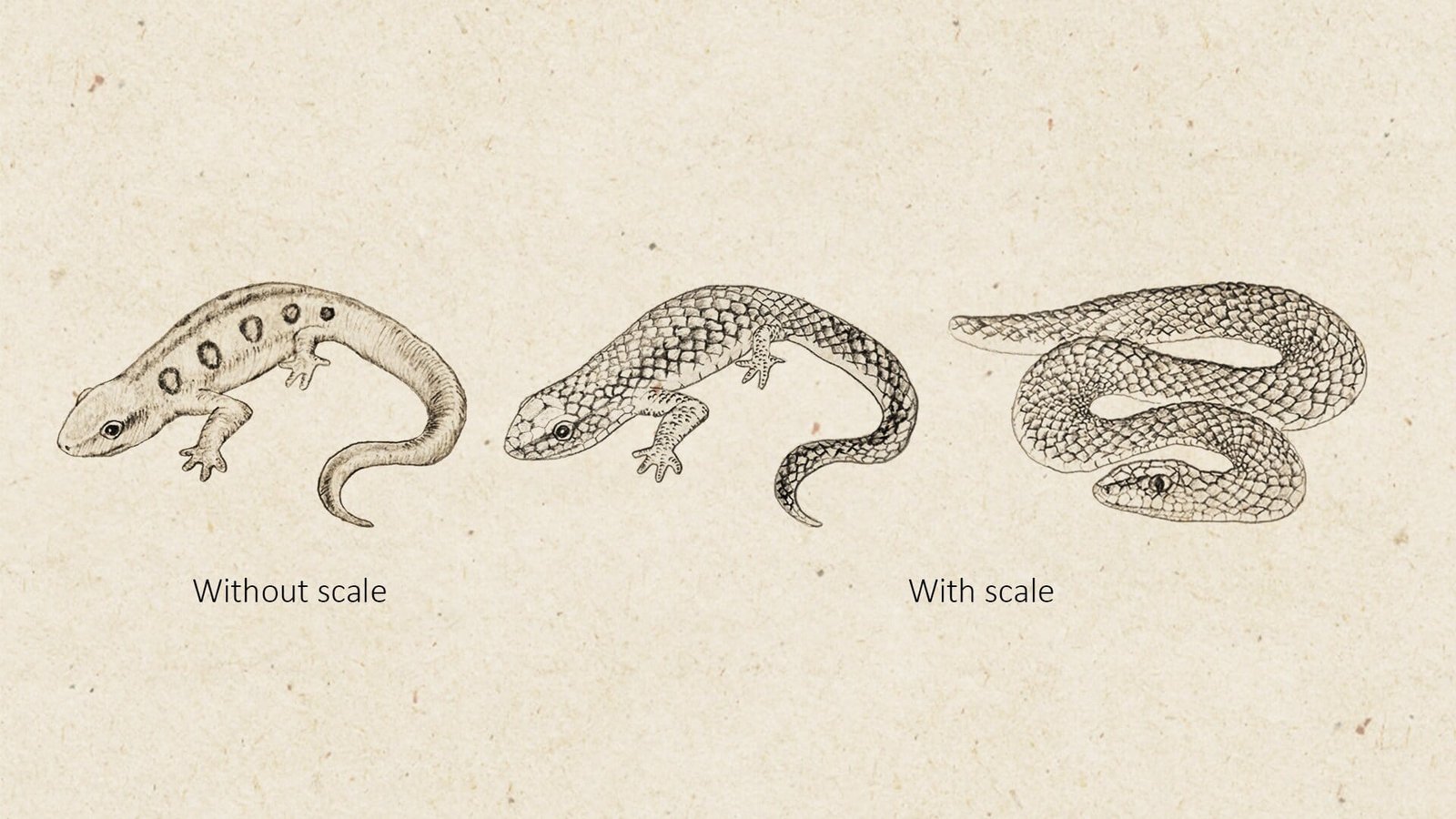

Following this initial experiment, Kawai hypothesized that there might be a particular visual cue that monkeys use to distinguish snakes from other similar-looking animals. Specifically, he wondered whether the presence of snake scales might be the key factor. To test this hypothesis, Kawai conducted an experiment in which he manipulated images of salamanders, covering them with snakeskin patterns without altering the rest of the creature’s features. He wanted to see if monkeys would respond more strongly to salamanders with snake-like scales, even though the animals were harmless.

The results were striking. Monkeys that had never encountered a real snake responded more rapidly to images of salamanders that were edited to look like snakes, showing a faster reaction time to these altered images than to the original snakes. This suggested that the monkeys were specifically reacting to the scales, rather than the overall body shape of the animal. Interestingly, the monkeys did not show a faster response when a salamander was presented alongside a group of snakes, indicating that it wasn’t just the elongated body shape that triggered their response, but the presence of snake scales.

This experiment led Kawai to the conclusion that scales themselves are a critical visual cue that monkeys use to identify snakes. The evolutionary significance of this finding lies in the fact that primates, including humans, have developed a visual system that can recognize the presence of scales, a feature unique to snakes among many animals. This ability would have been incredibly useful for early primates in avoiding dangerous encounters with venomous snakes, thus enhancing their chances of survival. The recognition of snake scales, therefore, likely provided a significant evolutionary advantage, allowing primates to react quickly to potential threats.

Kawai’s work builds on previous research that demonstrated the ability of both humans and primates to recognize snakes rapidly, but his findings go further in identifying the specific visual feature that triggers this response. According to Kawai, “The monkeys did not react faster to salamanders, a species that shares a similar elongated body and tail with snakes, until the images were changed to cover them with snakeskin.” This indicates that the presence of scales plays a central role in triggering a fear response in primates.

Furthermore, Kawai’s study suggests that the evolution of visual processing systems in primates, including humans, has been shaped by the need to detect and respond to threats like snakes. The ability to recognize snake scales likely developed over time as part of an adaptive strategy for avoiding danger. This visual cue, coupled with an innate fear of snakes, would have helped early primates avoid the dangers posed by these reptiles, ensuring their survival and facilitating their evolutionary success.

These findings not only deepen our understanding of the evolution of visual processing in primates, but they also offer insights into broader questions about brain evolution and threat detection mechanisms in animals. By studying how monkeys and other animals perceive and respond to threats, researchers can gain a better understanding of how our own brains process visual information and make quick decisions based on it. The ability to identify and react to potential dangers is a critical aspect of survival, and Kawai’s research highlights how this skill has evolved in primates, including humans.

Kawai’s study also emphasizes the importance of studying the visual systems of animals to better understand their behavior and evolutionary history. The fact that monkeys react so strongly to snake scales, even without prior exposure to snakes, suggests that there are deeply ingrained mechanisms in the brain that are hardwired to recognize certain patterns associated with danger. This has implications for the study of innate behaviors and how animals process sensory information in ways that enhance their survival.

Reference: Nobuyuki Kawai, Japanese monkeys rapidly noticed snake-scale cladded salamanders, similar to detecting snakes, Scientific Reports (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41598-024-78595-w

Think this is important? Spread the knowledge! Share now.