A groundbreaking study by a large and diverse team of researchers at the Chinese Academy of Sciences has provided new evidence that the Moon had a weak magnetic field about 2 billion years ago. The study, published in Science Advances, used rock samples collected by China’s Chang’e-5 mission to analyze the history of the Moon’s magnetic field. The Moon’s magnetic field has long been a topic of scientific interest, as it is believed to have existed in some form during the early stages of the Moon’s history but has since disappeared.

Benjamin Weiss, a scientist from MIT, also contributed to the Science Advances issue with a Focus piece providing background information on previous research and context for this new discovery. Weiss’s article explores the history of lunar magnetism and the relevance of this new evidence in furthering our understanding of the Moon’s geological past.

The Chang’e-5 mission, which landed on the Moon in December 2020, successfully returned a significant cargo of 1,731 grams of lunar rock and soil samples. These samples were studied by various research teams, and the new study represents the latest findings from the analysis of some of these lunar materials. The research team’s objective was to gain insights into the early history of the Moon and its magnetic field, particularly to understand whether the Moon’s internal processes were capable of generating a magnetosphere or dynamo.

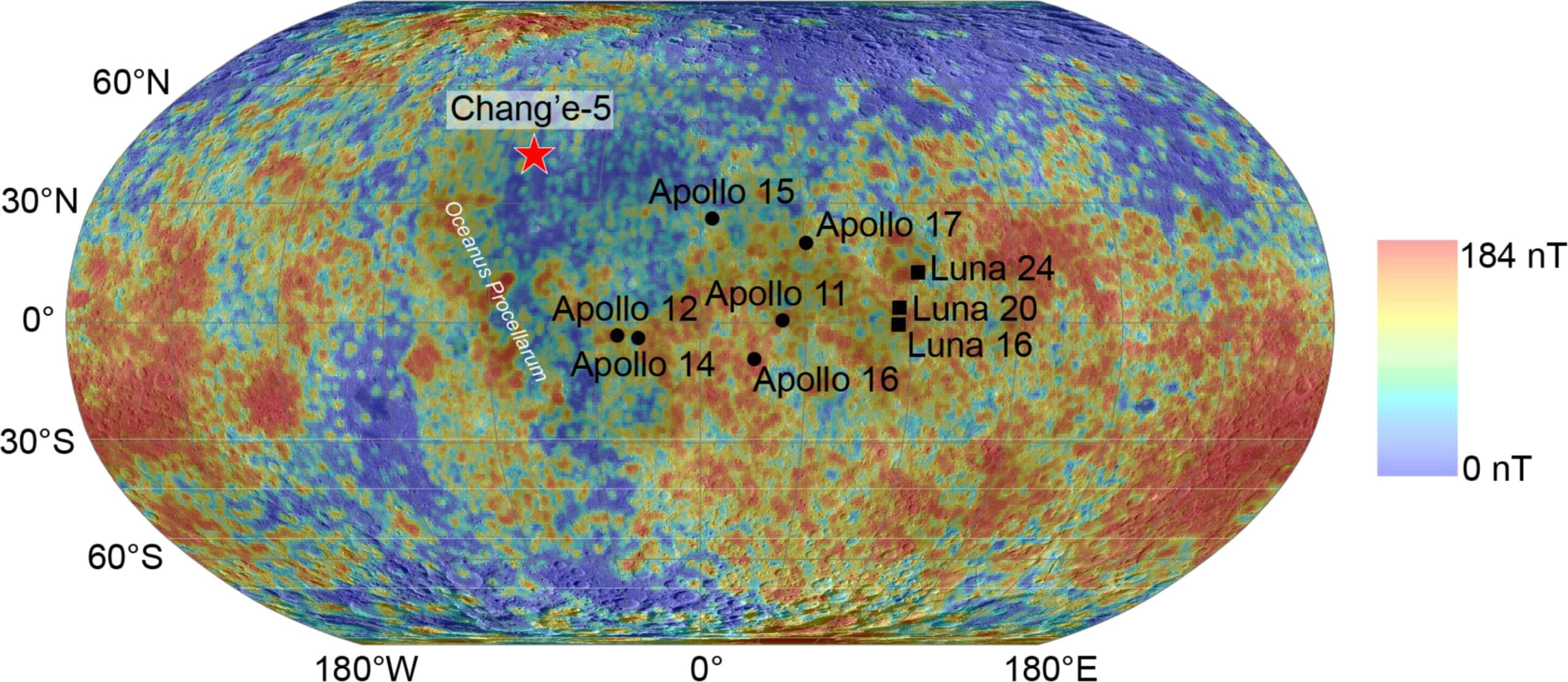

Currently, the Moon does not possess a global magnetic field. However, scientists have long believed that the Moon once did, powered by thermomechanical convection deep within its interior. This process is believed to have generated a dynamo effect, the same fundamental process that drives Earth’s magnetic field. Previous studies of lunar rocks returned by the Apollo astronauts and the Soviet Union’s Luna missions indicated that a weak magnetic field existed on the Moon roughly 4 billion years ago. This magnetic field, although much weaker than Earth’s (about 1/20th the strength), indicated that the Moon once had molten fluids beneath its surface.

The team’s recent study of lunar rock samples gathered by Chang’e-5—mostly basaltic rock—has led to the conclusion that the Moon’s magnetic field persisted much longer than previous research suggested. By analyzing these samples, the team estimated that the Moon’s magnetic field was active around 2 billion years ago and had a strength ranging between 2,000 and 4,000 nanoteslas. This is a significant development as it suggests that the dynamo that produced the magnetic field was operational far longer than the prevailing models had proposed.

The findings have major implications for our understanding of the Moon’s geological and thermal history. Until this new research, it was widely believed that the Moon had cooled enough by about 3 billion years ago that any molten material, particularly in its interior, would have solidified, ending its magnetic dynamo. The new evidence implies that the Moon continued to host a molten interior for a much longer period than scientists had previously thought, perhaps as late as 2 billion years ago. This is a crucial piece of the puzzle in understanding the Moon’s evolutionary history, as it challenges previous models of lunar cooling and interior solidification.

Moreover, this study suggests that the Moon may have experienced significant volcanism much later in its history than scientists previously assumed. Volcanic activity typically occurs when the Moon’s interior is still hot enough to maintain molten rock, and the presence of a magnetic field provides a new piece of evidence supporting this hypothesis. The discovery of late-stage volcanism implies that the Moon’s geological activity lasted longer than earlier research has indicated, challenging older views that the Moon became geologically inactive much earlier.

Another exciting implication of the study is related to the Moon’s potential role in the preservation of water. As the researchers point out, a weak magnetic field would have acted as a shield to protect water from the solar wind. The solar wind, a stream of charged particles emitted by the Sun, has the potential to strip away the atmosphere and surface elements of celestial bodies, converting water into other materials. If the Moon had a magnetic field at this time, it could have prevented such interactions, shielding any frozen water at the poles and possibly maintaining small reserves of water in the Moon’s permanently shadowed regions.

This evidence also fuels speculation about the history of water on the Moon. For many years, scientists have hypothesized that the Moon might have been able to support water in some form—either as frozen ice in shadowed craters at the poles or in trace amounts within the lunar regolith. The presence of a magnetic field over an extended period could have preserved water on the surface and in the subsurface for a more extended period, potentially providing the conditions necessary for more complex geological and atmospheric interactions.

As scientists continue to analyze the lunar samples from Chang’e-5, we are gaining a more detailed picture of the Moon’s dynamic history, one that was far more geologically active and capable of sustaining molten material and potential water far longer than we once imagined. These findings represent a crucial advancement in our understanding of the Moon and contribute to a larger understanding of the potential for life-supporting conditions on other planetary bodies, especially in the context of the ongoing exploration of the Moon, Mars, and other distant worlds.

The Moon’s magnetic history and its geological evolution are critical to interpreting the planet’s role in the solar system’s early development. By building on discoveries like this, researchers are providing insights not only into the history of our closest celestial neighbor but also into the broader processes that shaped the Moon, the Earth, and other planetary bodies in our solar system.

Ultimately, the continued research and the collaborative efforts of international teams represent an exciting chapter in lunar science. With future missions aimed at returning humans to the Moon and establishing a sustainable presence there, the ongoing study of the Moon’s geological past will help shape future exploration efforts and our understanding of what makes planetary bodies habitable, or at least capable of hosting essential elements like water.

References: Shuhui Cai et al, Persistent but weak magnetic field at the Moon’s midstage revealed by Chang’e-5 basalt, Science Advances (2025). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adp3333

Benjamin P. Weiss, The Moon goddess’s magnetic midlife, Science Advances (2025). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adu7441

Think this is important? Spread the knowledge! Share now.