The “forever chemicals,” a term used to describe persistent chemicals that do not degrade easily in the environment, have been a growing concern for environmental and public health experts. New research from a multi-university study has raised alarming concerns regarding the ubiquity and persistence of these chemicals in wastewater. The study reveals that not only are “forever chemicals” more prevalent than previously thought, but their primary composition consists of pharmaceuticals that have received minimal attention from the scientific community and regulatory agencies.

Published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the research indicates that approximately 75% of the organic fluorine found in wastewater entering treatment plants comes from common prescription drugs. Even more concerning is that these pharmaceuticals, along with other fluorinated chemicals, make up about 62% of the organic fluorine in treated water that is released into the environment. This new finding challenges the assumption that the most widely known “forever chemicals” are the main contaminants in our water supplies, pointing instead to an extensive, largely unregulated group of fluorinated pharmaceuticals that could be affecting millions of Americans.

The impact of these chemicals on public health has been unclear. These substances are particularly concerning because they are designed to remain biologically active at very low doses. This means that even minimal exposure to these compounds could pose a risk, especially when people are consistently exposed through drinking water.

The study, led by Bridger J. Ruyle, an incoming assistant professor at NYU Tandon School of Engineering, emphasizes the alarming gap in knowledge about these chemicals. “We’ve been focused on a small subset of these chemicals, but that’s just the tip of the iceberg,” Ruyle stated. “What we’ve found in our research shows that current wastewater treatment methods are not doing nearly enough to remove these compounds from the environment.”

In fact, even advanced wastewater treatment technologies remove less than 25% of these chemicals before they are discharged into rivers and streams. That means a large proportion of the chemicals remain in the effluent that is released into our environment and may ultimately enter the water supply. Six “forever chemicals” recently regulated by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in drinking water make up only about 8% of the organic fluorine found in wastewater effluent. The rest of the organic fluorine consists primarily of fluorinated pharmaceuticals that have largely escaped regulation, leaving a gaping hole in public health protections against these chemicals.

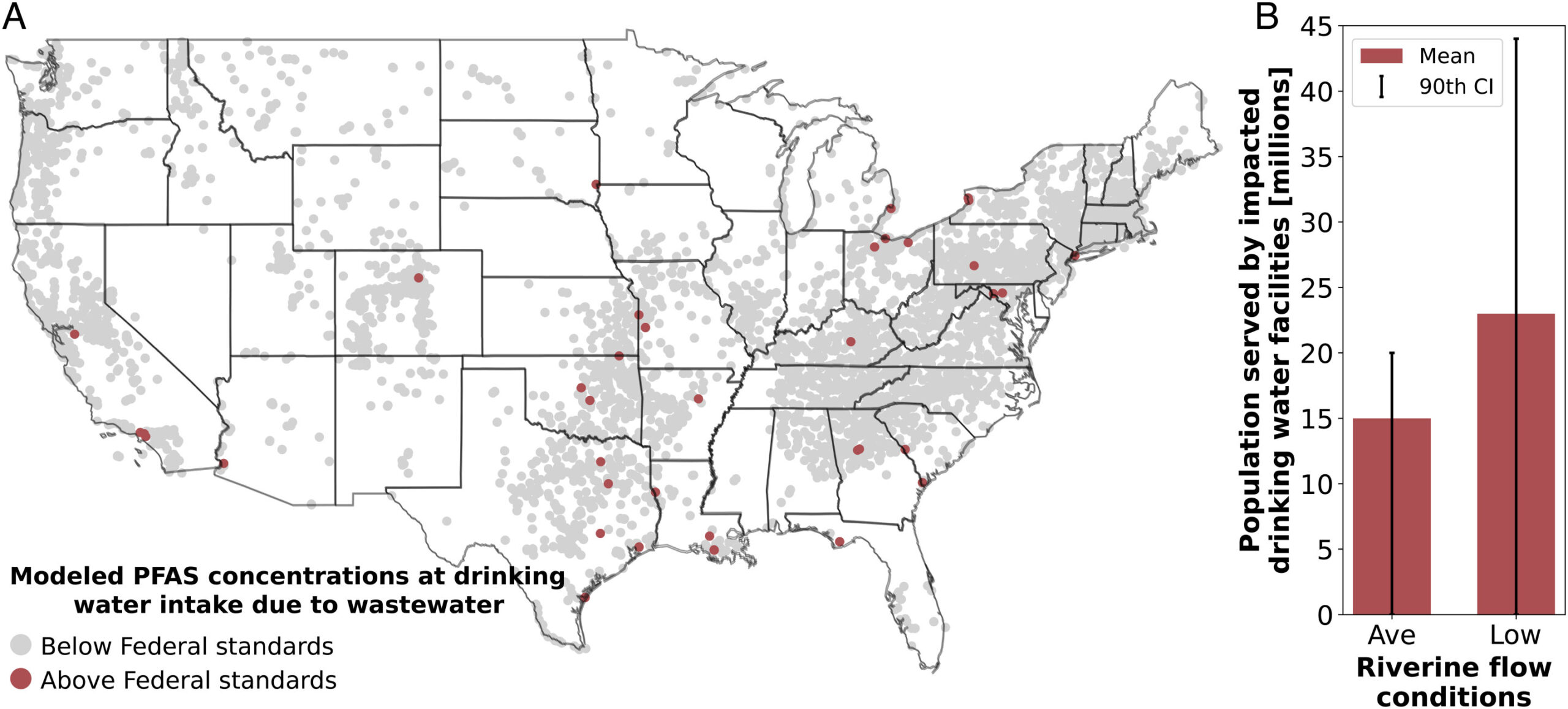

Using a national model of how wastewater travels through U.S. waterways, the researchers also estimated that around 15 million Americans are drinking water that contains levels of these unregulated compounds above the regulatory limits under normal river conditions. This number could rise even higher—up to 23 million—during drought conditions when water is more concentrated and less diluted.

The study’s findings were based on data from eight large wastewater treatment facilities in metropolitan areas, serving roughly 70% of the U.S. population. This means that the study’s implications extend nationwide. “The breadth of these findings highlights the potential scale of the issue and its relevance to communities all over the country,” Ruyle said.

Fluorine is widely used in pharmaceuticals for its effectiveness in making drugs persist longer in the body. While this attribute helps improve the performance of drugs, it also means that these drugs—when they enter the wastewater system—do not easily degrade or break down. Instead, they persist in the environment, accumulating in water supplies and, in some cases, reaching harmful concentrations. This persistence could present serious long-term risks to human and ecosystem health, especially given the limited regulatory frameworks currently in place.

The troubling findings point to a major problem with current regulatory approaches to managing “forever chemicals.” Many regulations are focused on individual chemicals, but the reality is that there is a much broader mixture of fluorinated compounds in our wastewater, a large portion of which currently receives little scrutiny or regulation. “We’re focusing on a small fraction of chemicals in wastewater when the reality is that we need to address a far more complex mixture of harmful compounds,” Ruyle explained. This broad mix could be having far more significant effects than previously understood, and the oversight framework is insufficient for ensuring water safety in the long term.

One key factor contributing to this problem is water scarcity, especially during drought conditions. When water is scarce, municipalities often turn to wastewater reuse, using treated wastewater as a source for drinking water. In such cases, there is even less dilution of the chemicals that remain in the wastewater before it is processed and delivered to residents. As regions increasingly adopt water conservation measures or rely on reused wastewater, the concentration of chemicals in the drinking water supply may rise, exacerbating the risk to public health.

The study underscores the urgency of addressing ongoing sources of these chemicals and reevaluating our approach to regulating them. Researchers call for a more comprehensive strategy that focuses not only on individual chemicals but on the full scope of fluorinated pharmaceuticals and related compounds that may pose risks to human health and the environment. Ruyle and his team advocate for a deeper examination of the effects of prolonged exposure to these chemicals through drinking water, which has not received sufficient scientific attention up until now.

This research is timely, as fluorine is found in approximately 20% of all pharmaceuticals today. While the chemical’s effectiveness at enhancing drug stability in the body is valuable, its persistence in the environment is detrimental. The current focus on specific, well-known contaminants, such as per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), which have recently drawn the attention of the EPA, might not be enough. While PFAS are often highlighted as the primary “forever chemicals,” the vast array of fluorinated compounds in wastewater has been largely ignored.

The findings of this study were presented by Ruyle to New York State lawmakers in a testimony in November 2024, highlighting the risk that “forever chemicals” passing through water treatment plants may pose. These findings further substantiate the concerns raised in his testimony, offering scientific evidence of the persistence and widespread nature of these compounds in the nation’s water systems. The results advocate for urgent action to strengthen the regulation and remediation of these chemicals.

In light of the study’s findings, researchers stress the importance of action at the national level. While local and state governments may respond to issues of water contamination, federal regulatory agencies and public health authorities must take a more proactive role in ensuring that water safety standards address the broader range of contaminants, particularly fluorinated pharmaceuticals.

“Current regulatory practices are not equipped to handle this mix of chemicals,” said Ruyle. “We need a new framework for evaluating and mitigating risks to public health.” It’s clear from the research that merely regulating a select few contaminants will not suffice to protect public health. The full scope of this problem requires a national, holistic approach that takes the complexity of wastewater contamination into account.

This study shines a much-needed light on a rapidly growing issue and highlights the gap in our understanding of the long-term effects of widespread exposure to unregulated fluorinated chemicals. Going forward, the challenge will be to ensure that both the scientific community and regulatory agencies take swift and comprehensive action to limit exposure and safeguard public health in the face of these persistent pollutants.

Reference: Bridger J. Ruyle et al, High organofluorine concentrations in municipal wastewater affect downstream drinking water supplies for millions of Americans, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2025). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2417156122

Think this is important? Spread the knowledge! Share now.