In an unprecedented new study, researchers have uncovered how neurotransmitters in the human brain are released during the processing of emotional content in language. This groundbreaking research, led by an international team headed by Virginia Tech scientists, offers novel insights into how the brain interprets and responds to the emotional significance of words, deepening our understanding of the connection between language and human emotions.

The study, spearheaded by computational neuroscientist Read Montague, a professor at the Fralin Biomedical Research Institute at VTC and director of its Center for Human Neuroscience Research, represents the first of its kind to investigate how neurotransmitters, such as dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine, influence the processing of emotionally charged language. These neurotransmitters have long been associated with regulating mood, reward, and emotional responses, but this research sheds new light on their role in language interpretation—a distinctly human cognitive function that links emotions and communication in a unique way.

The findings, which are scheduled for publication in the Jan. 28 issue of Cell Reports, bridge the gap between biology and symbolism. They link the neural processes that evolved in various species to respond to environmental stimuli with the complexities of human communication, which includes interpreting the emotional weight of words. Montague, co-corresponding and co-senior author of the study, explained that neurotransmitters like dopamine and serotonin have traditionally been understood as signaling agents related to the positive or negative value of experiences. However, this research suggests that these chemicals are not merely tied to general emotional experiences but are also released when processing the emotional meaning embedded within language itself.

“Our research shows that neurotransmitters are released in specific areas of the brain when we process the emotional content of words,” Montague explained. “This indicates that the brain systems that evolved to help us respond to good or bad things in our environment might also be involved in processing words, which, like environmental stimuli, are integral to our survival.”

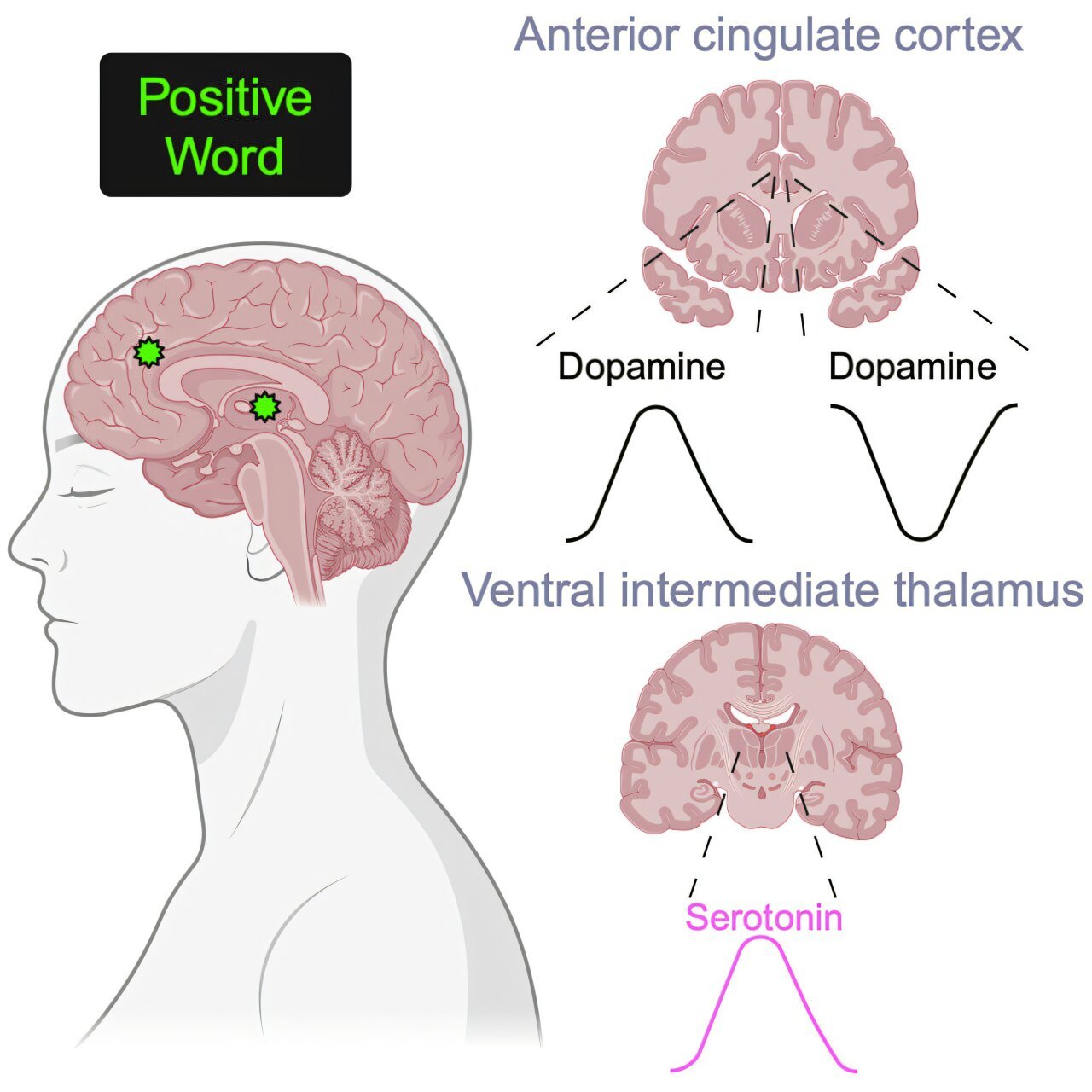

The study represents a pioneering effort to simultaneously measure the release of dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine in human brains while examining how individuals interpret emotionally charged language. By utilizing sophisticated tools to monitor neurotransmitter activity, the researchers were able to track the dynamics of these chemicals during word processing. The results revealed that emotionally significant words—whether positive, negative, or neutral—modulated neurotransmitter release in distinct ways across different brain regions and hemispheres. Importantly, this process was far more intricate than the simplistic model of one chemical correlating to a specific emotion. Instead, the researchers found that multiple neurotransmitter systems are involved in processing the emotional content of language, and each system fluctuates differently depending on the emotional tone of the words and the specific area of the brain being activated.

To measure neurotransmitter activity, the research team conducted experiments on patients undergoing deep brain stimulation surgery for the treatment of essential tremor or for the surgical implantation of electrodes to monitor seizures in epilepsy patients. These procedures targeted different brain regions, namely the thalamus and the anterior cingulate cortex, which allowed the researchers to assess neurotransmitter release in response to emotional words while simultaneously studying brain regions typically associated with emotional and linguistic processing. Using carbon fiber electrodes in the thalamus and platinum-iridium electrodes in the anterior cingulate cortex, the researchers displayed emotionally charged words on a screen while measuring the dynamic release of neurotransmitters.

The results were eye-opening, particularly in the case of the thalamus. This brain region, which had not previously been linked to emotional or linguistic processing, showed distinct changes in neurotransmitter levels when patients were exposed to emotional words. This discovery suggests that even brain areas not typically associated with processing emotions or language may still play a role in interpreting the emotional significance of words. The thalamus, for example, is primarily involved in relaying sensory information and coordinating movement, but the findings imply that it may also provide valuable input to higher cognitive systems when emotional content is involved, guiding behavioral responses to emotionally charged words.

William “Matt” Howe, an assistant professor at the School of Neuroscience at Virginia Tech and a co-author of the study, remarked that the results were surprising. “The thalamus has long been considered a relay station for sensory information, but we saw neurotransmitter changes in response to emotional words,” he said. “This suggests that even brain regions responsible for functions like movement could benefit from access to emotionally significant information, which could help guide behavior in response to emotional stimuli.”

The findings were not limited to human studies. The researchers also conducted experiments in rodent models to validate their results. Using a technique called optogenetics, which enables researchers to control genetically modified cells using light, the team was able to study specific neurons and neural circuits involved in emotional processing. The confirmation of these findings in rodents adds weight to the broader implications of the research, reinforcing the idea that neurotransmitter systems play an important role in interpreting emotional content, not just in humans, but across species.

Alec Hartle, a doctoral student at the Virginia Tech School of Neuroscience and a co-first author of the study, emphasized the significance of the rodent experiments. “By using optogenetics to control neural activity in animals, we were able to replicate and confirm the neurotransmitter patterns we observed in the human brain,” Hartle explained. “This cross-species validation supports the idea that neurotransmitters like dopamine and serotonin are integral to systems involved in decision-making, which includes processing emotional language.”

The research expands on a previous study by Montague’s team, published in Nature Human Behavior, which explored how dopamine and serotonin influence social behavior. While the earlier study focused on the role of neurotransmitters in decision-making, this new research delves into a uniquely human aspect of cognition: the emotional content of language. Unlike animals, humans can attach complex emotional and social meaning to words, which adds a layer of nuance to our communication. The study posits that the neurotransmitter systems responsible for regulating survival-related behavior also play a key role in interpreting language, a function essential for social interaction, decision-making, and overall human well-being.

Seth Batten, the first author of the study and a senior research associate in Montague’s lab, highlighted the novelty of the findings. “Previous research on neurotransmission focused on decision-making, but this study is about understanding something distinctly human: how we process the emotional content of words,” he explained. “Our research suggests that the brain’s reward and emotional systems, which evolved to help us respond to critical environmental stimuli, are also essential for understanding language in a way that shapes our behavior, choices, and interactions.”

While the study is still in its early stages, its significance lies in the foundational insights it provides into the intersection of language, emotion, and brain chemistry. The findings open up several new avenues for future research, particularly in understanding how these neurochemical processes may influence behavior, decision-making, and mental health. For instance, the study’s results may offer new ways to approach disorders related to language processing, such as aphasia or dyslexia, as well as emotional disorders like depression and anxiety, which are often characterized by disruptions in neurotransmitter function.

The words used in the study were drawn from the Affective Norms for English Words (ANEW) database, a comprehensive resource that rates words based on their emotional valence—whether they are perceived as positive, negative, or neutral. This provided a robust framework for examining how words with different emotional weight influence neurotransmitter release in the brain.

Ultimately, this research marks a pivotal step in bridging the gap between the biological processes of the brain and the symbolic, emotional content of language. It not only deepens our understanding of how humans interpret and respond to language but also offers a glimpse into the neurobiological underpinnings of human emotion and decision-making. As future studies build on these findings, we may come to understand more fully how neurotransmitter systems shape our cognitive and emotional lives, ultimately influencing the way we communicate, connect, and make decisions in a complex, emotionally charged world.

Reference: Seth R. Batten et al, Emotional words evoke region- and valence-specific patterns of concurrent neuromodulator release in human thalamus and cortex, Cell Reports (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.celrep.2024.115162