Archaeologists Dr. Jess Thompson and her team have uncovered fascinating insights into Neolithic burial practices in southern Italy, shedding light on how ancient communities maintained connections with their ancestors. The research, recently published in the European Journal of Archaeology, centers on findings from Masseria Candelaro, an ancient village in Puglia. These discoveries provide an in-depth look into the significance of human skulls and their possible use in ancestor veneration rituals, offering a glimpse into the complex spiritual beliefs of Neolithic people.

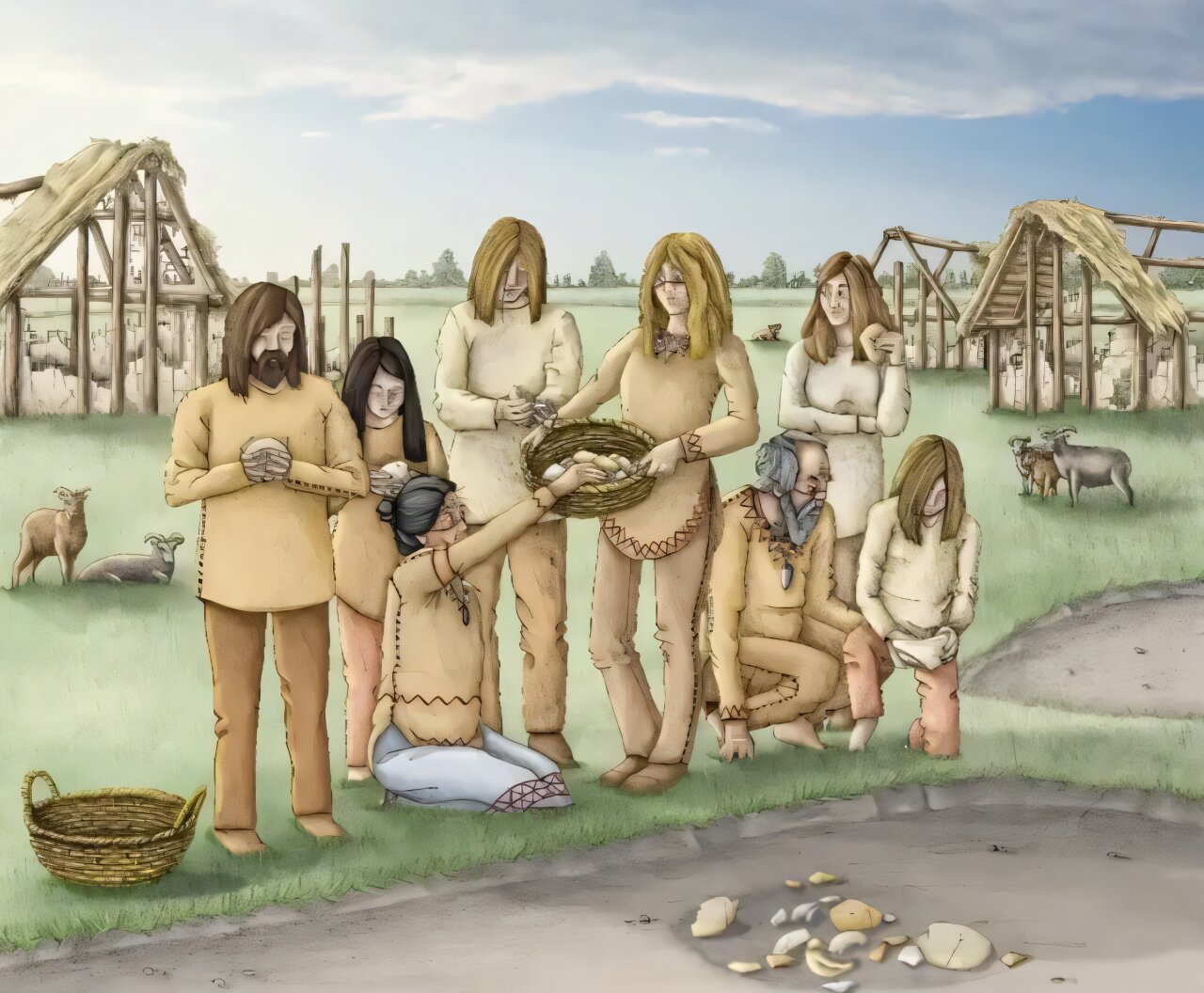

The Neolithic period in southern Italy, spanning from roughly 6000 to 3800 BCE, was characterized by diverse funerary practices. These practices included primary and secondary burials, defleshing, and disarticulation of skeletal remains. Among these, the treatment of skulls and bones stood out as spiritually significant. Evidence suggests that these communities attributed special ritual importance to the head, often treating it in ways that symbolized reverence and continuity with their ancestors.

Masseria Candelaro has been the site of archaeological exploration for decades. Between 1985 and 1993, archaeologists Selene Cassano and Alessandra Manfredini led excavations that primarily focused on settlement remains. During their work, they uncovered human remains and burials scattered across various site features, such as disused pits, silos, external ditches, and abandoned domestic spaces. Among these findings, a particularly intriguing discovery was made in “Structure Q,” a feature containing what is now termed the “cranial cache.”

This cranial cache consisted of disarticulated skulls belonging to at least 15 individuals, with a possible total of up to 53. Researchers employed skull morphology and tooth wear analysis to identify the characteristics of these individuals. Their findings revealed that at least five were male, six were likely male, and the remaining skulls could not be definitively identified by sex. Notably, the cache contained no children, with the youngest individual estimated to be between 12 and 18 years old, while the oldest exceeded 45 years of age.

Signs of repeated handling and wear on the skulls suggested they had been preserved and manipulated post-mortem. This wear included dry breakage, a phenomenon that only occurs long after death. Such evidence raised questions about the purpose of this unusual collection of human remains. Researchers developed two primary hypotheses regarding the deposition and repeated use of these skulls: they could have been war trophies or part of ancestor veneration rituals.

The first hypothesis, that the skulls were trophies of war, seemed unlikely. Typically, war trophies show evidence of perimortem trauma, such as fractures or damage sustained during violent encounters. However, the skulls in the cache showed no such signs of violence. Moreover, there was no evidence of cannibalism or decorative enhancements such as ornamentation or overmodeling, which are often associated with trophy skulls. Strontium isotope analysis further supported this conclusion by revealing that the skulls belonged to local individuals, making it improbable that they were acquired through conflict with external groups.

The second hypothesis, that the skulls were used in ancestor veneration rituals, aligned more closely with the evidence. Radiocarbon dating showed that the oldest skull in the cache dated back to approximately 5618–5482 BCE, while the youngest was dated to around 5476–5336 BCE. The lack of overlapping date ranges confirmed that the skulls were not gathered all at once but instead added over a period of at least 200 years. Researchers estimated that one skull was added to the collection every decade, suggesting a deliberate, sustained practice of curating these remains for generations.

The criteria for inclusion in the cranial cache remain uncertain. All identified individuals were male, and the absence of children could indicate cultural beliefs about who qualified as an ancestor. Children, possibly viewed as incomplete members of the community, might not have been considered eligible for such practices. The age of the individuals did not appear to play a decisive role, as the cache included people from various age groups. Factors like kinship, societal roles, or manner of death might have influenced selection, though the specifics remain elusive.

The cache was eventually abandoned around 5459 BCE. This marked the end of a long-standing practice, likely due to evolving cultural norms or shifts in spiritual beliefs. One plausible explanation is that the skulls, over time, lost their connection to the living. Without a direct memory link, the individuals represented by the skulls ceased to serve as ancestors, rendering the practice obsolete. Another possibility is that ancestor veneration rituals transitioned to forms that no longer involved physical remains.

This discovery provides valuable context for understanding the complex funerary traditions of Neolithic communities in southern Italy. By analyzing this cranial cache in conjunction with other burial practices in the region, researchers hope to uncover broader patterns and cultural significance. Was this practice unique to Masseria Candelaro, or did similar rituals occur across interconnected communities? What factors determined the specific rites received by individuals after death?

As Dr. Thompson explains, future studies must integrate findings like the cranial cache with other idiosyncratic burial deposits to paint a comprehensive picture of Neolithic spiritual life. This integration could reveal the scale at which these decisions were made—whether they were specific to individual villages or part of larger regional traditions.

The research at Masseria Candelaro offers a profound glimpse into the relationship between the living and the dead during the Neolithic period. These skulls, curated over centuries, serve as a testament to the enduring human need to connect with the past. By honoring their ancestors, these ancient people sought to maintain continuity with those who came before them, preserving their legacies even in death.

Reference: Jess E. Thompson et al, The Use-Life of Ancestors: Neolithic Cranial Retention, Caching and Disposal at Masseria Candelaro, Apulia, Italy, European Journal of Archaeology (2024). DOI: 10.1017/eaa.2024.43

Think this is important? Spread the knowledge! Share now.