When we think of ancient Greek and Roman sculptures, we tend to imagine rows of pristine white marble statues—solemn, timeless, and immaculately smooth. But this iconic image, enshrined in museums and art history books, turns out to be a myth crafted by time and weathering. Science has already rewritten this narrative once, proving that these sculptures were originally painted in vivid hues. Now, thanks to groundbreaking new research from Denmark, we’re learning that they didn’t just dazzle the eyes—they also delighted the nose.

Yes, you read that right. Ancient statues were once not only painted but perfumed. That marble Apollo or Venus wasn’t just meant to look lifelike; it was meant to feel alive in every possible sense. And the scent was part of the experience.

A Living Presence, Not Just Stone

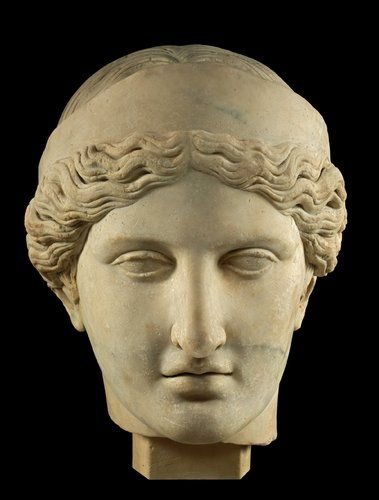

Imagine standing in a grand temple, surrounded by towering columns and the flickering light of oil lamps. Ahead of you looms a statue of a god or goddess, their marble flesh painted in lifelike color. Their eyes seem to follow you, and their garments ripple with painted folds. And then—an unexpected detail—you catch the faint but distinct scent of roses, frankincense, or some exotic perfume wafting from their form. You’re not just looking at a statue. You’re standing in the presence of a divinity.

That’s precisely the experience ancient worshippers might have had, according to Cecilie Brons, an archaeologist and curator at Copenhagen’s Glyptotek museum. Brons’ new study, published in the Oxford Journal of Archaeology, offers fascinating evidence that the ancients didn’t stop at coloring their sacred statues—they perfumed them too.

Rediscovering Forgotten Rituals

Brons embarked on her investigation by diving deep into ancient texts and inscriptions, hunting for clues about how these cult statues were treated and perceived. Roman writers like Cicero, she found, made casual reference to practices that modern readers might easily overlook. For instance, Cicero described a ritual involving a statue of Artemis—known to the Romans as Diana—in the Sicilian city of Segesta. This image of the goddess of the hunt wasn’t just cleaned or polished; it was lovingly anointed with ointments and fragrant oils as part of religious ceremonies.

Elsewhere, on the sacred island of Delos in Greece—home to temples dedicated to Apollo and Artemis—temple records mention the use of rose-scented perfumes to care for statues. These inscriptions didn’t describe the statues as mere objects. They were treated almost like living beings, requiring maintenance, ritual feeding, dressing, and—apparently—perfuming.

“A white marble statue was not intended to be perceived as a statue in stone,” Brons explained in an interview with Danish scientific website Videnskab. “It was supposed to resemble a real god or goddess.”

In other words, ancient statues were not lifeless representations. They were avatars of divine presence. And their visual appearance, texture, scent, and even tactile qualities (many were dressed in fine fabrics and jewelry) were designed to reinforce this sacred illusion.

The Science Behind the Scent

You might be wondering: how do we know these statues were perfumed? Isn’t this just speculation? Brons’ research, while rooted in ancient literature, also ties into archaeological findings. Scientists have previously found microscopic traces of paint on ancient statuary, shattering the long-held myth that these works were conceived in monochrome. Brons adds another sensory layer to this colorful revelation by highlighting textual evidence for the use of oils and perfumes as part of their ritual upkeep.

Although no ancient statue today retains its original fragrance—time and the elements having stripped them bare—this new understanding helps reconstruct how ancient people experienced them. These sculptures were dynamic presences within sacred spaces: glowing with color, gleaming with polished surfaces, and exuding scents that might have mingled with incense and flowers during ritual ceremonies.

And we shouldn’t forget that in the ancient world, perfume wasn’t just cosmetic. Scents had powerful spiritual connotations. Sweet-smelling oils were considered purifying and were thought to attract divine favor. By anointing statues with these fragrant substances, ancient priests and worshippers may have believed they were nurturing the god or goddess inhabiting the image—or enticing their presence to remain.

The Multisensory Experience of Ancient Religion

In today’s museums, we stand behind velvet ropes and gaze at ancient statues as silent, still objects of admiration. But in their original contexts, these works were alive with sensory input. Bright colors made them seem real. Glistening surfaces made them look almost animate. Ritual offerings, chants, incense, and perfume transformed temples into multi-sensory theaters of divine presence.

Brons emphasizes that ancient religious experiences were immersive events. Admiring a statue was “not just a visual experience, but also an olfactory one,” she concluded. Worshippers might have approached a statue offering flowers, smelled the perfume radiating from its surface, and felt the weight of its gaze as if meeting the god or goddess in person.

Why Did We Forget?

So why did the image of white, scentless marble become so deeply entrenched in our imaginations? Blame the Renaissance—and perhaps a touch of Victorian sensibility. Renaissance artists and thinkers revered ancient Greece and Rome, but they prized classical sculpture as pure, austere expressions of form. They encountered the statues stripped of their color and decoration by centuries of exposure to the elements. Their whiteness was mistaken for aesthetic intention rather than erosion.

By the time neoclassical ideals took hold in the 18th and 19th centuries, white marble had become synonymous with “classical beauty.” Colorful statues—and certainly scented ones—didn’t fit the minimalist narrative of timeless, rational perfection. In fact, many 19th-century scholars rejected early evidence of ancient polychromy, dismissing it as barbaric or garish.

It’s only in the past few decades that science has helped resurrect the true complexity of ancient statuary. Modern techniques, such as ultraviolet light analysis and pigment residue testing, have revealed that Greek and Roman statues were often adorned in a riot of colors. Now, studies like Brons’ suggest we need to add another sensory layer to our understanding.

Reimagining the Ancient World

Imagine walking into a sanctuary of Athena, where the goddess stands resplendent in red and gold, her lips painted and eyes inlaid with glass. Perfume wafts from her body—perhaps a musky myrrh or sweet rose oil. The air hums with chanting and the burning of incense. Worshippers approach with offerings, perhaps brushing the statue with oil as an act of devotion. This was the ancient world’s version of a spiritual encounter, a blend of art, ritual, and sensory engagement designed to transport believers closer to the divine.

Cecilie Brons’ research helps bring this vision back to life. It reminds us that ancient statues weren’t silent or cold. They were vibrant, living presences in the eyes—and noses—of those who worshipped them. As science continues to unearth more about ancient religious practices, we may find even more ways the ancients brought their gods to life.

For now, we can appreciate these new revelations for what they are: a deeper understanding of the rich, complex world that existed thousands of years ago. And maybe, just maybe, the next time we stand before an ancient statue in a museum, we’ll imagine not just what it looked like, but what it smelled like too.

Reference: Cecilie Brøns, THE SCENT OF ANCIENT GRECO‐ROMAN SCULPTURE, Oxford Journal of Archaeology (2025). DOI: 10.1111/ojoa.12321