In the vast expanse of the cosmos, where galaxies drift and collide over billions of years, patterns often emerge—structures shaped by gravity, dark matter, and time. Yet every so often, the universe throws a curveball. One such anomaly sits just 2.5 million light-years from Earth: the Andromeda Galaxy, our nearest galactic neighbor. Known for its impending collision with the Milky Way, Andromeda (M31) is now baffling astronomers for a different reason entirely—its bizarre, asymmetric entourage of dwarf galaxies.

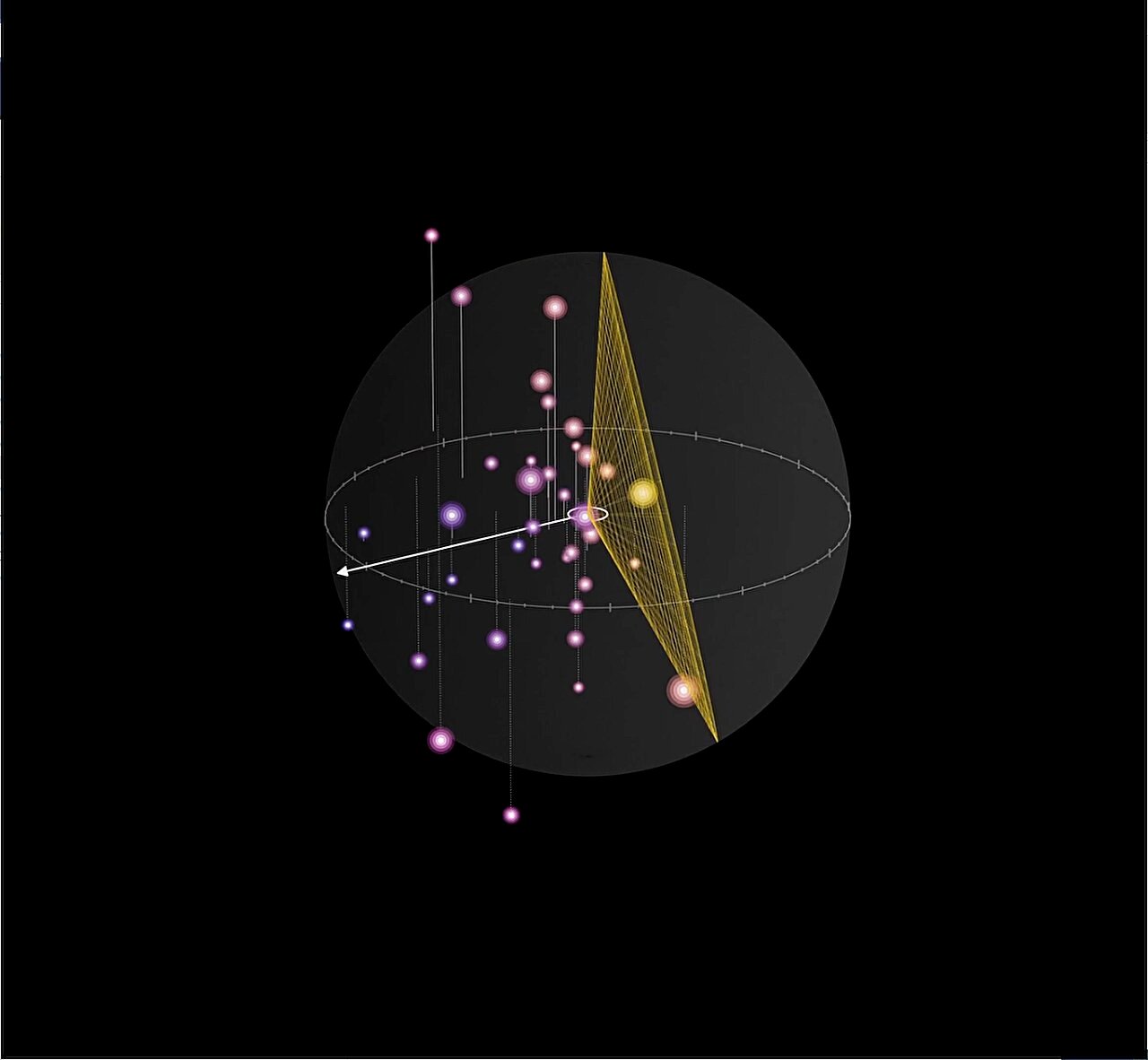

According to recent research published in Nature Astronomy by scientists at the Leibniz Institute for Astrophysics Potsdam (AIP), Andromeda’s satellite galaxies are not arranged as predicted by our best cosmological models. Instead of orbiting in a roughly spherical halo, as the prevailing theories suggest, these smaller galaxies are overwhelmingly concentrated on just one side of Andromeda. It’s a celestial lopsidedness so stark, it’s statistically found in only 0.3% of simulated systems. In a universe governed by chaotic mergers and probabilistic distributions, Andromeda is starting to look like a galactic renegade.

A Universe Built on Patterns—Until Now

The current understanding of cosmic evolution—encapsulated in the standard Lambda Cold Dark Matter (ΛCDM) model—predicts that galaxies grow through mergers. Small, faint galaxies are swallowed over time by larger hosts, and remnants of these mergers, the dwarf galaxies, are expected to be strewn randomly around their massive companions. It’s messy. It’s chaotic. And it’s statistically predictable.

But Andromeda defies that chaos.

Out of 37 known dwarf galaxies orbiting M31, over 80% are clustered within a narrow angular region, just 107 degrees wide, all pointing roughly in the direction of the Milky Way. This zone comprises only 64% of the possible orbital space around Andromeda, yet it’s where nearly every known satellite resides. The rest of the galactic sphere? Almost empty.

“This asymmetry has persisted and even became more pronounced as fainter galaxies have been discovered and their distances refined,” explains Kosuke Jamie Kanehisa, Ph.D. student and lead author of the study. In other words, this is not a statistical fluke due to small sample size. The more we look, the weirder it gets.

Simulations vs. Reality: The Cosmological Disconnect

To understand just how odd this configuration is, Kanehisa and his colleagues turned to cosmological simulations—digital universes that track galaxy formation across cosmic time. They utilized two of the most prominent simulation suites: IllustrisTNG and APOSTLE, which model everything from dark matter halos to star formation and gravitational interactions.

Using customized asymmetry metrics, the team combed through hundreds of simulated galaxies similar to Andromeda. The result? You’d have to sift through more than 300 simulated Andromeda analogs to find even one with a similar degree of one-sided satellite clustering.

“Such a pattern is extremely rare in current cosmological simulations,” says Dr. Marcel S. Pawlowski, co-author and a specialist in galaxy dynamics. “Andromeda is an extreme outlier, defying cosmological expectations.”

Not Just Asymmetric—But Planar, Too

As if the asymmetry wasn’t enough, Andromeda throws another wrench into the machinery of modern cosmology. A subset of its dwarf galaxies—about half—are not just grouped together, but appear to co-orbit in a thin, disk-like structure. Imagine planets orbiting the sun in a flat plane. Now scale that idea up to the galactic level, and you’ll get the rough idea.

This phenomenon, known as the “Plane of Satellites”, has been observed for over a decade, but it was initially brushed aside as coincidence. However, this planar structure has persisted even as new satellites are discovered and their orbital dynamics more precisely measured. Its continued existence, especially when paired with the asymmetric clustering, is downright unsettling to astrophysicists.

Under the standard cosmological model, such an arrangement shouldn’t happen—not on this scale, not with this coherence, and certainly not alongside a spatial asymmetry this severe.

So, What’s Going On?

There are a few possible explanations—none of them completely satisfying.

- An Anomalous Merger History: One hypothesis is that Andromeda had an unusually lopsided merger event in the past, which funneled a cluster of dwarf galaxies into one region. Perhaps a dwarf galaxy group was torn apart and its remnants are now locked in synchronous orbit.

- Large-Scale Cosmic Filaments: The universe is not uniform; galaxies are strung along vast filaments of dark matter and gas. It’s possible that Andromeda’s satellites are being fed through one such filament, aligned toward the Milky Way, explaining the clustering. But this fails to account for the co-orbiting plane.

- Limitations of Current Simulations: Another explanation—perhaps the most unsettling for cosmologists—is that our simulations are missing something fundamental. Stellar feedback, dark matter interactions, or even unknown physics may be required to reproduce these anomalies. If so, our understanding of how galaxies form on small scales may need a significant overhaul.

Implications for Cosmology

The implications of these findings ripple across several domains of astrophysics. If Andromeda’s lopsided satellite structure and orbital plane are not outliers but instead under-sampled norms, then our simulation-based expectations of galaxy evolution could be fundamentally flawed.

Moreover, these structures challenge assumptions about the distribution of dark matter, the formation of galactic halos, and even the behavior of gravity on intergalactic scales. Could it be that dark matter behaves differently in these satellite environments? Or are we glimpsing evidence of unknown forces shaping galactic architecture?

Andromeda’s configuration may even revive interest in alternative gravitational theories like MOND (Modified Newtonian Dynamics), which have occasionally predicted certain satellite structures more successfully than ΛCDM, though these models remain controversial.

What Comes Next?

The hunt is on. Astronomers are now scouring the skies, looking for other galaxy systems with similarly skewed satellite distributions. The upcoming Euclid mission by the European Space Agency is expected to play a crucial role in this effort. With its ability to chart billions of galaxies across cosmic time, Euclid will help determine whether Andromeda is a strange exception—or the tip of an observational iceberg.

Meanwhile, researchers continue to investigate Andromeda’s own history through deep-sky surveys and simulations tailored to match its unique properties. Were there past interactions or collisions that seeded this configuration? Can we reverse-engineer its evolution?

These questions don’t just matter for Andromeda. They matter for the Milky Way, too. Our own galaxy may host a similar, albeit less extreme, structure in its own satellite system—another potential sign that the current model may be overlooking critical small-scale dynamics.

The Lopsided Legacy

In the end, Andromeda’s puzzling satellite arrangement is a cosmic enigma—an elegant defiance of expectation in a universe that usually plays by statistical rules. Whether it’s a rare galactic fluke, the result of an ancient collision, or a symptom of deeper flaws in our cosmological theories, one thing is clear: the universe still has secrets left to whisper.

And as we listen, perhaps with sharper instruments and broader sky surveys, we might find that Andromeda is not an outlier, but the first thread in a larger tapestry waiting to unravel.

References: Kosuke Jamie Kanehisa et al, Andromeda’s asymmetric satellite system as a challenge to cold dark matter cosmology, Nature Astronomy (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41550-025-02480-3

Andromeda’s lopsided galaxy system challenges standard cosmology, Nature Astronomy (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41550-025-02481-2