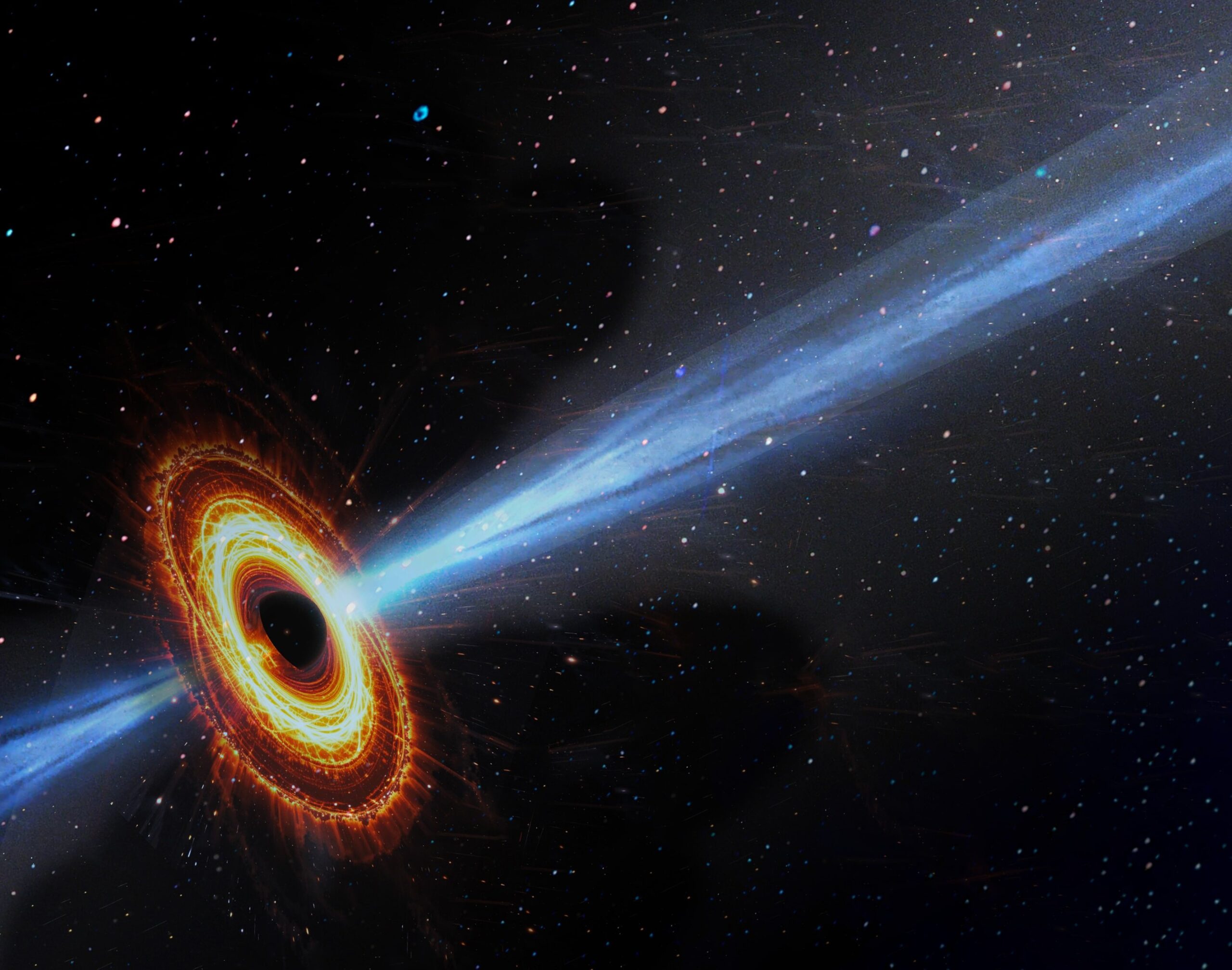

Imagine witnessing a cosmic firehose, spraying streams of plasma at speeds nearing that of light, stretching out across intergalactic space for thousands, even millions, of light-years. These colossal structures, known as relativistic jets, erupt from the hearts of active galaxies, powered by the gravitational behemoths at their centers: supermassive black holes. For decades, scientists have been piecing together how these black holes can launch such powerful jets, and now, an international team of researchers has brought us closer than ever to understanding this extraordinary phenomenon.

Harnessing the extreme precision of the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT), the very same instrument that gave humanity its first-ever image of a black hole in 2019, this global collaboration has taken an unprecedented look at sixteen active galactic nuclei (AGN)—the brilliant, energetic cores of galaxies powered by voracious supermassive black holes. By observing these cosmic engines in multiple wavelengths and comparing them with earlier observations, the team has begun to rewrite our understanding of how jets accelerate and evolve as they escape the grip of a black hole’s gravity.

Their findings, published in Astronomy & Astrophysics, offer a fascinating and more complex view of jet behavior than previously imagined.

Peering into the Heart of Galaxies: The Power of the Event Horizon Telescope

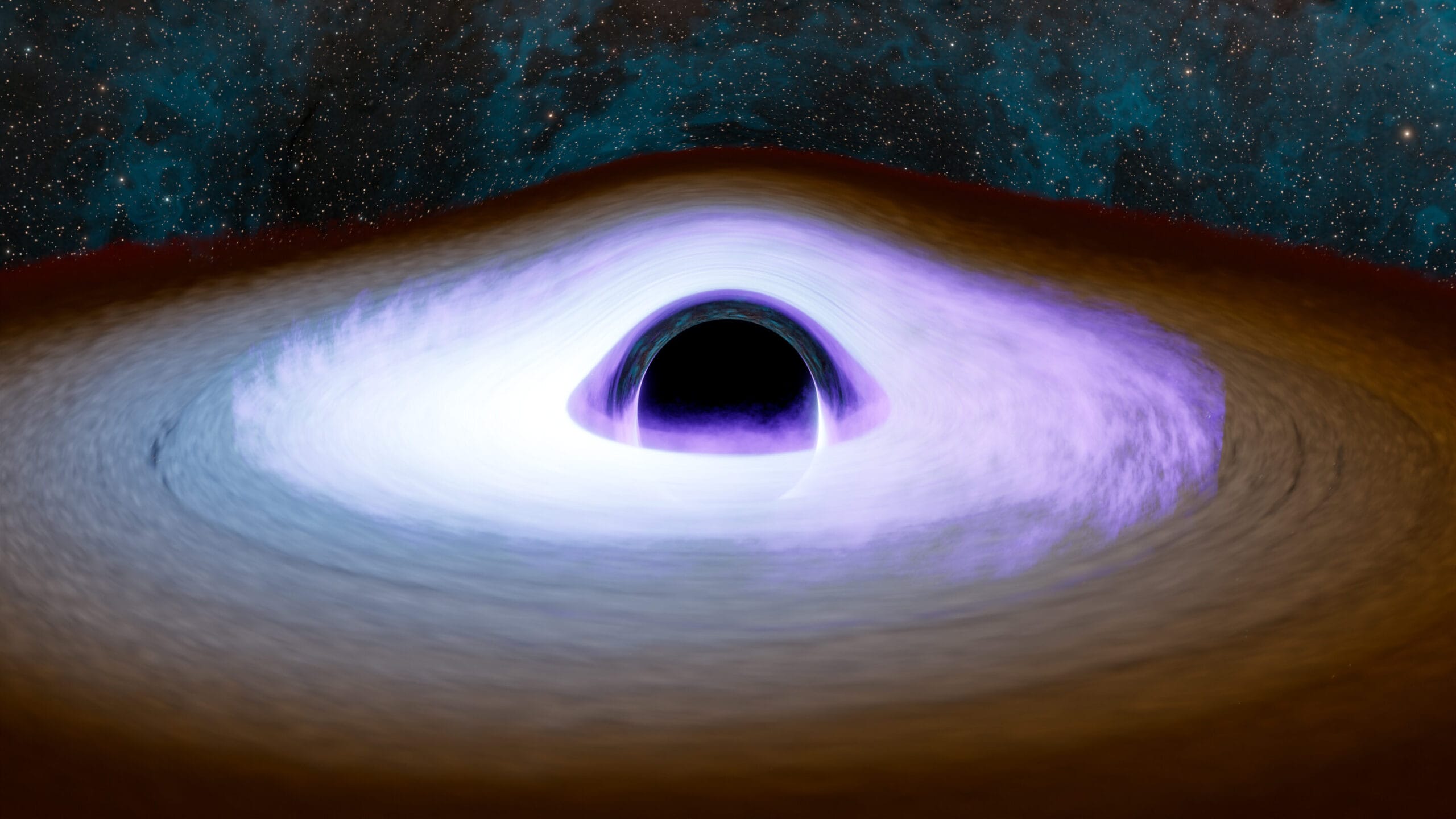

At the center of many galaxies lies an AGN, where a supermassive black hole devours gas and dust, heating this matter to incredible temperatures and igniting the release of intense radiation. In some of these AGN, not all of the material is consumed. Instead, a fraction is funneled into narrow, high-speed jets of plasma that blast outward, defying gravity and tearing across space at nearly the speed of light.

Understanding how these jets are launched and accelerated has remained one of astrophysics’ biggest challenges. To answer this cosmic riddle, scientists need to see incredibly fine details—details that until recently were obscured by distance, scale, and technology.

That’s where the Event Horizon Telescope comes in. A virtual Earth-sized telescope made by combining radio observatories from around the globe through a technique called very long baseline interferometry (VLBI), the EHT offers a resolution so sharp it’s like spotting an orange on the Moon from Earth.

In 2017, during its first major observing campaign, the EHT focused not only on its two headline targets—Sagittarius A*, the black hole at the center of our Milky Way, and M87*, the giant black hole at the heart of the galaxy Messier 87—but also on a sample of sixteen other AGN. By pushing the limits of observational astronomy, the EHT team took an unprecedented look at regions of space much closer to the black holes where these relativistic jets are born.

A Global Effort: Scientists from Bonn to Granada Lead the Charge

This groundbreaking study was spearheaded by an international team of astrophysicists from the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy (MPIfR) in Bonn, Germany, and the Institute of Astrophysics of Andalusia (IAA-CSIC) in Granada, Spain. Leading the effort was Jan Röder, whose team set out to tackle fundamental questions about how jets accelerate and the role of magnetic fields in their formation.

“We were able to look closer than ever before, thanks to the EHT,” said Röder. “But just as important was comparing these cutting-edge observations with those gathered by previous instruments, such as the Very Long Baseline Array (VLBA) and the Global Millimeter VLBI Array (GMVA), which study jets at larger scales. That comparison allowed us to see how jets evolve over vast distances—from near the black hole’s event horizon all the way out into interstellar space.”

The Quest to Understand Jet Acceleration and Magnetization

At the core of the team’s research was a question that’s puzzled scientists for decades: How do these plasma jets accelerate to relativistic speeds? And how do they maintain their structure over distances that can span galaxies?

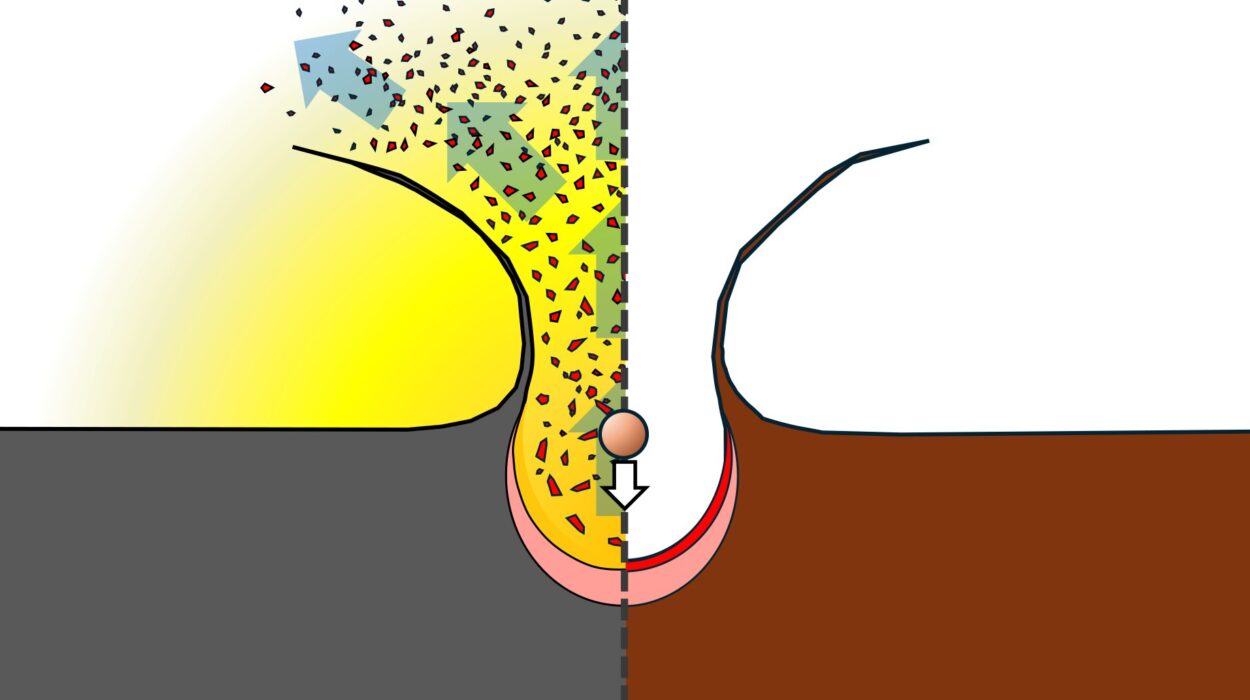

The standard model for jets assumes they have a conical shape, with plasma flowing outward at a constant velocity. As the jets travel away from the black hole, both the strength of their magnetic fields and their particle densities decrease. Based on these ideas, astrophysicists have made predictions about how jets should behave—and how they should look to our telescopes.

But what Röder and his colleagues discovered challenges this traditional thinking.

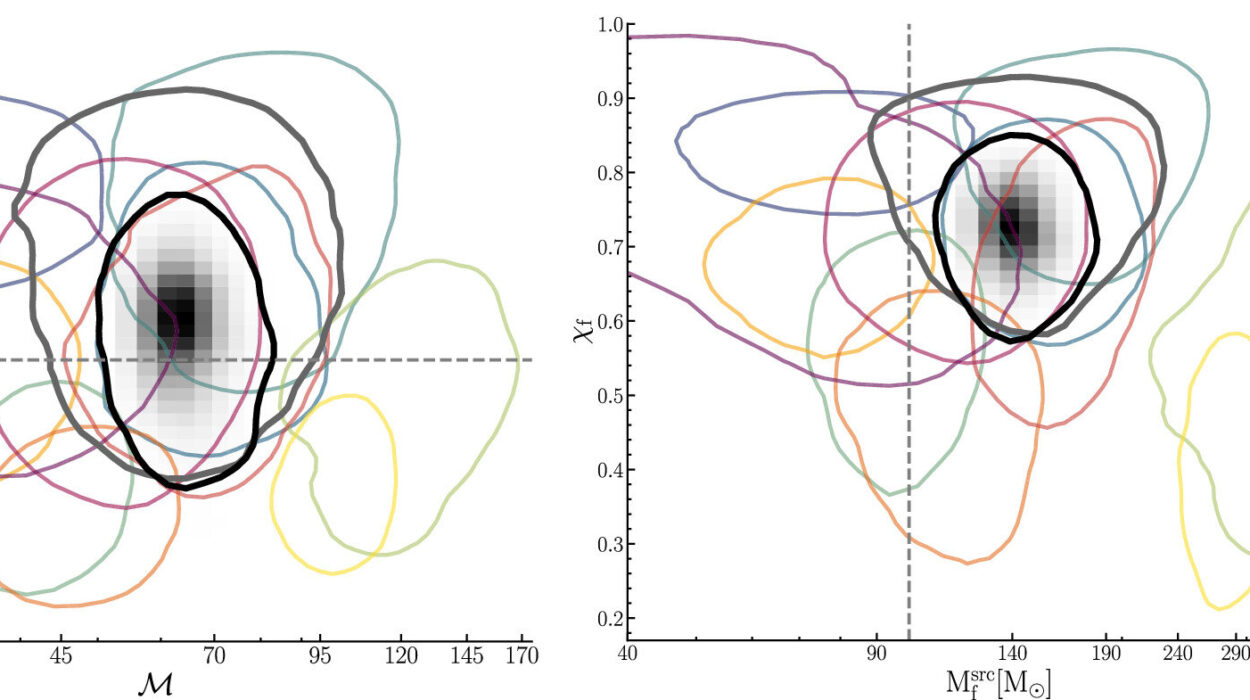

By analyzing their sample of sixteen AGN across different frequencies and angular scales, the researchers noticed something striking: the brightness of the jets—measured by their brightness temperature—tended to increase as the jet plasma traveled farther from the black hole. This suggests that, contrary to previous assumptions, the jets are accelerating as they move away from their central engines.

“This was a real surprise,” said Röder. “The simplest models predicted a steady flow, but our observations strongly indicate continued acceleration, even many light-years from the black hole.”

Project co-leader Maciek Wielgus, based at IAA-CSIC, emphasized the importance of studying a large, diverse sample. “By focusing on sixteen AGN instead of just one or two, we reduced the influence of any peculiarities unique to individual sources. This broader approach gives us a more general view of how jets behave.”

Rethinking Jet Dynamics: The Role of Geometry and Magnetic Fields

But why are these jets accelerating? Is the plasma itself speeding up? Or is there another explanation?

One possibility lies in geometry. If a jet bends slightly and points more directly at Earth, the motion could appear faster due to relativistic effects—a kind of cosmic optical illusion. But this alone doesn’t seem to account for all the observations.

Instead, the team believes that magnetic fields likely play a significant role in both launching and accelerating jets. The interplay between magnetic energy and kinetic energy—how tightly the jets are magnetized—could drive these powerful streams of plasma to higher and higher speeds.

“This basic model of jets being simple conical outflows doesn’t hold up in many cases,” Röder explained. “The structure and dynamics of these jets are intricate. We’re only beginning to untangle the complex forces at play.”

From the EHT to the GMVA: Bridging the Scale Gap

Eduardo Ros of MPIfR, who also serves as the European Scheduler of the Global Millimeter VLBI Array, highlighted the critical role of intermediate-scale observations. The GMVA, operating at a wavelength of 3.5 millimeters, bridges the gap between the ultra-fine resolutions of the EHT and the wider fields of view offered by the VLBA.

“These different instruments give us a layered view of jet evolution,” Ros said. “For example, in the famous galaxy M87, we’ve seen this layered approach reveal critical insights about how jets propagate from the black hole outward. This work is like assembling a cosmic jigsaw puzzle, with each observatory contributing vital pieces.”

A New Frontier in Understanding Active Galactic Nuclei

Active galactic nuclei are among the most luminous and energetic phenomena in the universe. Powered by black holes millions to billions of times more massive than our Sun, AGN unleash torrents of radiation and relativistic plasma jets that can influence the evolution of their host galaxies and even entire clusters.

The jets are more than spectacular cosmic fireworks; they are thought to play a key role in regulating star formation by heating or expelling interstellar gas and dust. Understanding their behavior helps explain not only the life cycles of galaxies but also the broader story of cosmic evolution.

To get there, scientists need observations with ever-increasing precision. The EHT, already a scientific marvel, is continuously expanding. New telescopes joining the network and advancements in technology will sharpen its view even further.

“These studies mark the beginning of a new era,” said Röder. “With the expanding EHT array and next-generation instruments, we’ll be able to probe deeper into the physics of jets, exploring how energy and matter flow through some of the most extreme environments in the universe.”

The Power of Global Collaboration and Future Prospects

J. Anton Zensus, director at MPIfR and founding chair of the EHT collaboration, reflected on the broader significance of these findings. “This work demonstrates what we can achieve through international cooperation, cutting-edge technology, and persistent scientific inquiry,” he said. “It’s a testament to the power of global partnerships.”

Zensus and his colleagues are optimistic about the future. The EHT’s planned upgrades and the development of new networks, such as the next-generation Event Horizon Telescope (ngEHT), promise to deepen our understanding of black holes, jets, and the fundamental forces shaping the cosmos.

“Each discovery brings new questions,” said Zensus. “That’s the beauty of science. As we look closer and with greater clarity, we find more mysteries waiting to be solved.”

Conclusion: Unlocking the Mysteries of Cosmic Jets

The study of relativistic jets from supermassive black holes is a window into some of the universe’s most powerful and mysterious processes. Thanks to the Event Horizon Telescope and the collaborative work of scientists across the globe, we are beginning to unlock the secrets of how these cosmic engines work.

These findings are not just incremental advances—they’re reshaping the landscape of astrophysics. As we refine our tools and expand our reach, we stand at the threshold of new discoveries that could rewrite our understanding of black holes, galaxies, and the very nature of space and time itself.

For now, one thing is certain: the universe has many more secrets to reveal, and humanity is only just beginning to listen.

Reference: Jan Röder et al, A multifrequency study of sub-parsec jets with the Event Horizon Telescope, Astronomy & Astrophysics (2025). DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/202452600