Imagine one peaceful evening, you look up at the sky. The stars are twinkling, as they always do. But then, suddenly, a brilliant, blinding point of light erupts where there was none before. It’s brighter than the full Moon, outshining every star in the sky. You can even see it in broad daylight. Over the following days, it glows ominously, refusing to fade.

What you’re witnessing is the spectacular death of a massive star—a supernova. These titanic explosions are so powerful they can briefly outshine entire galaxies. They create elements that make up our bodies and planets. Without them, we wouldn’t be here. But these cosmic fireworks, as awe-inspiring as they are, have a dark side. If one went off too close to Earth, could we survive?

This question might seem like pure science fiction, but it’s a real and pressing concern for astronomers and astrobiologists. Supernovae have reshaped life on Earth before—possibly causing mass extinctions—and they could do it again. But how close is too close? What would happen? And are there any ticking time bombs near us?

Let’s take a journey through the science of supernovae, their devastating power, and what humanity can do—if anything—to survive one.

What Is a Supernova, Anyway?

Before we dive into how dangerous they are, we need to understand what a supernova actually is. In short, it’s the explosive death of a star. But not just any star. Only the biggest and most massive stars—those with at least eight times the mass of our Sun—can go supernova in the most violent way.

Here’s a breakdown:

The Life of a Massive Star

Stars are gigantic nuclear fusion reactors. They spend most of their lives turning hydrogen into helium in their cores. This fusion creates energy, which pushes outward and balances the gravitational pull trying to crush the star inwards.

But eventually, the star runs out of hydrogen fuel. It starts fusing heavier and heavier elements—helium into carbon, carbon into oxygen, oxygen into silicon, and so on—all the way to iron. And here’s the catch: fusing iron doesn’t release energy; it costs energy. So once iron builds up in the core, the star is in serious trouble.

Gravity wins. The core collapses in an instant, and the outer layers fall inward, smashing into the core and bouncing outward in a cataclysmic explosion: a core-collapse supernova.

Types of Supernovae

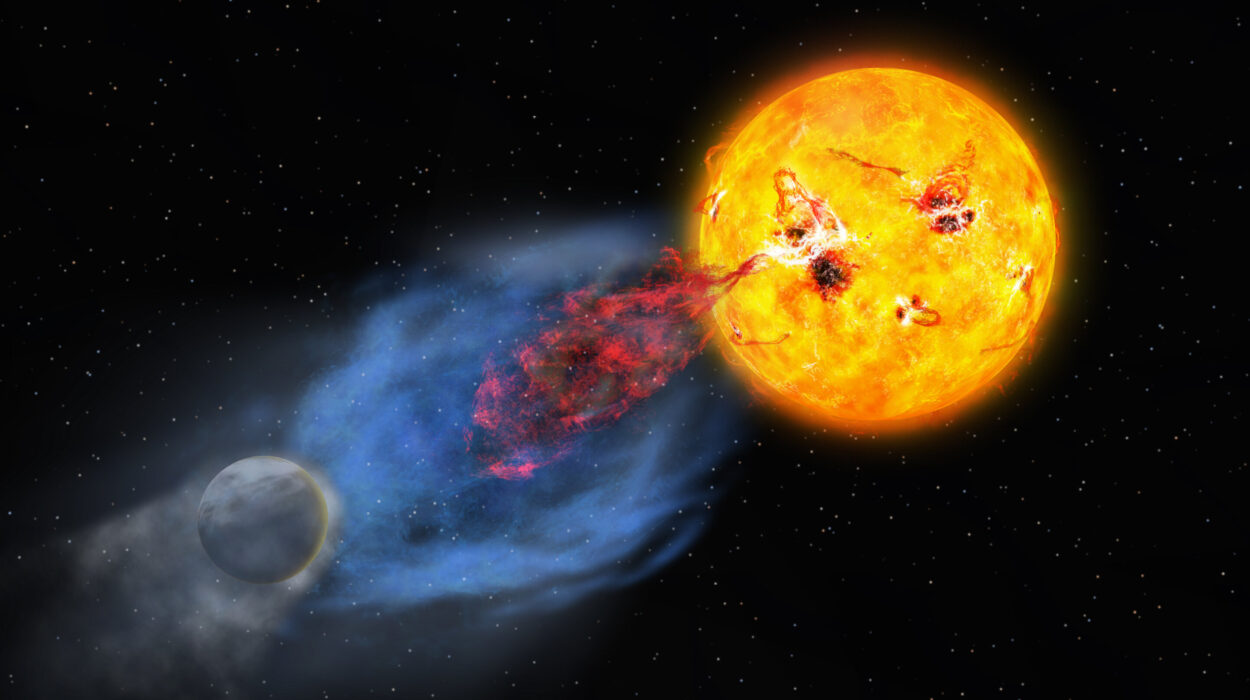

- Type II Supernovae: Result from the collapse of massive stars. They leave behind neutron stars or black holes.

- Type Ia Supernovae: These happen in binary star systems where a white dwarf star siphons off material from a companion until it can’t handle the pressure and detonates in a thermonuclear explosion.

Both types are intensely powerful, but for Earth, the most dangerous are nearby Type II and Type Ib/c supernovae.

The Power of a Supernova: Cosmic Violence on an Unimaginable Scale

Supernovae are violent beyond human comprehension. In a few moments, a supernova releases more energy than our Sun will emit in its entire 10-billion-year lifetime. The explosion sends shockwaves of matter hurtling into space at tens of thousands of kilometers per second. It generates lethal radiation and floods the cosmos with high-energy particles.

So, why does that matter to Earth?

Because space is not as empty as it seems. Energy and matter from a supernova don’t just dissipate harmlessly. They travel. And if we happen to be in their path, Earth could be in serious trouble.

The Kill Radius: How Close Is Too Close?

Astronomers have crunched the numbers, and the dangerous distance depends on what kind of supernova it is. But there’s a general rule of thumb:

- Within 10 light-years (3 parsecs): Instant doom. We’d be toast. Literally.

- Within 30 light-years (10 parsecs): Still very bad. The effects could strip our planet’s atmosphere and doom life as we know it.

- Within 50-100 light-years: We might survive, but life would suffer. There could be mass extinctions, climate upheavals, and long-term radiation hazards.

For perspective, 10 light-years is about 60 trillion miles away. That sounds distant, but on a cosmic scale, it’s right next door.

What Happens If a Supernova Goes Off Too Close?

Let’s get detailed about what would happen if a supernova exploded dangerously close to Earth.

1. A Blinding Flash

First, we’d see a sudden, blindingly bright light in the sky. If it was close enough, it would be as bright as a full Moon, even in the day. It might stay that bright for weeks, bathing Earth in intense visible and ultraviolet light.

2. A Deadly Burst of Radiation

Within hours or days, the real danger arrives: gamma rays and X-rays. These high-energy photons would blast through the solar system and slam into Earth’s upper atmosphere.

Gamma rays are incredibly destructive. They can ionize atoms, breaking molecular bonds and stripping electrons from atoms in the upper atmosphere. This process creates nitrogen oxides that destroy the ozone layer. Without ozone, Earth is exposed to unfiltered ultraviolet radiation from the Sun. That would devastate life on land and in shallow water, where most life exists.

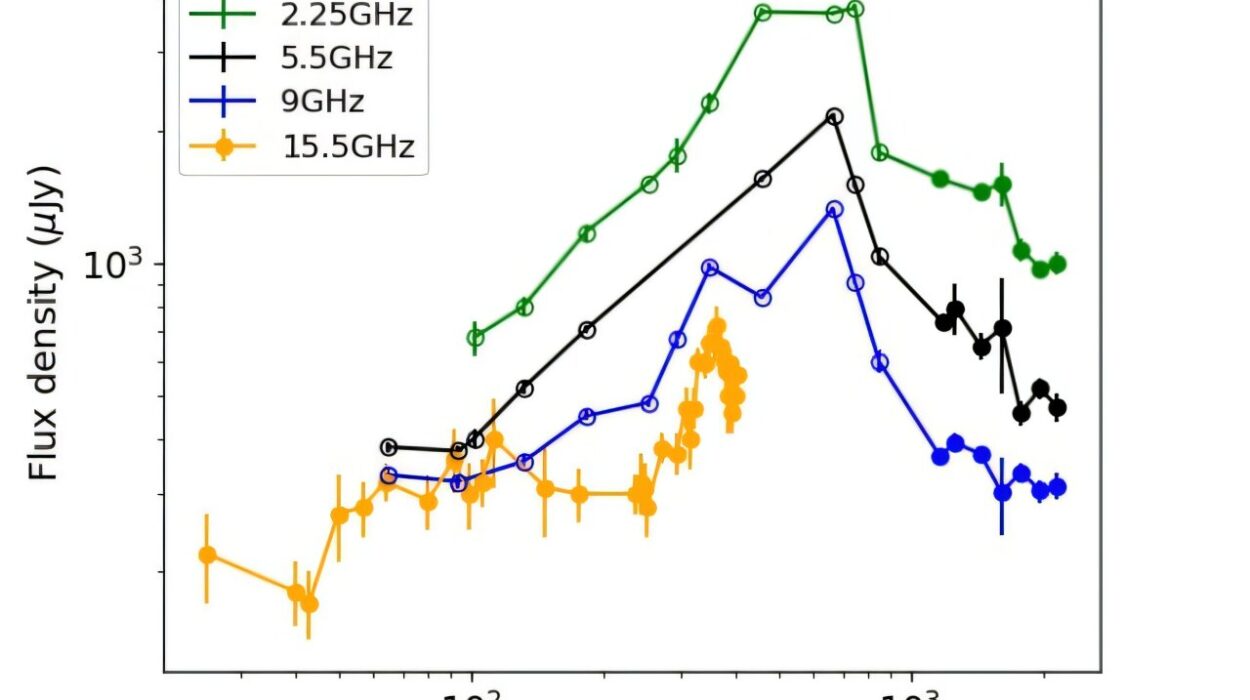

3. Cosmic Rays: The Long-Term Killer

Next come cosmic rays—high-energy atomic nuclei traveling at nearly the speed of light. These arrive more slowly, over hundreds or thousands of years. They bombard Earth’s atmosphere, creating secondary radiation, including muons that can penetrate deep into the Earth’s surface and oceans.

Cosmic rays would increase background radiation levels significantly. Living creatures exposed to elevated radiation for long periods would suffer increased cancer rates, genetic mutations, and reproductive problems.

4. Climate Chaos

A nearby supernova could also change Earth’s climate. Increased cosmic ray flux could trigger cloud formation, potentially cooling the planet. If severe enough, it could lead to global cooling, even a “cosmic winter” scenario.

On the flip side, destruction of the ozone layer could lead to global warming and increased surface UV radiation, causing ecological collapse.

5. Mass Extinctions

Evidence suggests that supernovae have triggered mass extinctions on Earth in the past. If a nearby star went supernova today, many forms of life would struggle to survive. The radiation and climate disruptions could wipe out species, disrupt ecosystems, and cause widespread collapse of food chains.

Has Earth Survived Supernovae Before?

Yes! There’s growing evidence that Earth has experienced the effects of nearby supernovae in its past. For example:

The Late Pleistocene Supernovae

Scientists have found isotopes of iron-60 in ocean sediments, which shouldn’t be here unless they came from a nearby supernova. Iron-60 is made in supernova explosions and has a half-life of about 2.6 million years. Its presence suggests that multiple supernovae went off within 100 light-years of Earth, around 2 to 3 million years ago.

While we don’t know if these events caused extinctions, they may have contributed to climate changes and shifts in life on Earth at the time.

The Ordovician-Silurian Extinction

Some scientists speculate that a gamma-ray burst or supernova might have triggered this mass extinction about 450 million years ago, by damaging the ozone layer and causing glaciation.

Which Stars Should We Worry About?

Fortunately, not all stars are candidates for supernovae. Only the biggest and most massive stars can explode this way. The good news? Most of these stars are pretty far away. But a few nearby suspects keep astronomers awake at night.

1. Betelgeuse (640 Light-Years Away)

Betelgeuse, a red supergiant in the constellation Orion, is on death’s doorstep. It’s expected to go supernova sometime in the next 100,000 years. But at 640 light-years away, it’s far enough that Earth is safe. When it blows, it’ll be a spectacular sight—but not a danger.

2. Antares (550 Light-Years Away)

Antares is another red supergiant. It’s also destined for a supernova, but it’s too far to threaten Earth.

3. Rigel (860 Light-Years Away)

Rigel is a blue supergiant, and it will likely go supernova as well. Again, it’s safely distant.

4. Wolf-Rayet Stars

These are extremely massive stars in their final phases of life. They’re rare but dangerous because they can produce gamma-ray bursts (GRBs)—ultra-powerful jets of energy that could do immense damage. Fortunately, no Wolf-Rayet stars within 5,000 light-years are pointed directly at us.

5. The Scariest Star: WR 104 (7,500 Light-Years Away)

WR 104 is a Wolf-Rayet star that has a jet pointed in Earth’s general direction. If it produces a GRB when it goes supernova, we might feel it. But it’s so far away that most astronomers think it’s unlikely to hurt us.

What About the Sun?

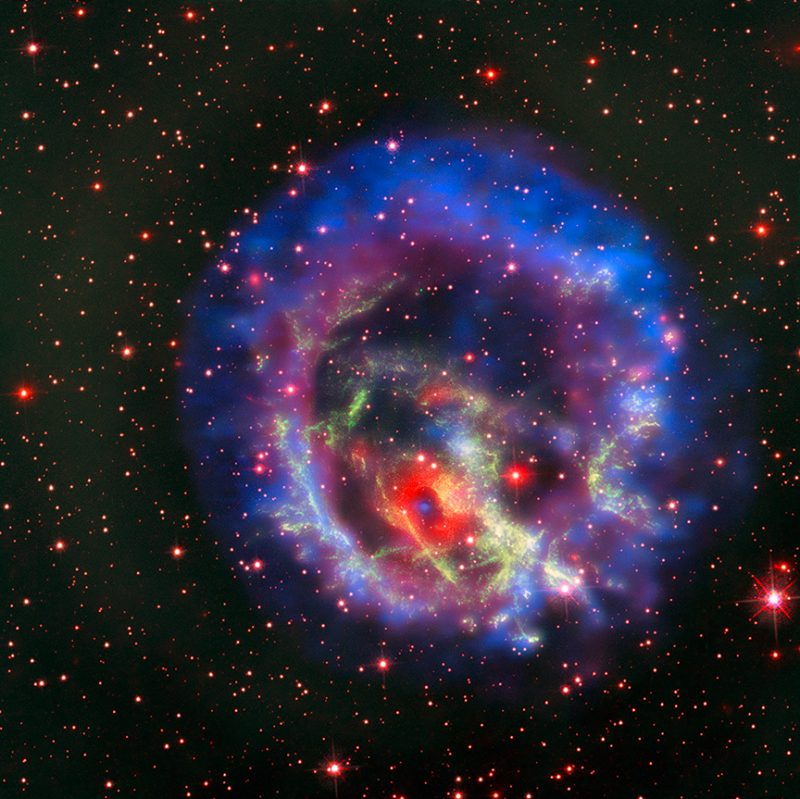

Don’t worry—the Sun isn’t massive enough to go supernova. In about 5 billion years, it will swell into a red giant and shed its outer layers, forming a beautiful planetary nebula and leaving behind a white dwarf. No explosions here.

What Could We Do to Survive a Nearby Supernova?

This is the billion-dollar question: could we do anything to protect ourselves from a deadly supernova?

1. Early Warning Systems

Astronomers keep a close eye on nearby massive stars. Telescopes around the world and in space monitor their behavior. If a star looks unstable, we might get advance warning of an impending explosion—days, weeks, or maybe even years.

Neutrino detectors, like Japan’s Super-Kamiokande, could give us an early heads-up hours before a supernova’s shockwave reaches us.

2. Protecting the Atmosphere

If we knew the ozone layer would be destroyed, we could try to mitigate UV radiation by building underground habitats or shielded greenhouses. We might deploy aerosols in the atmosphere to block UV light or develop materials to filter sunlight.

3. Space-Based Shields?

In theory, gigantic magnetic shields or radiation-blocking satellites could protect Earth from cosmic rays. But these are still in the realm of science fiction. The energy and resources needed would be astronomical.

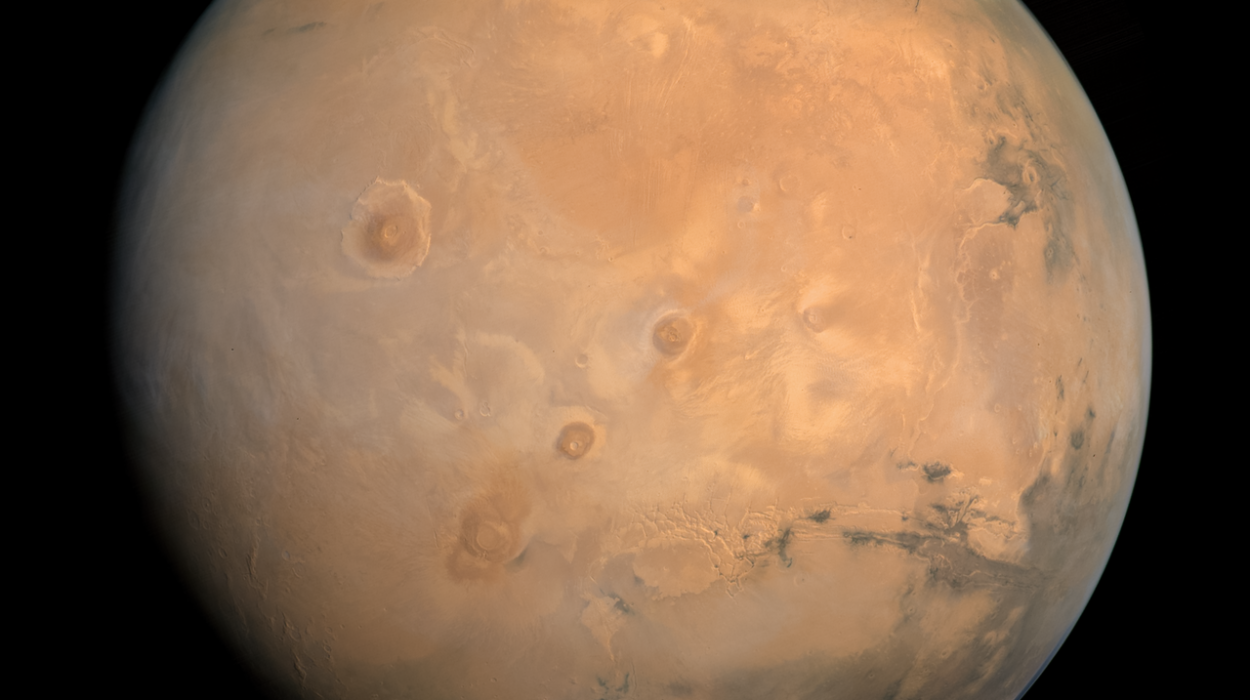

4. Colonizing Other Worlds

In the long run, spreading humanity beyond Earth is the best insurance policy. If we have colonies on Mars, the Moon, or distant planets, we reduce the risk of extinction from any single catastrophe—whether it’s a supernova, asteroid, or something else.

Conclusion: The Ultimate Cosmic Wildcard

Supernovae are among the universe’s most destructive forces, but they are also creators. They forge the heavy elements that make up planets, life, and even the iron in our blood. Without them, we wouldn’t exist. Yet, their explosive power makes them dangerous neighbors.

The good news? The odds of a supernova going off close enough to Earth to cause real harm in our lifetimes are very low. The bad news? Over millions of years, the threat is real—and unpredictable.

For now, all we can do is watch the skies, learn more about our stellar neighbors, and prepare for the distant future. If nothing else, understanding these cosmic cataclysms reminds us of our fragile place in the universe—and how much we depend on our thin blanket of atmosphere and the stability of our tiny blue world.

The next time you look up at the night sky and spot Orion’s shoulder—Betelgeuse—take a moment to appreciate the power of the stars and the delicate balance of life here on Earth. The cosmos giveth, and the cosmos taketh away. But with knowledge, science, and a bit of cosmic luck, we might just survive whatever the universe throws our way.