For the first time in history, researchers have uncovered definitive chemical evidence that wine was consumed in the legendary city of Troy. This discovery, published in the April edition of the American Journal of Archaeology, confirms a long-standing hypothesis proposed by Heinrich Schliemann, the 19th-century archaeologist who first unearthed the ruins of Troy. Even more intriguingly, the study reveals that wine drinking was not limited to the elite but was a common indulgence among the general population.

The groundbreaking research was conducted by teams from the Universities of Tübingen, Bonn, and Jena, and their findings offer a fascinating glimpse into the social and cultural fabric of Bronze Age Troy. By analyzing ancient drinking vessels, the researchers have not only substantiated Homeric descriptions but have also deepened our understanding of daily life in one of history’s most famous cities.

A Homeric Tradition Confirmed

The Iliad, Homer’s epic account of the Trojan War, is filled with references to wine as a central part of feasting and divine rituals. In Book 1 of the Iliad, the god Hephaestus serves wine to the Olympian gods in a ceremonial manner:

“Hephaestus spoke, then stood up, passed a double goblet across to his dear mother… As he spoke, the white-armed goddess Hera smiled. She reached for her son’s goblet. He poured the drink, going from right to left, for all the other gods, drawing off sweet nectar from the mixing bowl.”

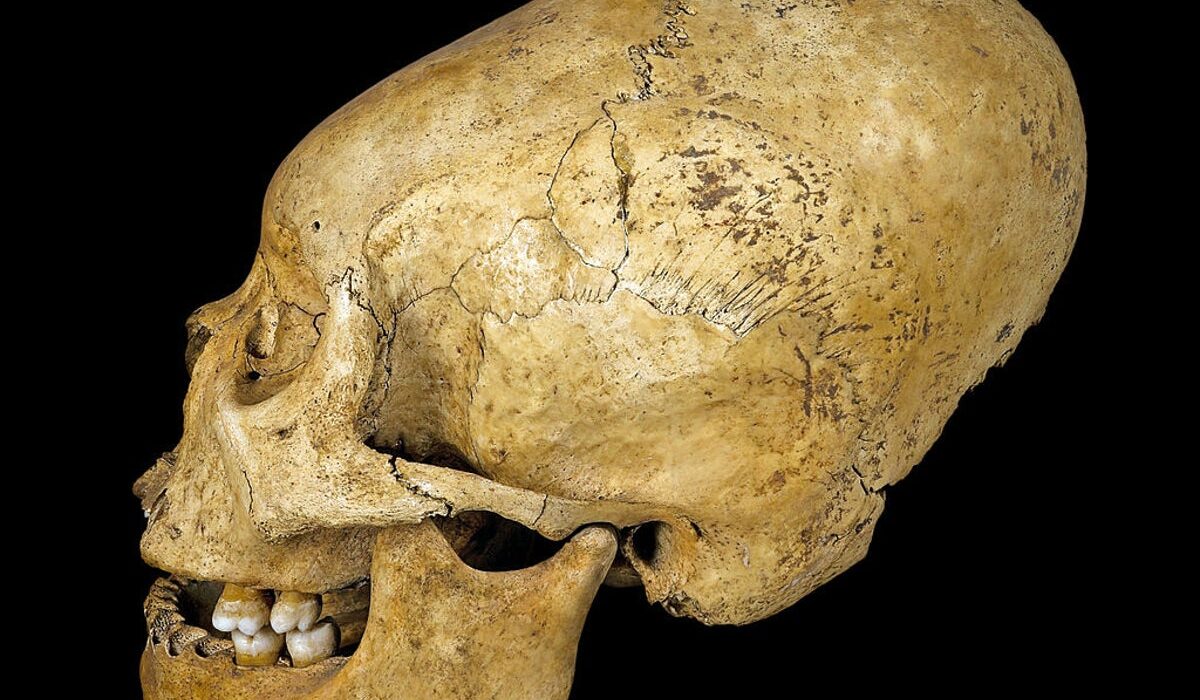

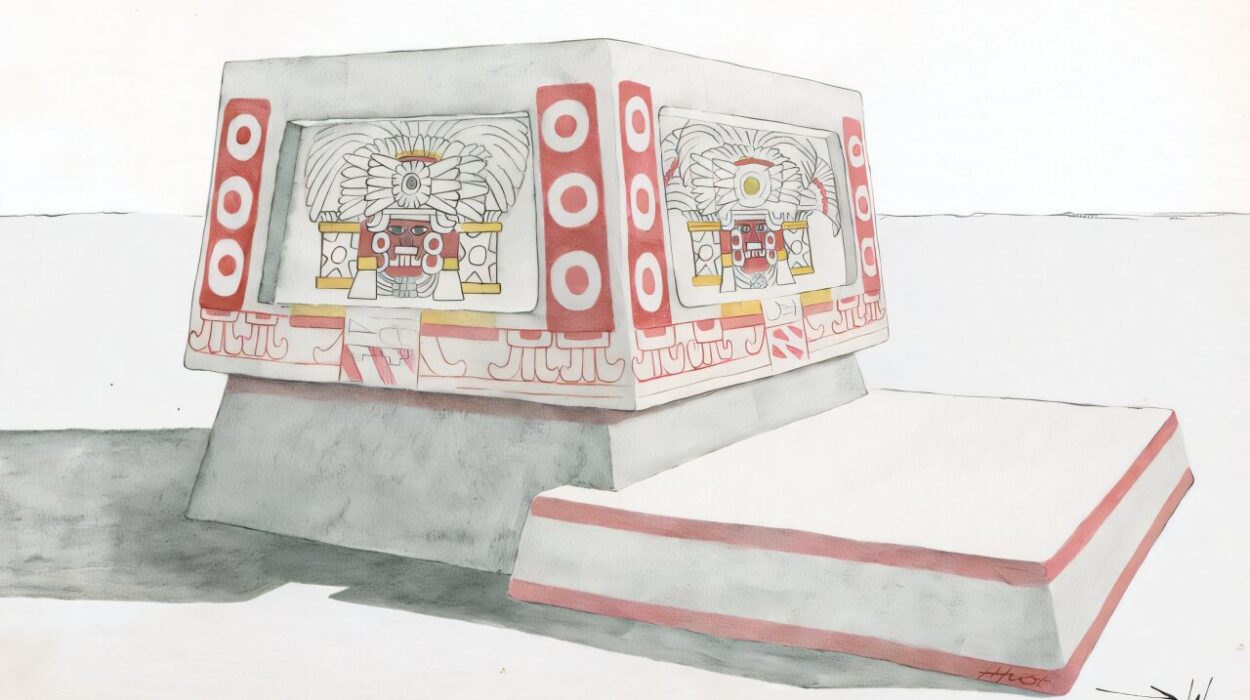

This passage describes the use of a special drinking vessel, the depas amphikypellon—a type of goblet known to archaeologists simply as the depas. These vessels, made of slender clay, feature two handles and a pointed base, making them distinctive and easily recognizable. They vary in size from 12 to 40 centimeters and can hold between 0.25 and 1 liter of liquid.

More than a hundred such goblets have been found in Troy alone, dating back to between 2500 and 2000 BCE. They are also scattered across the Aegean, Asia Minor, and Mesopotamia, suggesting extensive cultural and trade links. Given their prevalence and Homeric descriptions, Schliemann had speculated that these goblets were used for wine-drinking at feasts, but no direct evidence had ever confirmed this—until now.

Unveiling the Chemical Proof of Wine Consumption

To settle the long-debated question of whether these goblets contained wine or just grape juice, scientists turned to advanced chemical analysis. Dr. Stephan Blum, a co-author of the study from the University of Tübingen, emphasized the importance of this investigation:

“Heinrich Schliemann already conjectured that the depas goblet was passed around at celebrations—just as described in the Iliad. But until now, there was no scientific proof.”

To extract this proof, researchers examined samples from a depas goblet housed in the classical archaeology collection of the University of Tübingen. Maxime Rageot from the University of Bonn milled a tiny 2-gram sample from two fragments of Schliemann’s original finds. These samples were then heated to 380°C and analyzed using gas chromatography (GC) and mass spectrometry (GC-MS).

The results were unmistakable: traces of succinic and pyruvic acids were detected—compounds that only form when grape juice undergoes fermentation. This provided the first-ever direct chemical evidence that the depas goblets were indeed used for drinking wine.

“Now we can state with confidence that wine was actually drunk from the depas goblets and not just grape juice,” says Rageot.

Wine for the Commoners: A Surprise Revelation

Wine was the most expensive drink of the Bronze Age, often associated with religious rituals, political alliances, and elite feasting. Given the luxurious nature of wine, archaeologists had long assumed that it was consumed exclusively by the upper classes of Troy. The depas goblets, found mainly in palace and temple complexes, reinforced this belief.

However, the researchers expanded their analysis to include more humble drinking vessels—everyday cups found in the outer settlement of Troy, far beyond the citadel. The results were astonishing: these common cups also contained traces of wine.

“We’ve also chemically studied ordinary cups that were found in the outer settlement of Troy and therefore outside the citadel. These vessels also contained wine,” says Blum. “So it is clear that wine was an everyday drink for the common people too.”

This finding fundamentally changes our perception of social life in ancient Troy. Instead of being an exclusive luxury, wine was widely accessible, enjoyed by both rulers and laborers alike. This suggests that wine was not just a ceremonial or high-status beverage but an integral part of Trojan daily life.

Troy’s Role in the Ancient Wine Trade

The discovery that both elites and commoners drank wine in Troy raises important questions about the city’s role in the ancient wine trade. Wine production in the Bronze Age required significant agricultural resources, fermentation knowledge, and long-distance trade networks to distribute it across regions.

Troy, strategically positioned near the Dardanelles—a crucial maritime passage between the Aegean and the Black Sea—was ideally located for trade. The presence of wine residues in commoner households indicates that either local vineyards existed to sustain the demand, or that wine was imported in large quantities from other parts of the ancient world.

Furthermore, the presence of depas goblets beyond Troy—across Anatolia, the Aegean, and even Mesopotamia—suggests that the drinking culture associated with these vessels was widespread. Perhaps wine-drinking rituals in Troy were not unique but part of a broader cultural tradition that linked different civilizations through shared feasting practices.

Rewriting the Story of Troy

This discovery is yet another piece in the complex puzzle of Troy’s history, adding new dimensions to our understanding of its society. The long-standing narrative of Troy as a city primarily known for its military conflicts—especially the legendary Trojan War—now expands to include a vibrant, wine-drinking culture that permeated all social classes.

Professor Dr. Karla Pollmann, President of the University of Tübingen, highlights the significance of this breakthrough:

“Research into Troy has a long tradition at the University of Tübingen, and I am delighted that we have been able to add another piece to the puzzle revealing the picture of Troy.”

Although the University of Tübingen led the excavations at Troy from 1987 to 2012, the analysis of these findings continues. This latest discovery serves as a reminder that even well-explored archaeological sites still hold secrets waiting to be uncovered.

Conclusion: A New Perspective on Ancient Drinking Culture

The confirmation that Trojans, from rulers to commoners, enjoyed wine adds a fresh and deeply human perspective to our image of the city. Instead of just being the stage for an epic war, Troy was a lively, interconnected, and socially diverse city where people gathered to drink, celebrate, and share stories—perhaps even the very tales that inspired Homer’s Iliad.

This discovery is more than just about wine—it is about people, their traditions, and the way they lived their daily lives thousands of years ago. By revealing that wine was not merely a luxury but a common staple, researchers have provided a richer, more nuanced understanding of ancient Troy.

And so, with each new discovery, history drinks deeper from the well of knowledge, revealing a world that, though ancient, still speaks to us across the ages.

Reference: Stephan W.E. Blum et al, The Question of Wine Consumption in Early Bronze Age Troy: Organic Residue Analysis and the Depas amphikypellon, American Journal of Archaeology (2025). DOI: 10.1086/734061