In an extraordinary discovery that sheds new light on the history of early Spanish exploration in North America, independent researchers in Arizona have unearthed a bronze cannon linked to the 1539–1542 expedition led by Francisco Vázquez de Coronado. The artifact, which is the oldest firearm ever found in the continental United States, provides a unique glimpse into the weaponry used by the Spanish conquistadors as they ventured into the American Southwest. This discovery not only enriches our understanding of the Coronado expedition but also reveals the complex interplay of exploration, warfare, and cultural encounters between the Spanish and the Native American populations of the time.

The Coronado Expedition: Quest for Gold and Glory

The story of Francisco Vázquez de Coronado’s expedition is one of ambition, failure, and historical significance. In the early 16th century, rumors of vast riches in the lands north of Mexico—particularly the fabled Seven Cities of Cíbola—captured the imagination of Spanish explorers. These reports, fueled by earlier accounts of conquistadors and by Fray Marcos de Niza’s descriptions of wealth beyond the northern frontier, compelled Viceroy Antonio de Mendoza to commission an expedition to explore and claim these new territories.

Coronado, a nobleman who had mortgaged his wife’s possessions and borrowed heavily to finance the journey, was appointed to lead the expedition. His mission was not only to uncover the riches described by the reports but also to assert Spanish dominance over the region, claim new lands, and expand the influence of the Spanish Crown. He assembled an army consisting of 150 mounted soldiers, 200 infantrymen, and numerous native recruits, hoping to uncover vast treasures of gold and precious stones. However, the reality of the journey would fall far short of these expectations.

The expedition traveled through what is now the American Southwest, including present-day Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas. Coronado’s men encountered various indigenous groups, including the Zuni and the Hopi, but instead of discovering golden cities, they found small Pueblo communities with humble dwellings. Coronado’s soldiers looted whatever they could—primarily blankets, pottery, and other goods—but the supposed cities of gold were nowhere to be found. Eventually, the expedition turned back after reaching the Great Plains of Kansas, disillusioned and empty-handed.

The Discovery of the Cannon

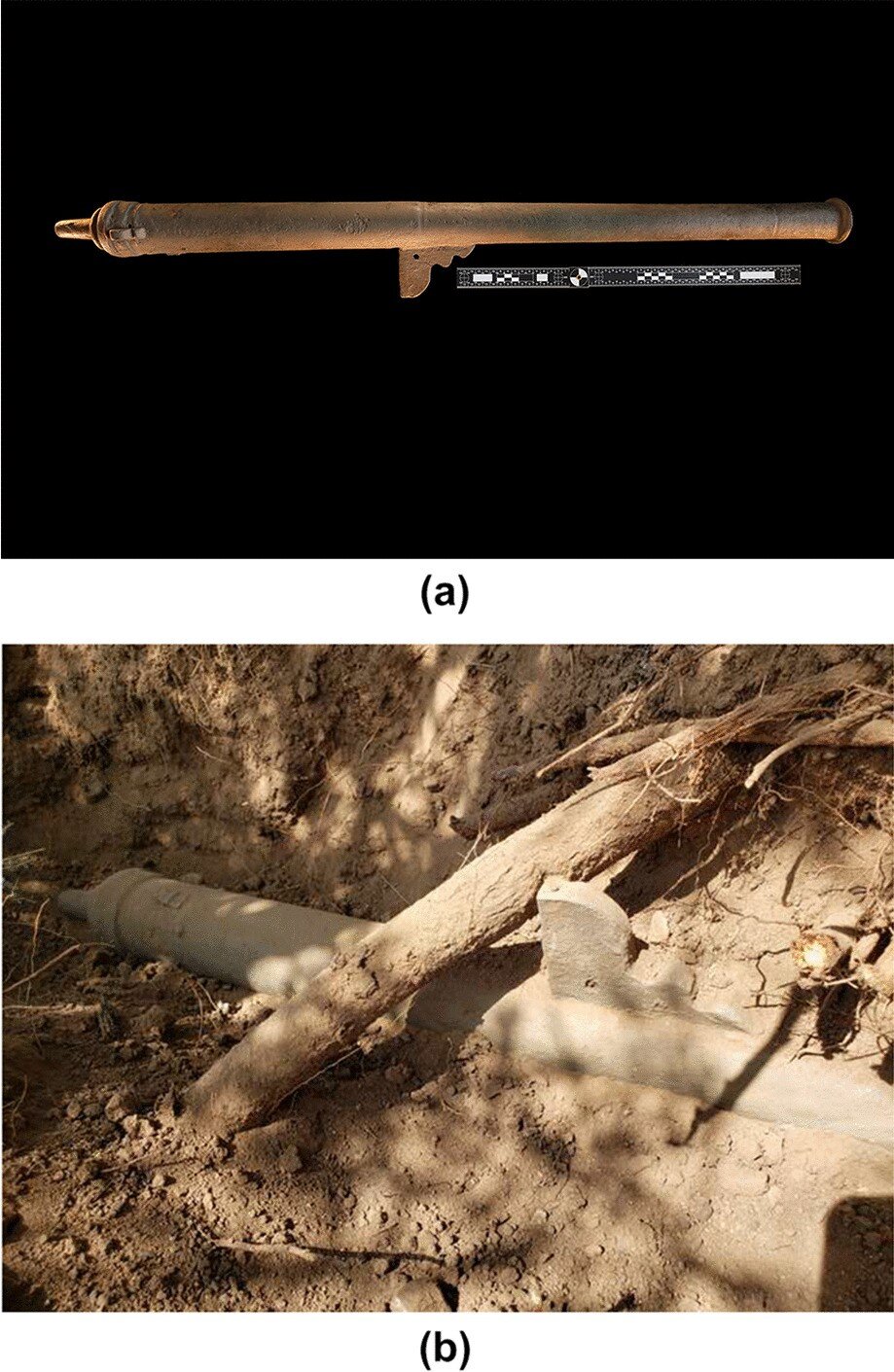

Fast forward to the present day, where an archaeological team working in the Santa Cruz Valley of Arizona has uncovered a remarkable artifact that connects directly to Coronado’s ill-fated expedition. The cannon, made of bronze, was found lying on the floor of a Spanish stone-and-adobe structure. This structure has been dated to the Coronado era using advanced methods such as radiocarbon dating and optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) techniques, which help to pinpoint the time frame in which the cannon was deposited.

The cannon, measuring 42 inches in length and weighing approximately 40 pounds, is a type of firearm known as a “wall gun.” Wall guns were early firearms designed to be operated by two people and were often used for defensive or offensive purposes along fortification walls. In the context of the Coronado expedition, these guns were likely intended to breach the defenses of the indigenous communities they encountered, especially the adobe walls of native dwellings. This suggests that the expedition not only sought to conquer and enslave but also to break down the physical barriers that separated the Spanish from the resources they were after.

The cannon was found unloaded, which raises intriguing questions about its use. It shows no signs of battle damage, leading researchers to wonder why it was abandoned in this seemingly strategic location. Historical accounts of the Coronado expedition indicate that the local Sobaipuri O’odham people launched an attack on the Spanish settlement in the region, forcing the Spaniards to retreat. This connection between the discovery of the cannon and the historical narrative of conflict suggests that the gun may have been left behind during a hasty withdrawal, further deepening the mystery surrounding its abandonment.

The Design and Craftsmanship of the Cannon

The cannon’s design and manufacturing process offer additional insights into its origins. It was sand-cast, with three sprue marks along the bottom axis and four iron pins used in the casting process. The relatively plain and unadorned design of the cannon suggests that it was likely cast in Mexico or the Caribbean, rather than in Spain, where more ornate and decorative casting methods were common. The simplicity of the design may reflect the practical needs of the expedition, where functionality outweighed the aesthetic considerations that would have been more important in a European context.

Another intriguing possibility is that the cannon may have been purchased or acquired from a previous Spanish expedition, potentially even from Juan Ponce de León’s ill-fated ventures into the New World. This raises the prospect that the cannon, though it is an early firearm, may have been part of a broader network of weaponry circulating among Spanish explorers in the Americas at the time.

The Context of Early Spanish-Native American Interactions

The discovery of the cannon, along with other artifacts found at the site, offers valuable clues about the nature of early Spanish-Native American interactions in the Southwest. Alongside the cannon, the excavation team found European pottery, olive jar sherds, glass shards, and weapon parts—all of which align with the historical period of the Coronado expedition. These artifacts provide tangible evidence of the Spanish presence in the region and their attempts to impose their culture and military power on the indigenous populations.

The confrontation between the Spanish and the local Sobaipuri O’odham people, as indicated by the lead shot and distinctive arrowheads found at the site, highlights the tense and often violent nature of these early encounters. The O’odham, like many other native groups, resisted the intrusion of the Spanish, and the conflict between the two sides resulted in the eventual abandonment of the settlement by the conquistadors. The presence of native weapons at the site underscores the role of indigenous resistance in shaping the course of Spanish exploration and settlement in North America.

The Importance of the Cannon Discovery

This cannon is the first known firearm directly associated with the Coronado expedition, and it offers a fascinating window into the weaponry and tactics used by the Spanish during their exploration of the American Southwest. While firearms were not widely used by native groups at the time, the Spanish brought advanced weaponry—such as guns, steel swords, and armor—that gave them a significant military advantage over the indigenous populations they encountered. The presence of such a weapon in the Arizona desert provides important evidence of the Spanish attempts to exert control over the region and expand their empire in the Americas.

Moreover, the discovery of the cannon is a significant moment in the study of early colonial history in the United States. It underscores the complex relationships between European explorers and the native populations they encountered, as well as the role of military technology in shaping the outcomes of these interactions. By offering a physical connection to one of the most ambitious and ultimately unsuccessful expeditions in the history of European exploration, this cannon enhances our understanding of the broader context of early American colonialism.

Ongoing Research and Future Insights

As researchers continue to analyze the cannon and other artifacts recovered from the site, further insights into the origins of the weapon and the broader context of the Coronado expedition are expected. The cannon’s exact place of manufacture, whether in Mexico, the Caribbean, or elsewhere, remains a subject of ongoing investigation. Additionally, the researchers plan to conduct further analyses of other artifacts at the site to better understand the daily life of the Spanish explorers, as well as the nature of their interactions with indigenous peoples.

The discovery of the cannon offers a fascinating glimpse into a pivotal moment in the history of European exploration in the Americas. It is a reminder of the complexity and consequences of early encounters between European colonizers and Native American populations, and it invites further exploration of the role that weaponry, military strategy, and cultural exchange played in shaping the history of the Southwest.

In the end, the cannon unearthed in Arizona is not just a relic of a failed conquest; it is a tangible link to a past that continues to shape the present. The story of Coronado’s expedition, marked by ambition, failure, and conflict, is brought to life in this discovery, offering a new chapter in the ongoing saga of American history.

Reference: Deni J. Seymour et al, Coronado’s Cannon: A 1539-42 Coronado Expedition Cannon Discovered in Arizona, International Journal of Historical Archaeology (2024). DOI: 10.1007/s10761-024-00761-7