In the grand, sprawling history of life on Earth, mass extinctions serve as stark reminders of nature’s power to reset the evolutionary clock. Giant asteroid impacts, intense volcanic activity, and even runaway climate change have all been cast in starring roles as harbingers of doom. But a growing body of evidence is pointing toward another, more cosmic culprit in at least two of these ancient die-offs: nearby supernova explosions.

A recent study from researchers at Keele University, published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, suggests that two of Earth’s greatest biological crises—the Ordovician-Silurian extinction around 445 million years ago and the late Devonian extinction approximately 372 million years ago—may have been set in motion by the lethal effects of massive stars dying in spectacular fashion.

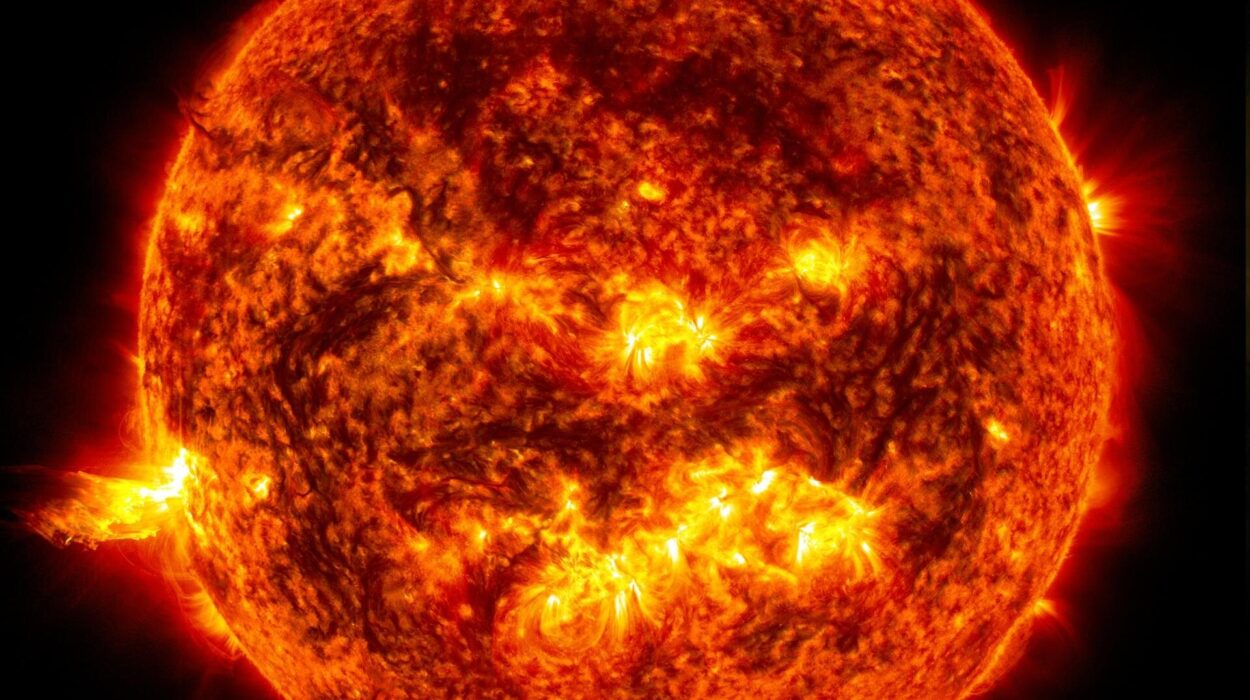

These powerful explosions, known as supernovae, don’t just light up the galaxy with their brilliance; they spew deadly radiation and energetic particles across vast distances. When one erupts nearby, it has the potential to strip away the protective layers of a planet’s atmosphere, leaving life on the surface dangerously exposed. In Earth’s case, scientists believe that these stellar death throes may have shredded the ozone layer, bombarded ecosystems with ultraviolet radiation, and triggered climatic chaos in the form of acid rain and cooling temperatures.

“We often think of space as distant and detached from our lives here on Earth,” explains Dr. Alexis Quintana, the study’s lead author and now a researcher at the University of Alicante. “But supernovae show that the universe is deeply connected to the fate of life on this planet. If a star dies too close to home, the effects can be devastating.”

The Smoking Gun in the Sky

For decades, the causes of Earth’s five major mass extinctions have been hotly debated. Some are linked to well-documented events—like the Chicxulub asteroid that wiped out the dinosaurs 66 million years ago—but others remain shrouded in mystery. Among them are the Ordovician-Silurian and late Devonian extinctions, which together annihilated a staggering 60% to 70% of all species on Earth, most of them marine life. At the time, life was still mostly confined to oceans, and these die-offs radically reshaped early evolutionary paths.

Previous studies have speculated about climate shifts and ocean anoxia (oxygen depletion) as potential causes. But they have struggled to identify what might have triggered such extreme changes on a global scale. The new research takes a different approach—looking outward, rather than inward, for answers.

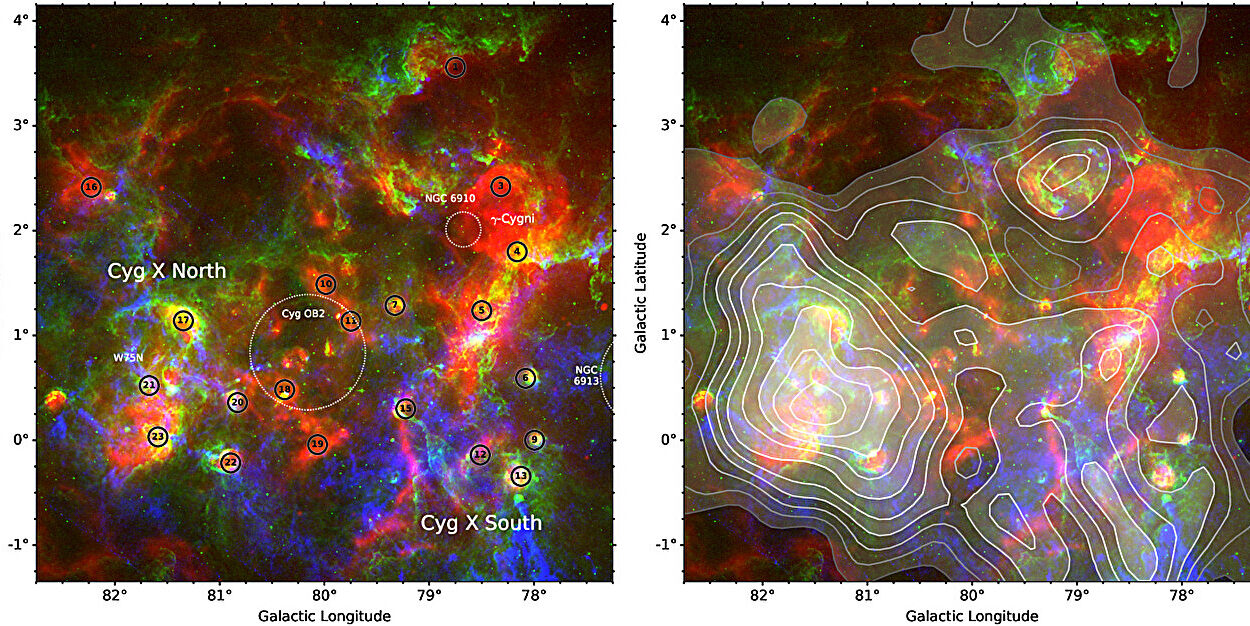

By analyzing the distribution and life cycles of massive stars—specifically, OB stars—in our galactic neighborhood, the team from Keele University calculated how often supernovae have likely occurred within dangerously close range to Earth over geological time. OB stars are short-lived, brilliant behemoths that often end their lives in supernova explosions, releasing torrents of high-energy radiation.

Their census, which examined stars within a kiloparsec (about 3,260 light-years) of the Sun, allowed the researchers to estimate how frequently supernovae have occurred close enough to Earth to potentially impact its biosphere. They found that the supernova rate near Earth aligns closely with the timings of these two ancient mass extinction events.

“Supernovae are the universe’s double-edged sword,” says Dr. Nick Wright of Keele University, a co-author of the study. “On one hand, they create and disperse the heavy elements—like carbon, oxygen, and iron—that are essential for life. But on the other, they have the power to destroy life if you happen to be in the wrong place at the wrong time.”

What Happens When a Star Dies Nearby?

The death of a massive star in a supernova is an astounding spectacle. In an instant, the collapsing core rebounds, and an immense shockwave tears through the outer layers of the star. The explosion can outshine an entire galaxy for weeks. But for nearby planets, it’s no light show. It’s a cataclysm.

When a supernova detonates within about 30 light-years of Earth (or 10 parsecs), its radiation can strip away the ozone layer, which shields life from the Sun’s harmful ultraviolet (UV) rays. Without this protective blanket, UV radiation floods the surface, increasing mutation rates, damaging DNA, and killing off vulnerable organisms—especially those in the upper layers of the oceans where life was thriving hundreds of millions of years ago.

But the damage doesn’t stop there. The cascade of cosmic rays—high-energy particles—can linger for thousands of years, interacting with Earth’s atmosphere in ways that could spark acid rain or even alter global climates. The result? A one-two punch of environmental upheaval and mass extinction.

There’s compelling indirect evidence that such events may have played out in Earth’s distant past. Studies of ancient rocks have found odd isotopic signatures, such as iron-60, a radioactive isotope produced in supernovae and deposited on Earth’s crust. While these deposits date to more recent events, they hint that supernova explosions have rained their radioactive debris onto Earth before—and could have been responsible for catastrophic changes in the deep past.

Linking the Stars to Life’s Collapse

The Ordovician-Silurian extinction event, around 445 million years ago, obliterated about 60% of marine invertebrate species. Ice ages and falling sea levels have long been blamed, but something had to trigger these changes. Similarly, the late Devonian extinction, roughly 372 million years ago, wiped out nearly 70% of species, including many jawless fish and reef-builders, with long-lasting repercussions for marine ecosystems.

The Keele University team’s work suggests that nearby supernovae could have set off a domino effect: first damaging the ozone layer, then allowing UV radiation to decimate life, and finally sending the planet into climate turmoil.

“We’re not saying supernovae are the sole cause of these extinctions,” Dr. Quintana clarifies. “But the timing and potential effects fit the pattern remarkably well.”

Their models indicate that Earth has likely experienced several supernovae within 20 parsecs (about 65 light-years) over the last 500 million years—close enough to do serious damage. The coincidence between these rates and the timing of major die-offs supports the idea that we may owe some of life’s greatest catastrophes not to impacts from above—but to distant explosions of dying stars.

Are We in the Crosshairs Today?

Should we be worried about nearby stars poised to go supernova? Not in the immediate future.

In our galactic neighborhood, the two most likely candidates for supernova explosions are Betelgeuse and Antares—both red supergiants nearing the end of their lives. However, they are at least 500 light-years away. That’s far beyond the danger zone for Earth. Even if Betelgeuse were to explode tomorrow (and there’s been speculation it could), its impact on us would likely be limited to a dazzling light show, visible even in daylight, rather than an extinction-level event.

Astronomers estimate that in galaxies like the Milky Way, one or two supernovae occur each century. But the probability of one going off close enough to Earth to cause major harm is exceedingly low in our era. Still, cosmic threats are real, and as we develop new technologies—like gravitational wave detectors—we’re gaining tools to understand and perhaps anticipate these distant dangers.

Life’s Fragile Connection to the Cosmos

The new findings add another layer to the story of how life on Earth is inextricably linked to the broader universe. The same cosmic engines that forge the building blocks of life also have the power to extinguish it. Supernovae are both creators and destroyers, seeding galaxies with elements that make planets—and life—possible, while occasionally snuffing out entire branches of evolution with their deadly energy.

Dr. Wright puts it eloquently: “Massive stars shape the cosmos in ways we are only beginning to understand. They create the conditions for life—and sometimes, they take it away.”

The research opens fascinating new windows into the interplay between cosmic events and life on Earth, offering a stark reminder that while our planet may seem isolated, it is part of a dynamic, sometimes dangerous universe.

Final Thoughts

For now, Earth seems safe from nearby stellar explosions. But the evidence that past mass extinctions were triggered by supernovae invites us to reflect on the fragile balance that makes life possible. The next time you look up at the stars, remember: the brilliance you see is not just light, but also a story of creation and destruction—one that may have shaped the very life we live today.

Reference: Alexis L. Quintana et al, A census of OB stars within 1 kpc and the star formation and core collapse supernova rates of the Milky Way, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Societyacademic.oup.com/mnras/article … 0.1093/mnras/staf083 . On arXiv (2025). DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2503.08286