Imagine standing in the middle of a vast, silent plain, staring up at a sky so ancient it predates the stars themselves. You are listening, not with ears, but with instruments tuned to the faintest whispers of time. What you hear is the oldest sound in the universe—the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB). It’s the afterglow of the Big Bang, a relic of the universe’s fiery birth, still humming softly, eternally, across the cosmic expanse.

The CMB is the fossil light of creation itself. It’s the echo of a moment so distant in time that, when it first radiated, there were no galaxies, no stars, no planets—only the primordial soup of existence just beginning to cool. In those first few hundred thousand years, the universe was a chaotic, seething plasma. Yet in that chaos, there was the blueprint for everything we know.

This is the story of the Cosmic Microwave Background: a journey back to the beginning, a message sent across 13.8 billion years of cosmic time, and a key to understanding who we are, where we came from, and what our universe is made of.

The First Light: A Universe Awakens

Let’s rewind the clock. Not a million years, not a billion—but all the way back to 13.8 billion years ago, to the moment we call the Big Bang. In the beginning, there was no space, no time, no matter as we understand it. Everything—energy, matter, space, time—was compressed into an incomprehensibly hot and dense point.

And then, in a blinding instant, it began to expand. This expansion was not like an explosion, but rather space itself stretching and unfolding. The newborn universe was a plasma, a superheated soup of photons, electrons, protons, and neutrons. Photons—the particles of light—were constantly colliding with charged particles. In this inferno, light couldn’t travel freely; it was trapped in a fog of particles, endlessly bouncing, unable to escape.

But the universe was expanding. And as it expanded, it cooled. For hundreds of thousands of years, this process continued, until one pivotal moment arrived.

Around 380,000 years after the Big Bang, the temperature of the universe cooled enough for protons and electrons to combine, forming neutral hydrogen atoms. This event is called recombination. With no free electrons left to scatter them, photons were finally released. The universe became transparent. This first light, free at last, began to travel through space—radiating outward in all directions.

That ancient light is still traveling today. And we can see it, not with our eyes, but with radio telescopes and sensitive instruments. We call it the Cosmic Microwave Background. It is the oldest light in the universe, a snapshot of the cosmos as it was in its infancy. It’s not just light—it’s a time capsule from the dawn of time.

The Discovery That Changed Everything

For most of human history, the night sky was thought of as eternal and unchanging. Stars burned without beginning or end, the cosmos an endless and static expanse. But the 20th century turned that notion on its head.

In 1929, Edwin Hubble discovered that the universe was expanding. Galaxies were moving away from each other, and the farther they were, the faster they fled. This led to the revolutionary idea of the Big Bang—that the universe had a beginning.

If the universe had a hot, dense beginning, then scientists reasoned that there should be leftover radiation from that primordial fireball. In 1948, George Gamow, along with his colleagues Ralph Alpher and Robert Herman, predicted that this radiation would still exist, though cooled by the expansion of the universe. It would be faint, but it would be everywhere. They calculated that it should now appear as microwave radiation.

For years, this remained a theoretical prediction—until a serendipitous discovery changed everything.

In 1964, two radio astronomers, Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson, were working at Bell Labs in New Jersey. They were testing a sensitive antenna, designed for satellite communications, when they encountered an annoying, persistent hiss. No matter where they pointed their antenna, the noise remained. They cleaned out bird droppings from the equipment, ruled out nearby cities as the source, but the noise refused to go away.

Unbeknownst to them, just 60 miles away at Princeton University, a team of physicists led by Robert Dicke was preparing to search for the very same thing—a faint microwave signal predicted by Big Bang theory. When Penzias and Wilson heard of Dicke’s work, they realized what they had found. The hiss in their antenna was the Cosmic Microwave Background, the afterglow of the Big Bang itself.

For their discovery, Penzias and Wilson were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1978. But more than awards, their finding cemented the Big Bang theory as the leading explanation for the origin of the universe. The universe wasn’t eternal and unchanging—it had a beginning, and it left behind a whisper of its birth.

Mapping the Echo: The Universe as a Baby

For decades after Penzias and Wilson’s discovery, the CMB was studied in greater and greater detail. But the true breakthrough came in 1989, when NASA launched the Cosmic Background Explorer (COBE) satellite. COBE’s mission was to map the faint variations in the CMB’s temperature—the tiny fluctuations that told the story of how the early universe evolved.

COBE confirmed what theorists had suspected: the CMB wasn’t perfectly uniform. There were tiny ripples, differences in temperature on the order of one part in 100,000. These minuscule differences were the seeds of everything we see today—galaxies, stars, planets, life. The slightly denser areas of the early universe had just a bit more gravity, causing them to pull in more matter over time. These were the beginnings of structure in the cosmos.

The data from COBE was called “the discovery of the century, if not of all time” by Stephen Hawking. But COBE was just the beginning.

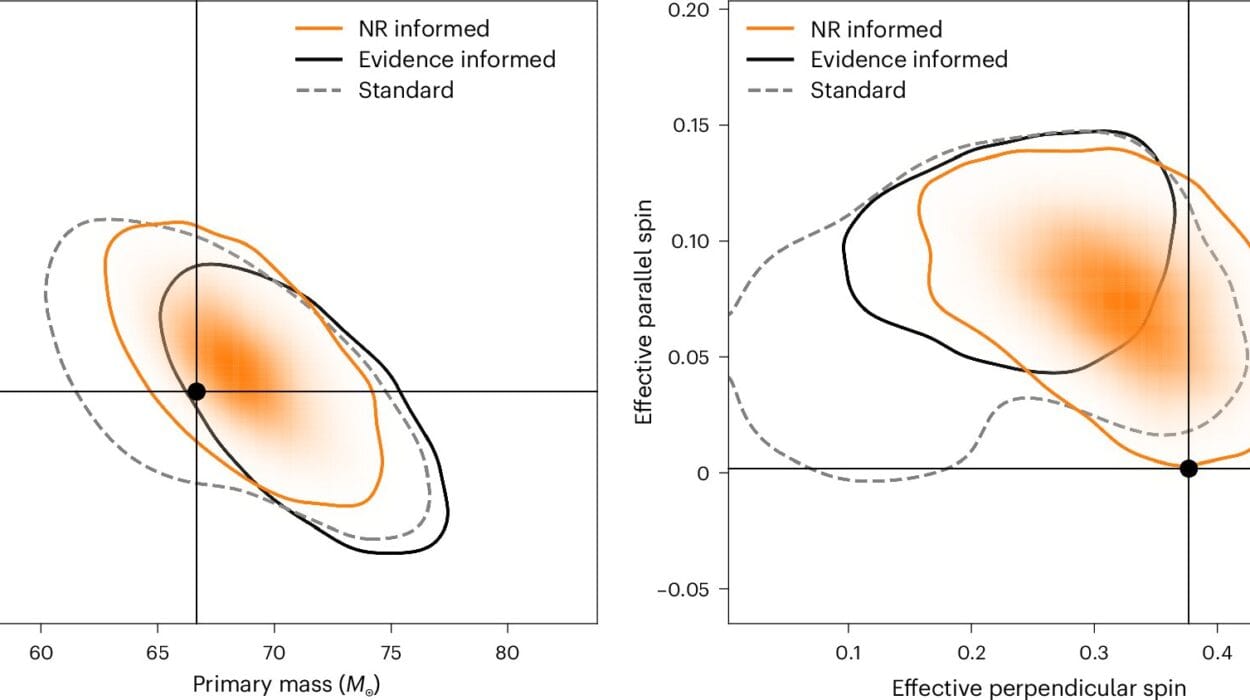

In 2001, NASA launched the Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP), which provided an even clearer, more detailed map of the CMB. WMAP’s data refined our understanding of the universe’s age (13.8 billion years), its composition (about 5% ordinary matter, 27% dark matter, and 68% dark energy), and its geometry (flat).

Then, in 2009, the Planck Space Telescope—operated by the European Space Agency—took our view of the CMB to a new level. Planck’s measurements were so precise they revealed subtle asymmetries and anomalies that are still being debated by cosmologists today.

Each new map of the CMB is like opening a photo album from the universe’s childhood. And each photo reveals new secrets about its growth, its nature, and its ultimate fate.

What the CMB Tells Us About Everything

The Cosmic Microwave Background isn’t just a pretty picture of the young universe. It’s a cosmic Rosetta Stone, containing the key to unlocking fundamental mysteries about everything.

The Universe’s Age and Composition

By studying the CMB’s temperature fluctuations and their distribution, scientists have been able to pin down the universe’s age with remarkable precision: 13.8 billion years. And the CMB tells us what the universe is made of: ordinary matter, dark matter, and dark energy.

The Shape of Space

The CMB also helps answer a mind-bending question: What is the shape of the universe? By analyzing the patterns in the CMB, scientists have determined that space is flat, not curved like a sphere or saddle-shaped. This flatness supports the theory of cosmic inflation, a brief but stupendous expansion that occurred fractions of a second after the Big Bang.

Inflation and the Seeds of Structure

The CMB provides evidence for inflation, the theory that the universe expanded exponentially faster than the speed of light in the tiniest sliver of its first second. Inflation explains why the universe appears so uniform on large scales and why tiny quantum fluctuations were stretched into the seeds of galaxies.

Clues to the Mysterious Dark

While the CMB doesn’t show dark matter or dark energy directly, it reveals their fingerprints. Dark matter’s gravitational pull shaped the distribution of hot and cold spots in the CMB. Dark energy’s influence is detected in the accelerating expansion of the universe, inferred from how those fluctuations line up.

Hints of New Physics

Some anomalies in the CMB puzzle scientists to this day. There’s the “Axis of Evil”, a strange alignment of temperature fluctuations that shouldn’t exist in a random universe. There are cold spots that seem too large to be explained by standard models. Are these signs of new physics? Evidence of a multiverse? Or just statistical flukes? We don’t yet know.

Listening to the Echoes: How We See the CMB

The CMB isn’t something you can see with the naked eye. It’s microwave radiation, which lies beyond visible light on the electromagnetic spectrum. But if your eyes were sensitive to microwaves, the entire sky would glow with a nearly uniform light, slightly brighter or dimmer in tiny spots.

Radio telescopes and space-based instruments are our eyes for this ancient light. Ground-based observatories, like the South Pole Telescope and Atacama Cosmology Telescope, peer into the CMB from Earth’s most remote, high-altitude locations, where the atmosphere is thin and dry.

But the most detailed measurements come from satellites like COBE, WMAP, and Planck, which orbit beyond our planet, free from Earthly interference.

In fact, a tiny fraction of the static you see on an old TV tuned to no channel comes from the CMB. When you see that snow on the screen, a part of it is the ancient afterglow of the Big Bang, washing over you from all directions.

The Sound of Creation

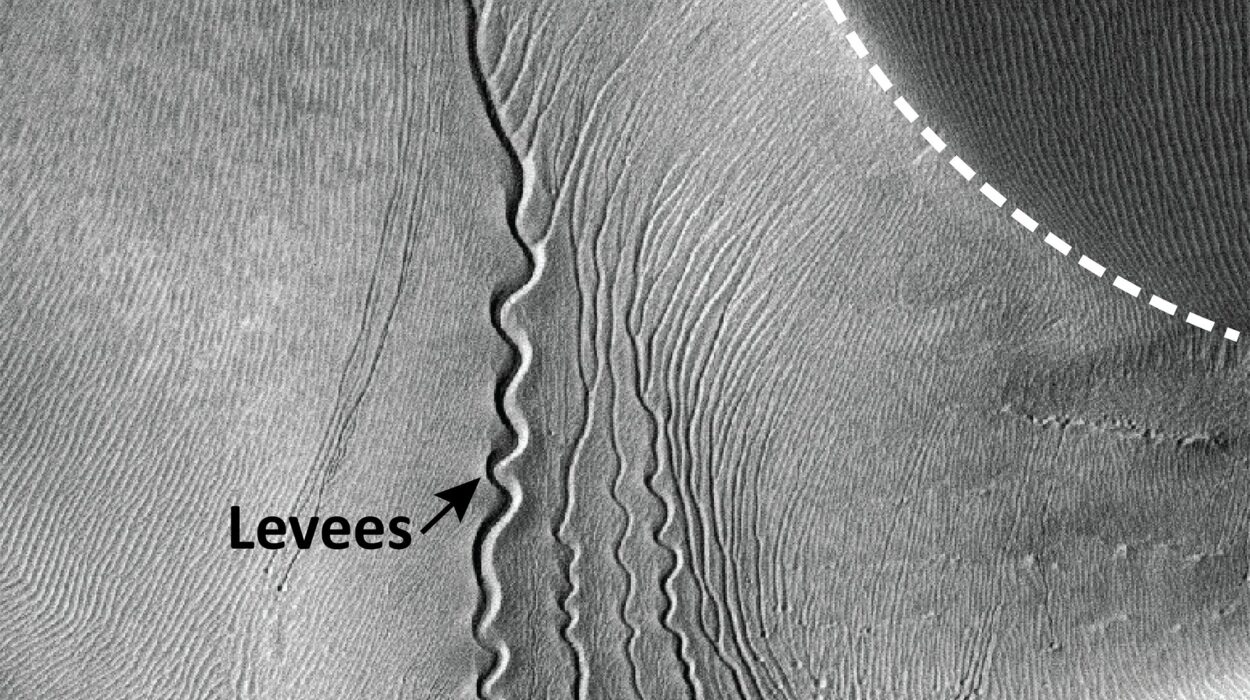

The CMB isn’t just light—it can also be thought of as sound. In the early universe, waves of compressed and rarefied plasma rippled through space, like sound waves through air. These acoustic oscillations are frozen into the CMB’s patterns.

Scientists have converted these primordial sound waves into audio that we can hear. The result is a deep, low hum, a kind of cosmic music that echoes across billions of years. It’s not the sound of stars or galaxies, but the universe itself, resonating as it was born.

The Legacy of the Echo

The Cosmic Microwave Background is more than just a scientific curiosity. It’s the ultimate connection to our origins. Every photon in the CMB has traveled for nearly 14 billion years to reach us. When you look at the map of the CMB, you are looking at the universe as it was before there were stars, before there were galaxies, before there was anything we recognize.

The CMB tells a story of simplicity that gave rise to complexity. From tiny fluctuations in temperature—ripples in a sea of plasma—came galaxies, stars, planets, and eventually life. You. Me. Everything.

It is an echo of creation that will never fade.

The Future of Cosmic Listening

What’s next for our understanding of the CMB? Scientists are planning new missions, like the LiteBIRD and CMB-S4 projects, which will search for evidence of primordial gravitational waves—ripples in spacetime predicted by inflation theory. These gravitational waves, if detected, would be imprinted on the CMB in a distinctive pattern of polarization called B-modes.

Finding these B-modes would be like hearing the faint whisper of the universe’s birth pangs, confirming some of our wildest ideas about how everything began.

Echoes That Endure

The Cosmic Microwave Background is the most ancient light we can observe. But it’s more than just a snapshot of the past. It’s a living testament to the grand story of existence.

In those faint microwaves, we find evidence of our universe’s fiery birth, its childhood struggles, and its journey to the vast cosmos we see today. We find ourselves woven into that story—because we are made from the stars that formed in those early galaxies, which arose from those first tiny ripples.

The CMB is not just an echo of creation. It is the voice of the cosmos itself, still speaking after 13.8 billion years. And as we listen more closely, we may yet hear new truths whispered from the dawn of time.