Two years into its mission, the European Space Agency’s Euclid space telescope is living up to its promise of unlocking the secrets of the cosmos. Launched on July 1, 2023, Euclid is no ordinary observatory. Hovering a million miles from Earth at the second Lagrange point (L2), it’s meticulously scanning the universe to construct the largest, most detailed 3D map of galaxies, stars, and cosmic structures we’ve ever attempted. But Euclid isn’t just delivering pretty pictures—it’s giving astronomers the data to rewrite the story of how our universe formed, evolved, and continues to expand.

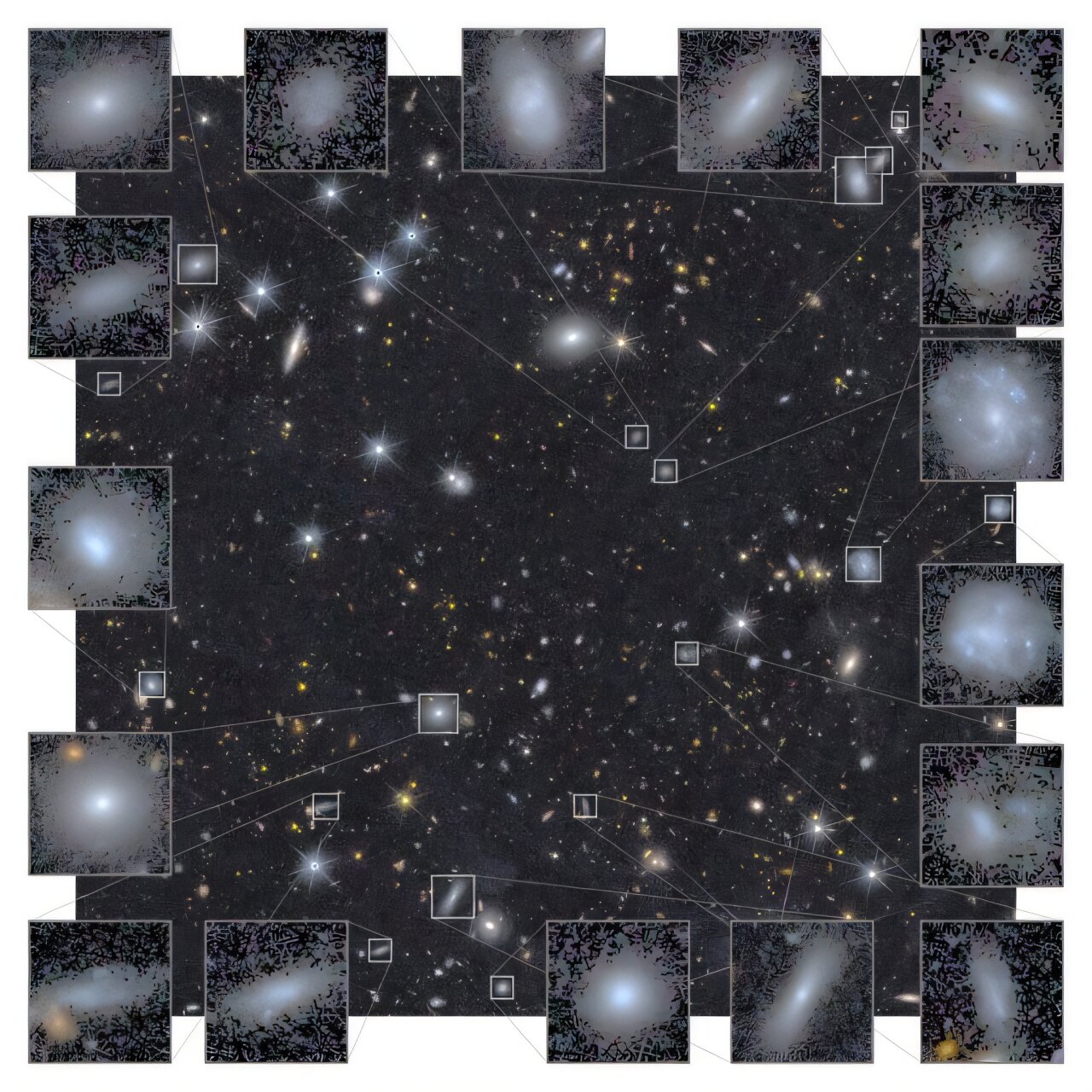

Now, thanks to Euclid’s unprecedented imaging capabilities, a team of astronomers at the University of Innsbruck has made an extraordinary discovery: 2,674 dwarf galaxies lurking in just 25 images from the telescope’s treasure trove of data. These faint, often overlooked galactic minnows hold the keys to some of cosmology’s biggest questions.

Euclid’s Mission: Charting the Dark Universe

The Euclid space telescope was designed for an ambitious goal: to peel back the cosmic veil and illuminate the dark side of the universe. About 95% of the universe is made of dark energy and dark matter—enigmatic substances that scientists can’t see directly but whose fingerprints are etched across the cosmos. Dark energy is driving the accelerated expansion of the universe, while dark matter holds galaxies together with its invisible gravitational pull.

By creating a vast 3D map of billions of galaxies spread across 10 billion light-years, Euclid helps scientists understand how these mysterious components shape the universe on the largest scales. How do galaxies cluster together? How fast has the universe expanded over time? Where does gravity reign supreme, and where does dark energy push back? Euclid is on a quest to find out.

Innsbruck’s Cosmic Census: A Trove of Dwarf Galaxies

Back on Earth, the Euclid consortium—a global network of over 2,000 scientists from around 300 institutions—is digging deep into Euclid’s data streams. Among them is the University of Innsbruck’s Department of Astro- and Particle Physics, where Francine Marleau and her colleagues, including Marlon Fügenschuh and Selin Sprenger, have been hunting for galaxies that are often overshadowed by their more glamorous, larger counterparts.

These dwarf galaxies are the most common type in the universe, yet they remain among the least understood. Smaller and less luminous than their massive cousins, they play an outsized role in our cosmic history. They are believed to be the building blocks of larger galaxies, offering clues to how galactic giants like our Milky Way came to be. And because dwarf galaxies are heavily influenced by their environments, they are excellent testbeds for studying dark matter and cosmological models.

Using sophisticated semi-automated methods, Marleau’s team combed through 25 images from Euclid’s powerful instruments. What they found exceeded all expectations: 2,674 dwarf galaxies scattered across the cosmic landscape. Each one was meticulously cataloged and classified according to its morphology (shape), distance, stellar mass, and galactic environment.

The breakdown? About 58% of the dwarfs are elliptical galaxies—smooth, rounded galaxies with little structure. Another 42% are irregular galaxies, their chaotic shapes hinting at a tumultuous past. A small but intriguing minority includes galaxies rich in globular clusters (1%), ones with prominent galactic nuclei (4%), and around 6.9% exhibiting blue compact centers—regions of intense, recent star formation.

A New Window into Galactic Evolution

What makes this discovery so remarkable isn’t just the number of dwarf galaxies detected, but the insight they offer into galaxy formation across different epochs and environments.

“We took advantage of the unprecedented depth, spatial resolution, and field of view of the Euclid data,” says Marleau. “This work highlights Euclid’s remarkable ability to detect and characterize dwarf galaxies, enabling a comprehensive view of galaxy formation and evolution across diverse mass scales, distances, and environments.”

Unlike previous surveys that focused on nearby galaxies, Euclid’s deep gaze stretches across vast cosmic distances. This allows astronomers to track how dwarf galaxies evolved over billions of years. Were they always small and faint, or did some shrink through violent galactic encounters? How did they survive the gravitational pull of larger galaxies? And crucially, how does their distribution test current theories of how dark matter is supposed to behave?

For cosmologists, dwarf galaxies are like litmus tests. Many models of the universe predict a specific abundance and distribution of these galaxies. If observations match those predictions, it’s a thumbs-up for our understanding of dark matter and galaxy formation. If not, scientists might need to go back to the drawing board.

The Power Behind the Images

So, what makes Euclid such a game-changer in this field? It comes down to a combination of cutting-edge technology and mission design.

At the heart of Euclid is a 1.2-meter diameter telescope equipped with two sophisticated instruments: the VISible instrument (VIS) and the Near Infrared Spectrometer and Photometer (NISP). Together, they capture high-resolution images and spectra of galaxies in both visible and near-infrared light. This dual capability enables Euclid to see faint, distant galaxies with incredible clarity, even those whose light has traveled billions of years to reach us.

Its field of view is enormous by space telescope standards—covering about the area of two full moons in the sky at once. Over the course of its six-year primary mission, Euclid is expected to observe roughly 36% of the sky. That’s more than 15,000 square degrees of deep-space data, packed with billions of galaxies at different stages of evolution.

But Euclid’s true power lies in its ability to combine sharp images with precise distance measurements. By observing the way light from distant galaxies is distorted by the gravitational pull of intervening dark matter—a phenomenon called weak gravitational lensing—Euclid provides a three-dimensional map of both visible and invisible structures in the universe.

A Universe in Motion: Tracing the Cosmic Web

One of Euclid’s biggest scientific contributions will be its ability to chart the cosmic web—the vast network of filaments and voids that make up the large-scale structure of the universe. Galaxies aren’t scattered randomly through space; they’re woven into this cosmic web, their positions influenced by dark matter and the gravitational forces shaping the cosmos.

By studying how dwarf galaxies trace these filaments and populate cosmic voids, astronomers hope to better understand the role of dark matter in assembling these structures. Are there more dwarf galaxies in denser regions of the cosmic web, or do they prefer the emptiness of cosmic voids? How does their distribution evolve over time? The answers could help resolve long-standing puzzles in cosmology, such as the “missing satellites problem,” which describes the discrepancy between the number of dwarf galaxies predicted by dark matter models and those we actually observe.

Beyond the Stars: Probing Dark Energy’s Mysterious Hand

While dwarf galaxies offer a window into dark matter, Euclid’s mission also targets dark energy—the enigmatic force accelerating the universe’s expansion. By measuring the distribution of galaxies over cosmic time, Euclid allows scientists to reconstruct how the universe expanded after the Big Bang.

This data is vital for testing theories about dark energy. Is it a constant force, as Einstein’s cosmological constant suggests? Or is it dynamic, changing its properties over time? Euclid’s galaxy maps will help determine whether current theories hold up or if something more exotic—like modifications to the laws of gravity themselves—is at play.

Global Collaboration: Science Without Borders

The Euclid project exemplifies international collaboration on a grand scale. Over 2,000 scientists, engineers, and technicians from 300 institutions across 13 European countries, the United States, Canada, and Japan are working together to make sense of the torrent of data pouring in from space. Ground-based observatories supplement Euclid’s data with observations in other wavelengths, providing a fuller picture of the galaxies under scrutiny.

Francine Marleau and her team’s work on dwarf galaxies is just one piece of this enormous scientific puzzle. Across the globe, teams are analyzing everything from galaxy shapes to gravitational lensing patterns to cosmic voids.

What’s Next for Euclid?

Euclid’s mission is just getting started. Over the coming years, the telescope will continue surveying the skies, delivering data that will keep scientists busy for decades to come. Each new dataset opens up fresh opportunities for discovery—from previously unseen galaxies to potential cracks in our cosmological models.

For Marleau’s team and the international Euclid consortium, the work is exhilarating and humbling. “We’re looking billions of years into the past,” Marleau reflects. “Each galaxy we study is a time capsule, showing us how the universe grew from its earliest days to what we see now.”

And as Euclid sharpens its view of the cosmos, it promises to reshape our understanding of the universe’s past, present, and future.

Reference: F. R. Marleau et al, Euclid: Quick Data Release (Q1) — A census of dwarf galaxies across a range of distances and environments, arXiv (2025). DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2503.15335