Humanity has always been curious about the vastness beyond our skies. Since the dawn of civilization, we’ve gazed into the night, tracing constellations and wondering if we are truly alone in the universe. As our understanding of the cosmos deepened, so did our questions. Are there other worlds out there? Could they harbor life? And most tantalizing of all—could we ever find another Earth?

Welcome to the thrilling, high-stakes hunt for Earth 2.0. It’s a story that stretches across light-years, driven by cutting-edge science and an age-old longing to find our place among the stars.

The Exoplanet Revolution

For most of human history, our knowledge of planets was limited to the eight (sorry, Pluto) orbiting our sun. The idea of planets circling other stars was a matter of speculation, science fiction, and philosophical musings. Ancient thinkers like Giordano Bruno dared to dream of “innumerable suns” each surrounded by “innumerable earths.” But without evidence, these musings remained just that—dreams.

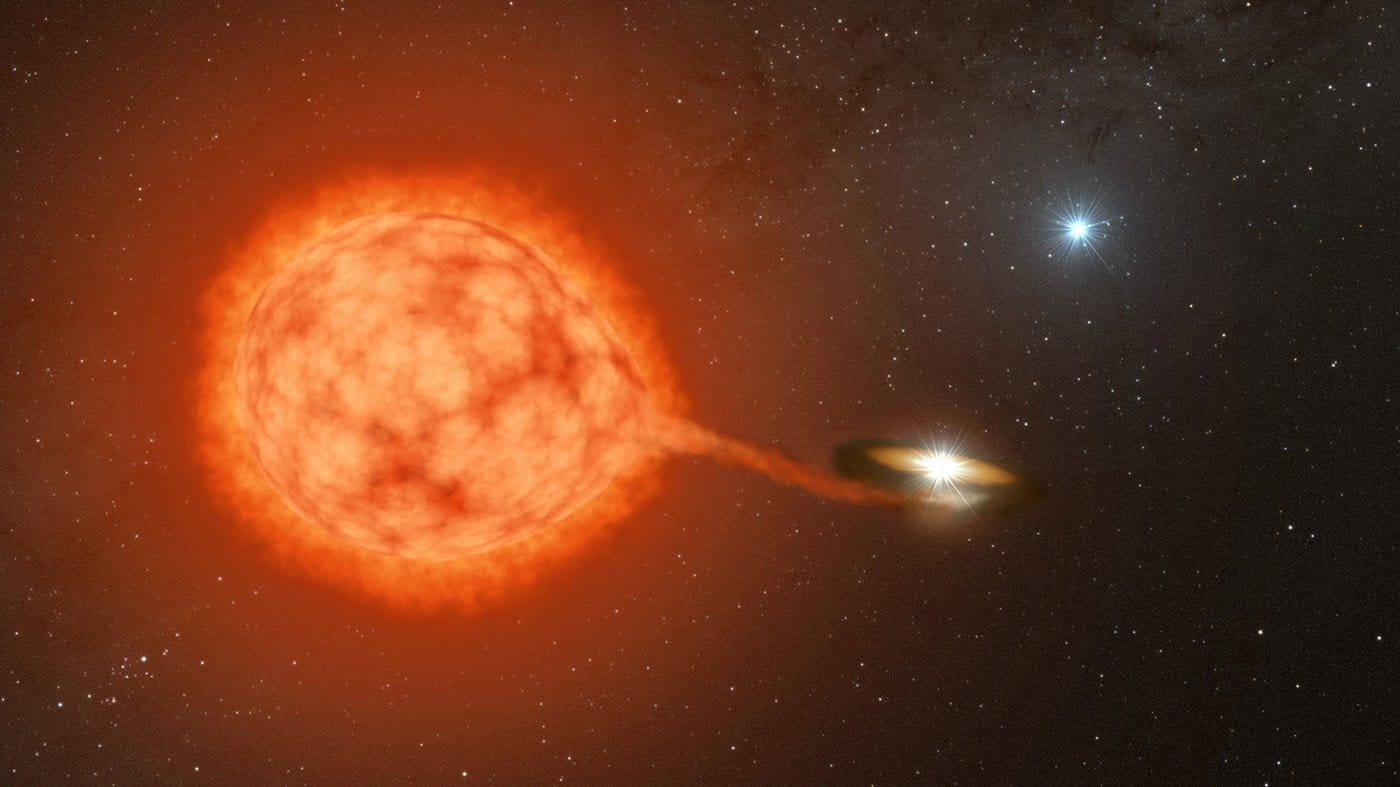

Everything changed in 1992, when astronomers Aleksander Wolszczan and Dale Frail announced the discovery of two planets orbiting a pulsar, PSR B1257+12, a rapidly spinning corpse of a star. These worlds weren’t anything like Earth; they were scorched and bathed in deadly radiation. But the discovery was groundbreaking. For the first time, we knew planets existed beyond our solar system.

Then in 1995, Swiss astronomers Michel Mayor and Didier Queloz stunned the world with the discovery of 51 Pegasi b, the first exoplanet found orbiting a sun-like star. It was a gas giant, larger than Jupiter, and whipped around its star in just four days—clearly nothing like Earth. Yet it ignited a scientific revolution. If there was one planet, there might be billions more.

And there are.

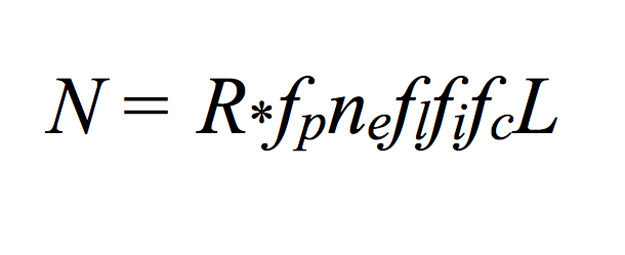

How Many Worlds Are Out There?

Today, we know of over 5,500 confirmed exoplanets and thousands more candidates waiting to be verified. These worlds come in all shapes and sizes: scorching hot Jupiters that hug their stars, icy Neptunes adrift in the cold, and rocky Super-Earths that spark our imagination.

The numbers are staggering. The Milky Way alone contains over 100 billion stars, and most of those stars have planets. NASA’s Kepler Space Telescope revealed that there could be billions of Earth-sized planets orbiting in the habitable zones—the sweet spots where liquid water could exist.

Suddenly, Earth doesn’t seem so unique after all.

What Exactly Are We Looking For?

When we talk about “Earth 2.0,” we don’t mean an exact copy of our blue world, down to the continents and cloud patterns. We’re looking for a planet that ticks certain boxes:

- Size and Composition: Ideally, it should be a rocky planet—not a gas giant—similar in size to Earth. Too small, and it might lose its atmosphere. Too large, and it could turn into a mini-Neptune with crushing gravity.

- Distance from Its Star: It needs to orbit within the habitable zone, where temperatures are just right for liquid water. Too close, and it’s a scorched wasteland. Too far, and it’s a frozen desert.

- Atmosphere: A protective atmosphere can regulate temperature, shield the planet from harmful radiation, and maybe even support life.

- Stability: A stable star, not prone to deadly flares or massive radiation bursts, increases the chances of life.

In short, we’re looking for the Goldilocks planet—not too hot, not too cold, but just right.

How Do We Find These Distant Worlds?

You’d think spotting planets light-years away would be impossible. They’re small, dim, and often lost in the blinding glare of their stars. Yet scientists have developed ingenious methods to find them.

1. The Transit Method

This is the workhorse of planet hunting. If a planet crosses in front of its star as seen from Earth, it causes a tiny dip in the star’s brightness. Sensitive telescopes, like Kepler and TESS, watch for these blips. Repeated dips at regular intervals mean a planet is likely there.

This method tells us the planet’s size, its orbital period, and gives clues about its atmosphere. It’s like watching a mosquito pass in front of a car’s headlight from miles away—but it works.

2. The Radial Velocity Method (Doppler Wobble)

A planet’s gravity tugs on its star, causing the star to wobble ever so slightly. This wobble affects the star’s light, shifting its spectrum toward red or blue as it moves. Sensitive instruments can detect these shifts, telling us the planet’s mass and orbital characteristics.

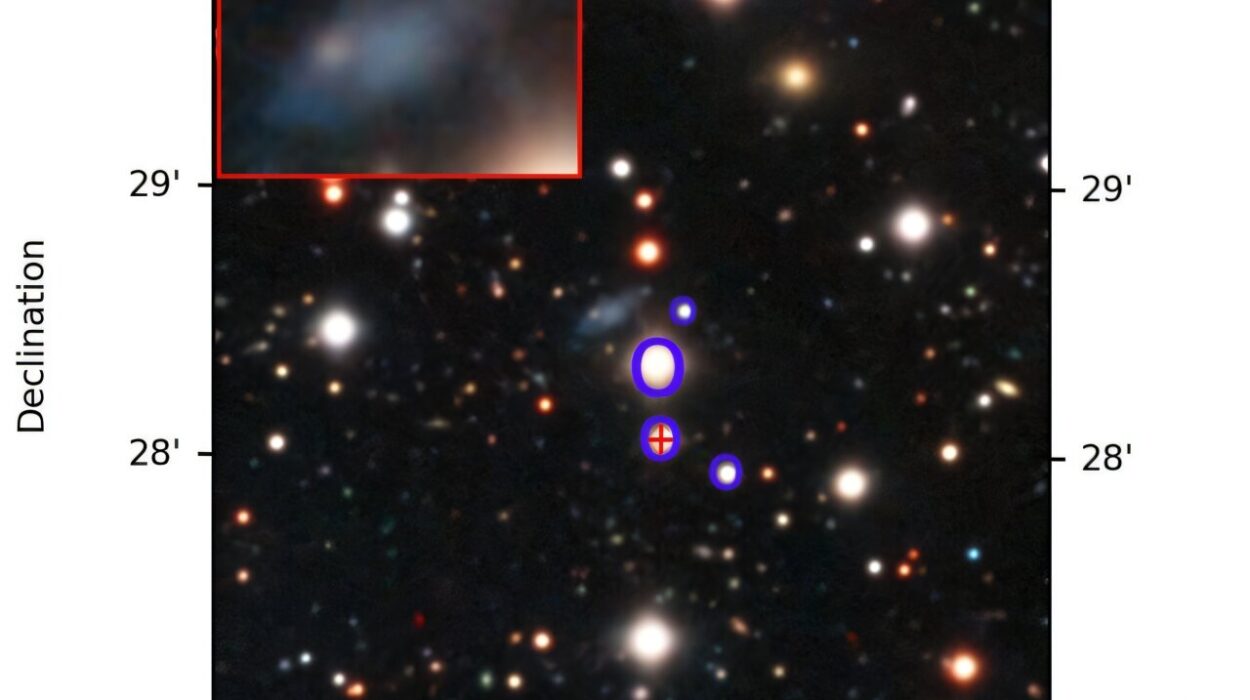

3. Direct Imaging

This is incredibly hard but not impossible. By blocking out a star’s light with a coronagraph or starshade, astronomers can sometimes take actual pictures of distant planets. It’s like spotting a firefly next to a lighthouse from across the ocean.

4. Gravitational Microlensing

When a star passes in front of another star, its gravity can bend and magnify the light. If the lensing star has a planet, it causes an extra blip in the light. This method can spot planets thousands of light-years away, even in distant parts of the galaxy.

Kepler’s Legacy and the Era of TESS

Launched in 2009, NASA’s Kepler Space Telescope changed everything. Over its nine-year mission, Kepler stared at 150,000 stars and found more than 2,600 confirmed exoplanets, many in the habitable zone.

Kepler taught us that planets are everywhere. Its data suggested that one in five sun-like stars has an Earth-sized planet in the habitable zone. That’s potentially billions of Earth-like worlds in our galaxy alone.

Now, Kepler’s successor, the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), is scanning the entire sky. TESS focuses on nearby, bright stars, making its discoveries perfect targets for follow-up with more powerful telescopes.

The James Webb Space Telescope: Game Changer

Enter the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). Launched in December 2021, JWST is humanity’s most powerful space observatory. One of its key missions is to study exoplanet atmospheres in unprecedented detail.

By analyzing the starlight that filters through a planet’s atmosphere during a transit, JWST can detect gases like water vapor, methane, carbon dioxide, and even oxygen—potential signs of life. Imagine knowing the chemical makeup of a planet’s air from light-years away.

JWST has already peered into the atmospheres of distant exoplanets, and it’s just getting started.

Meet Some Earth 2.0 Candidates

1. Kepler-186f

About 500 light-years away, Kepler-186f is one of the first Earth-sized planets found in its star’s habitable zone. It’s slightly larger than Earth and orbits a red dwarf star. While red dwarfs can be volatile, this planet is a tantalizing prospect.

2. Proxima Centauri b

Orbiting the closest star to our solar system, just 4.24 light-years away, Proxima Centauri b is at least 1.3 times Earth’s mass. It lies in its star’s habitable zone, but its red dwarf host is prone to flares. Still, its proximity makes it a prime candidate for study—and possibly one day, visitation.

3. TRAPPIST-1 System

This system, 40 light-years away, boasts seven Earth-sized planets, with at least three in the habitable zone. It’s a cosmic jackpot. These worlds orbit a cool red dwarf, and while conditions are still uncertain, the sheer number of potentially habitable planets is extraordinary.

4. LHS 1140 b

Another super-Earth about 40 light-years away, LHS 1140 b orbits in the habitable zone of its star. It’s denser than Earth, suggesting a rocky world with potential for water.

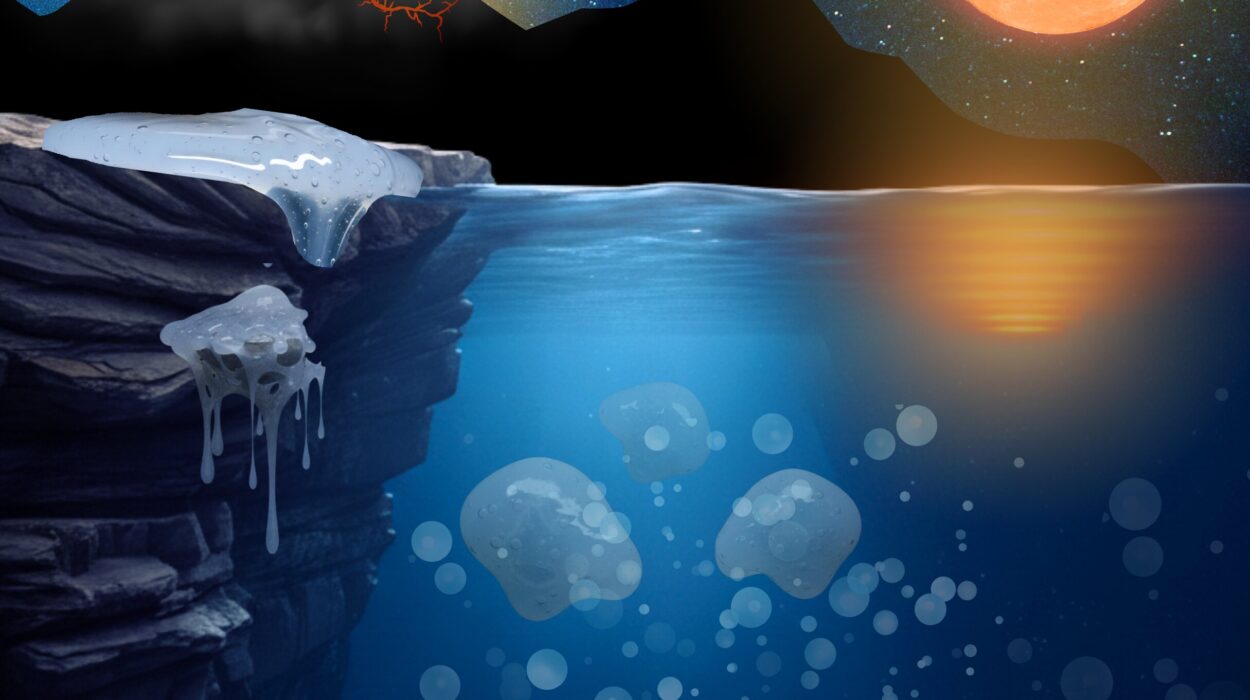

Could Life Exist Out There?

Finding an Earth-like planet is one thing. Proving it’s alive is another.

We search for biosignatures—chemical signs that life might be present. On Earth, plants produce oxygen, and life processes release methane. The simultaneous presence of these gases, along with water vapor, could be a smoking gun.

But we must be careful. Some processes can mimic biosignatures. Volcanoes can release methane. Ultraviolet light can break apart water to produce oxygen. That’s why context is key.

The ultimate prize? A world where multiple biosignatures suggest a thriving ecosystem, perhaps even something more exotic than anything we can imagine.

Why Finding Earth 2.0 Matters

Some might wonder: why do we spend billions searching for distant worlds?

The answers are as old as humanity itself. Curiosity. The desire to understand our place in the cosmos. The hope of finding life beyond Earth. And perhaps, the survival of our species.

Carl Sagan called Earth the “pale blue dot.” But we are vulnerable here. Climate change, asteroid impacts, or other catastrophes could end life as we know it. Finding another home—even if it takes centuries—might be the key to humanity’s future.

And let’s not forget the wonder. The idea that somewhere out there, another Earth circles its sun. Oceans sparkle beneath alien skies. Maybe life swims in its seas or gazes back at us, wondering if they’re alone.

The Future of Exoplanet Exploration

The quest for Earth 2.0 is just beginning. Future missions promise even more exciting discoveries:

- PLATO (ESA): Launching in 2026, PLATO will focus on Earth-like planets around sun-like stars, hunting for worlds that are truly like our own.

- LUVOIR and HabEx (NASA concepts): Massive space telescopes that could directly image Earth-like planets and study their atmospheres in detail.

- Breakthrough Starshot: A bold plan to send tiny, laser-driven spacecraft to Proxima Centauri within a generation. Imagine getting close-up images of another world.

Conclusion: The Cosmic Frontier Awaits

The search for Earth 2.0 isn’t just about science. It’s about the human spirit. We are explorers at heart, compelled to cross oceans, scale mountains, and now—reach for the stars.

Somewhere out there, a second Earth may be waiting. Oceans glimmering under unfamiliar suns. Mountains rising beneath strange skies. Life, in forms we can only dream of, may already be calling it home.

And one day, we might stand on its surface, look up at its skies, and remember our first home, a pale blue dot lost in the vast darkness—but never forgotten.

The hunt for Earth 2.0 is the greatest adventure of our time. And we’re just getting started.