When it comes to understanding the societies of ancient Europe, archaeologists have traditionally relied on fragments of pottery, remnants of house foundations, and the occasional human remains to piece together the complex puzzle of past civilizations. But what if these material traces could tell us more than just the basic functions of daily life? What if they could offer insights into the deeper societal dynamics, the philosophies, and even the sense of identity that shaped these ancient communities?

A groundbreaking study, led by two archaeologists and a philosopher from the ROOTS Cluster of Excellence at Kiel University, presents a new way of examining the social organization and identity of Europe’s earliest mega-settlements. By applying the United Nations’ Human Development Index (HDI)—a modern tool for measuring human well-being and social progress—the team has developed an innovative approach to bridge the gap between the distant past and the present, revealing fascinating new perspectives on ancient societies.

The Power of the “Capability Approach”

The method proposed by the researchers is rooted in the “capability approach,” a philosophical framework first introduced by the Indian economist and philosopher Amartya Sen during the 1970s and 1980s. Sen’s concept focuses on human well-being not as a simple measure of material wealth but as a broader spectrum that includes the opportunities and abilities of individuals and communities to live fulfilling lives. In other words, human well-being is shaped not just by possessions but by the freedom and capacity to achieve one’s potential.

In contemporary settings, this capability approach has become the theoretical foundation for the United Nations’ Human Development Index (HDI), which is used to assess the quality of life across countries by considering factors like education, life expectancy, and income. However, when it comes to studying ancient societies, applying these modern concepts to material remains can be a daunting challenge. After all, how do you measure the dynamic elements of human well-being in a society that left behind only static physical remnants?

This is precisely the puzzle that the researchers sought to solve, and they believe they have developed a promising solution. By adapting the HDI framework to archaeological data, they have opened up new possibilities for understanding how early European mega-settlements were organized and how their inhabitants lived and interacted.

The Challenge: From Static Artifacts to Dynamic Social Life

One of the main hurdles in applying the capability approach to archaeology is the difficulty in connecting material culture—the pots, tools, and remnants of buildings—with the intangible elements of human life, such as social interactions, political structures, and personal well-being. According to Dr. René Ohlrau, one of the co-authors of the study, the challenge lies in how to “reconstruct dimensions of the dynamic activity behind it” using only the static evidence left behind.

Material culture, like a broken piece of pottery or the outline of a dwelling foundation, gives us a glimpse into the lives of the people who created them. However, understanding the nuances of social organization, cultural values, and the quality of life requires a more nuanced approach. Traditional archaeological methods have often focused on technological innovations, shifts in population size, and environmental factors as key explanations for the success or decline of ancient communities. But these explanations, while useful, may not fully capture the underlying social forces that drove change.

This is where the Human Development Index comes in. The HDI provides a way to measure not just the material wealth of a society, but also the broader dimensions of human life that influence well-being, such as health, education, and access to opportunities. By using this framework, the researchers are able to offer new explanations for the success of Europe’s first mega-settlements.

A New Lens on the Cucuteni-Trypillia Communities

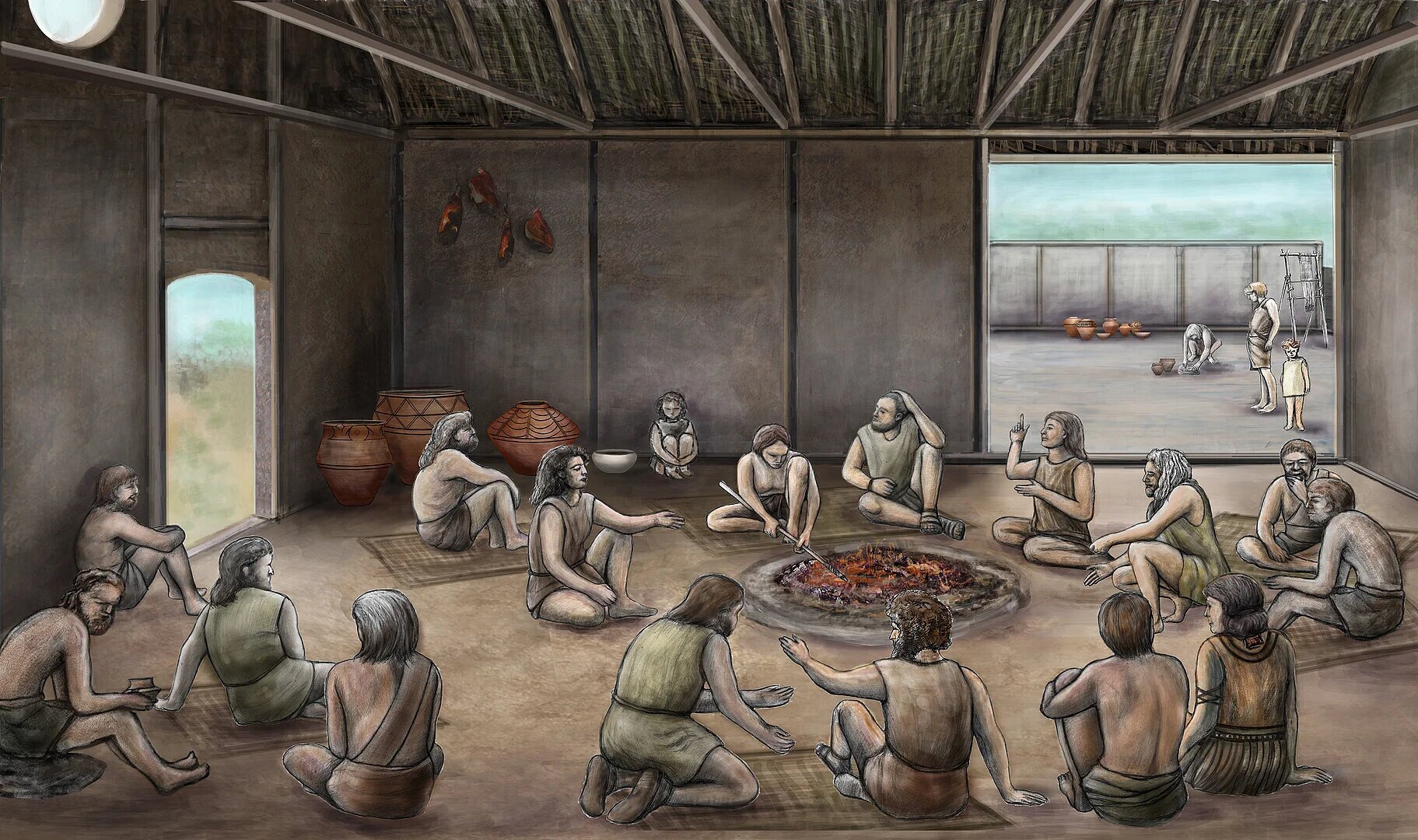

To test their new approach, the researchers focused on the Cucuteni-Trypillia culture, a group of prehistoric communities that thrived in what is now Romania, Moldova, and Ukraine between around 5050 BCE and 2950 BCE. Known for their large, circular settlements that spanned up to 320 hectares and housed thousands of people, the Cucuteni-Trypillia societies were among the first in Europe to create “mega-settlements.”

The settlements were remarkably advanced for their time, with evidence of complex social organization, specialized craft production, and early forms of agriculture. The size and sophistication of these settlements suggest a level of social cohesion and cooperation that was likely unprecedented in Europe at the time. However, traditional explanations have often focused on external factors, such as population growth or climate change, as the driving forces behind the rise of these settlements.

What makes this study unique is its ability to shift the focus from external pressures to internal factors—specifically, the well-being and opportunities available to individuals within the society. By applying the Human Development Index framework, the researchers found that the Cucuteni-Trypillia settlements were characterized by a high degree of social equality, particularly in their peak phase. The settlements offered extensive opportunities for people to engage in various activities, from agricultural work to artistic production, and this sense of personal agency and fulfillment may have been one of the key factors that contributed to their success.

Social Equality and the Expansion of Opportunities

The concept of “opportunity” is central to the researchers’ new interpretation of the Cucuteni-Trypillia settlements. Traditional theories have often suggested that innovations in technology and political organization were reactions to population pressures or environmental challenges. However, the researchers propose a different explanation: it could have been the expansion of opportunities for individuals within the society that attracted more people and led to population growth, which in turn spurred technological and social innovation.

According to Dr. Vesa Arponen, one of the lead authors, this perspective challenges the conventional wisdom in archaeology. Instead of viewing innovations as reactions to crises, the new approach suggests that innovations may have emerged as part of a process of expanding human capabilities. The opportunity for individuals to lead active, fulfilling lives—whether through participating in economic activities, engaging in cultural practices, or contributing to community decision-making—could have created a social environment that encouraged growth and innovation.

For example, the introduction of new agricultural tools or the development of more efficient building techniques may have been driven not only by external pressures but also by the desire of individuals to improve their quality of life and the opportunities available to them. These advancements, in turn, would have made the settlement more attractive to outsiders, further contributing to its growth.

This reinterpretation of the Cucuteni-Trypillia societies also suggests that social equality played a significant role in their success. The high level of equality in these communities, as revealed by archaeological evidence, likely allowed for greater social mobility and a more equitable distribution of resources, which would have contributed to a more stable and resilient society.

Implications for Future Research

The new approach developed by the researchers has broad implications for the field of archaeology. By applying the capability approach and the Human Development Index to the study of ancient societies, they are opening up new avenues for understanding how human well-being was shaped in the past. This framework offers a way to move beyond traditional models that focus solely on material wealth or technological innovation and instead consider the broader dimensions of human life that contribute to a society’s success.

In the future, this approach could be applied to other archaeological contexts, shedding light on the social dynamics and opportunities that shaped ancient communities across Europe and beyond. By expanding the scope of analysis to include factors like social equality, personal agency, and access to opportunities, archaeologists can gain a deeper understanding of the factors that contributed to the rise of complex societies.

As Dr. Arponen notes, this approach challenges traditional patterns of explanation in archaeology and opens the door to new discussions about the meaning and significance of archaeological finds. It provides a fresh perspective on the past and encourages archaeologists to think beyond the material artifacts and consider the broader social and philosophical contexts in which these objects were created.

Conclusion

The application of the Human Development Index to archaeological data represents a significant shift in how we approach the study of ancient societies. By focusing not just on material wealth but on the broader opportunities available to individuals and communities, this innovative framework offers new insights into the social dynamics of Europe’s first mega-settlements. As researchers continue to explore this approach in future studies, we may gain a richer, more nuanced understanding of the societies that laid the foundations for modern civilization.

Reference: V. P. J. Arponen et al, The Capability Approach and Archaeological Interpretation of Transformations: On the Role of Philosophy for Archaeology, Open Archaeology (2024). DOI: 10.1515/opar-2024-0013