Imagine a universe drenched in darkness. No stars twinkling in distant skies, no galaxies swirling in elegant spirals, no light at all. This was the cosmos shortly after the Big Bang—a vast, expanding sea of blackness. For hundreds of millions of years, there were no stars, no galaxies, no planets. But then something extraordinary happened.

Tiny seeds of matter began collapsing under their own gravity, giving birth to the first stars. And from these stars came the first galaxies—massive islands of light in an otherwise dark universe. These pioneering galaxies blazed across the void, breaking the cosmic darkness and filling the universe with First Light.

This is the story of the first galaxies—how they formed, how they changed everything, and how modern telescopes are uncovering their ancient secrets. It’s a journey across 13 billion years of cosmic history, back to when the very first structures in the universe switched on their lights and transformed the darkness into brilliance.

The Cosmic Dark Ages

Before we can talk about the first galaxies, we have to understand what came before them. The early universe was an extraordinary place, but also incredibly simple.

The Big Bang, which occurred about 13.8 billion years ago, was the event that created space and time itself. In its immediate aftermath, the universe was unimaginably hot and dense—a blinding soup of energy and particles. But as it expanded, it cooled. Within a few hundred thousand years, it settled into a much calmer state.

By 380,000 years after the Big Bang, the universe had cooled enough for protons and electrons to combine and form neutral hydrogen atoms. This process, called recombination, allowed the universe to become transparent to light. That ancient light still exists today as the Cosmic Microwave Background Radiation, the oldest light we can see.

But after recombination, there were no stars or galaxies yet. The universe entered a time known as the Cosmic Dark Ages, lasting for hundreds of millions of years. The only matter was cold, neutral hydrogen gas. No stars shone, no galaxies swirled. The universe was dark, cold, and silent.

Gravity Gets to Work: The First Structures Form

Even during this darkness, things were happening. The universe wasn’t perfectly uniform. Tiny fluctuations in density—imperfections left over from the Big Bang—meant that some regions had slightly more matter than others. Over time, gravity pulled these regions together, drawing gas into clumps.

As these clumps grew larger, their gravitational pull intensified, attracting even more matter. These regions became the first dark matter halos, invisible cocoons of mass that would act as the scaffolding for the first galaxies.

Dark matter—an invisible substance that makes up about 85% of the matter in the universe—played a crucial role. Without it, gravity wouldn’t have been strong enough to gather normal matter into galaxies so early. The first galaxies were born inside these dark matter halos, which provided the gravitational glue to hold them together.

The First Stars Ignite: Population III Stars

Inside these early dark matter halos, clouds of hydrogen gas collapsed further. As they did, the gas compressed and heated up. Eventually, temperatures and pressures at the core of these clouds became high enough to ignite nuclear fusion. The first stars were born.

These stars were very different from the stars we see today. Known as Population III stars, they were the first generation of stars ever to exist. Because they formed from primordial hydrogen and helium (with almost no heavier elements), they behaved differently.

Population III stars were likely massive—many were hundreds of times the mass of our Sun. They burned extremely hot and bright but lived short, violent lives. Within a few million years, they exploded in spectacular supernovae, scattering the first heavy elements—like carbon, oxygen, and iron—into the universe.

These explosions enriched the surrounding gas with metals, which would later help form smaller, more stable stars. But the first stars did something even more important: they began the Epoch of Reionization.

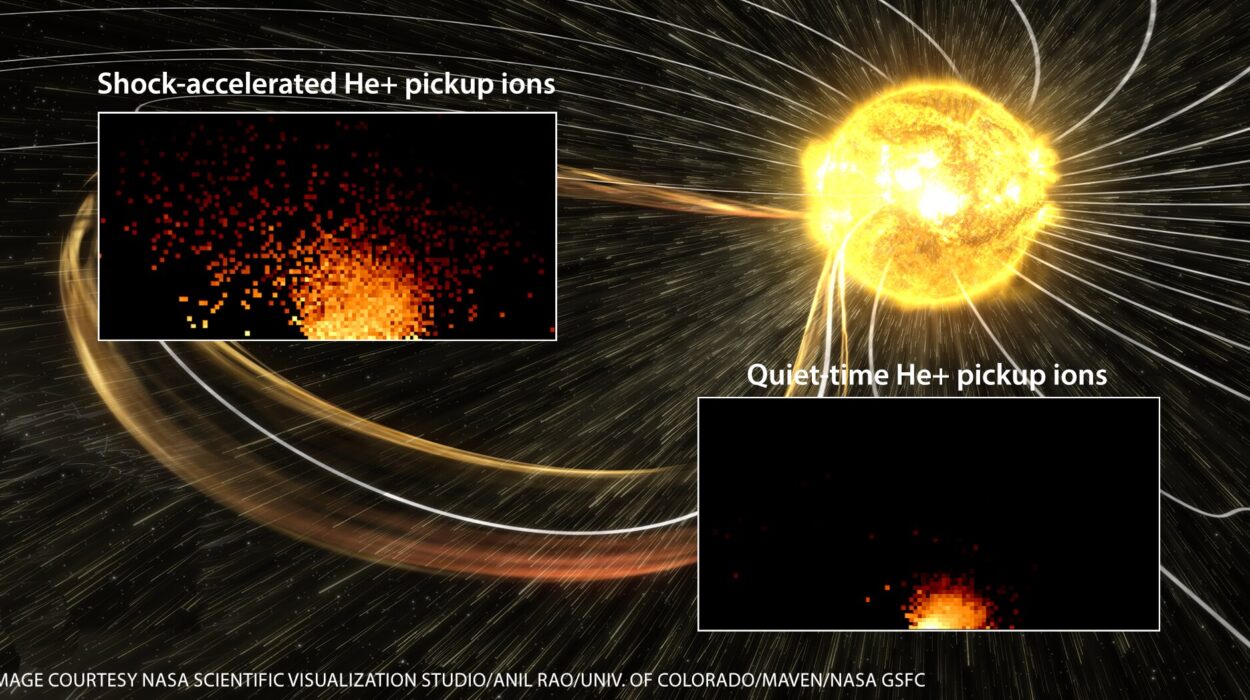

Reionization: Turning the Lights Back On

When the first stars and galaxies switched on, their intense ultraviolet light began to ionize the neutral hydrogen gas that filled the universe. This process—called reionization—transformed the cosmic environment from opaque to transparent, allowing light to travel freely across space.

Reionization marked the end of the Cosmic Dark Ages and the beginning of a universe filled with light and structure. It was a slow process, taking hundreds of millions of years to complete. Galaxies and quasars (powerful objects powered by supermassive black holes) played a key role in driving reionization by emitting enough energetic photons to ionize the intergalactic medium.

By about one billion years after the Big Bang, reionization was mostly complete. The universe had become a vast, clear cosmic ocean where galaxies and stars could shine freely.

The First Galaxies: Building Blocks of the Modern Universe

The first galaxies were different from the grand spiral and elliptical galaxies we see today. They were smaller, less massive, and often irregular in shape. These were the protogalaxies, the seeds from which modern galaxies grew.

Many of the earliest galaxies were only a few thousand light-years across (compared to the Milky Way’s 100,000 light-years). They contained massive stars that lived fast and died young, constantly reshaping their environments with powerful winds and supernova explosions.

These early galaxies merged frequently. Gravity pulled them together into larger and larger systems, growing into the massive galaxies we observe in the nearby universe. Over billions of years, these mergers led to the formation of spiral galaxies, like the Milky Way, and giant elliptical galaxies found in galaxy clusters.

The Role of Black Holes

Even in the earliest galaxies, black holes were present. Some early stars collapsed into black holes when they died, and over time these black holes grew by consuming gas and stars.

In the centers of some early galaxies, supermassive black holes formed. These behemoths powered quasars, which shone as some of the brightest objects in the universe. The light from these quasars helped complete the reionization of the universe and provides astronomers with a way to study the distant cosmos.

But the presence of supermassive black holes so early in cosmic history remains a mystery. How did these objects grow so large so quickly? This question is still one of the great puzzles in modern astrophysics.

How Do We See the Earliest Galaxies?

Studying the first galaxies is incredibly challenging. They are unimaginably distant, and their light has traveled for more than 13 billion years to reach us. This ancient light has been stretched by the expansion of the universe—a phenomenon known as redshift. The higher the redshift, the farther away (and older) the galaxy.

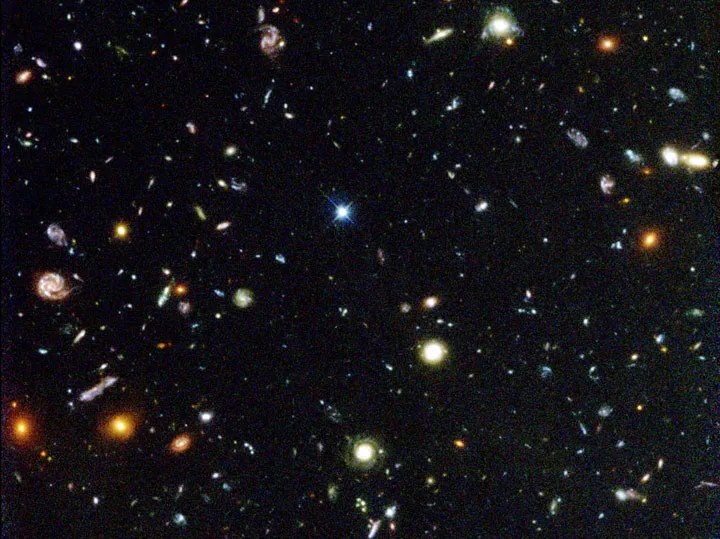

Astronomers rely on powerful telescopes to detect this faint, ancient light. For decades, the Hubble Space Telescope provided incredible views of distant galaxies. Its deep field images revealed thousands of galaxies in tiny patches of sky, including some from the early universe.

But to truly peer into the cosmic dawn, astronomers needed something even more powerful: the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST).

James Webb Space Telescope: Unveiling the First Galaxies

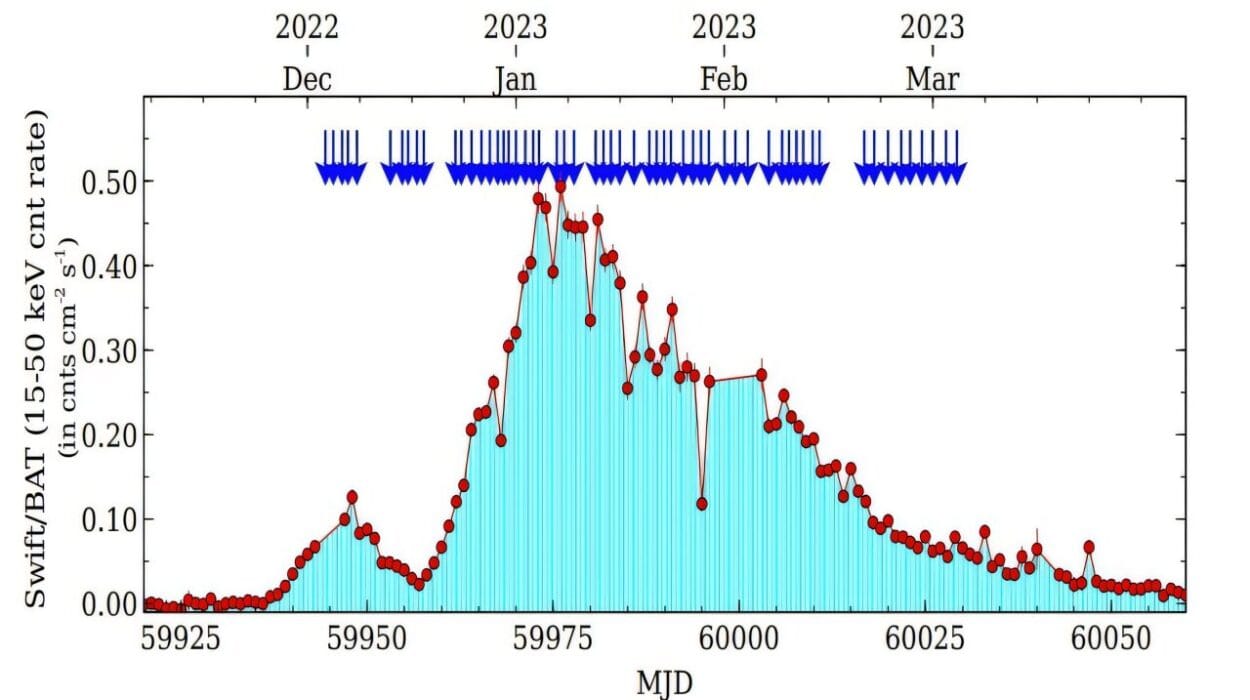

Launched in December 2021, JWST is the most powerful space telescope ever built. Designed to observe in the infrared part of the spectrum, it can detect light from the most distant galaxies—light that has been stretched into infrared wavelengths by redshift.

JWST has already revolutionized our understanding of the early universe. Within months of its first observations, it discovered galaxies that formed just 200-300 million years after the Big Bang—far earlier than expected.

These early galaxies are surprisingly bright and massive, challenging existing models of galaxy formation. How did galaxies grow so big, so fast? The data from JWST suggests that the early universe was much more dynamic and complex than we thought.

JWST has also observed the light from some of the first stars and identified Population III star candidates, giving us our first glimpses into the lives of the universe’s earliest stellar populations.

Galactic Archaeology: What the First Galaxies Tell Us

Studying the first galaxies isn’t just about looking back in time. It’s about understanding how we got here.

The early galaxies forged the first heavy elements, making life as we know it possible. They seeded the cosmos with the building blocks of planets and living organisms. The processes that unfolded in these ancient galaxies paved the way for the formation of stars like our Sun and planets like Earth.

By studying the first galaxies, astronomers are conducting galactic archaeology, uncovering the ancient history of the cosmos. These observations help us understand how galaxies evolve, how stars are born and die, and how the universe transitioned from simplicity to complexity.

The Mysteries That Remain

Even with the power of JWST, many questions remain about the first galaxies:

- How did supermassive black holes form so quickly?

- What were the properties of Population III stars, and how did they influence their galaxies?

- How common were these early galaxies, and how did they cluster together to form large-scale cosmic structures?

- What role did dark matter play in shaping the early universe?

Future telescopes, such as the Extremely Large Telescope (ELT) and the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, will help answer these questions. They will provide sharper images, deeper observations, and more precise measurements of the earliest galaxies and their environments.

Conclusion: First Light and the Dawn of Everything

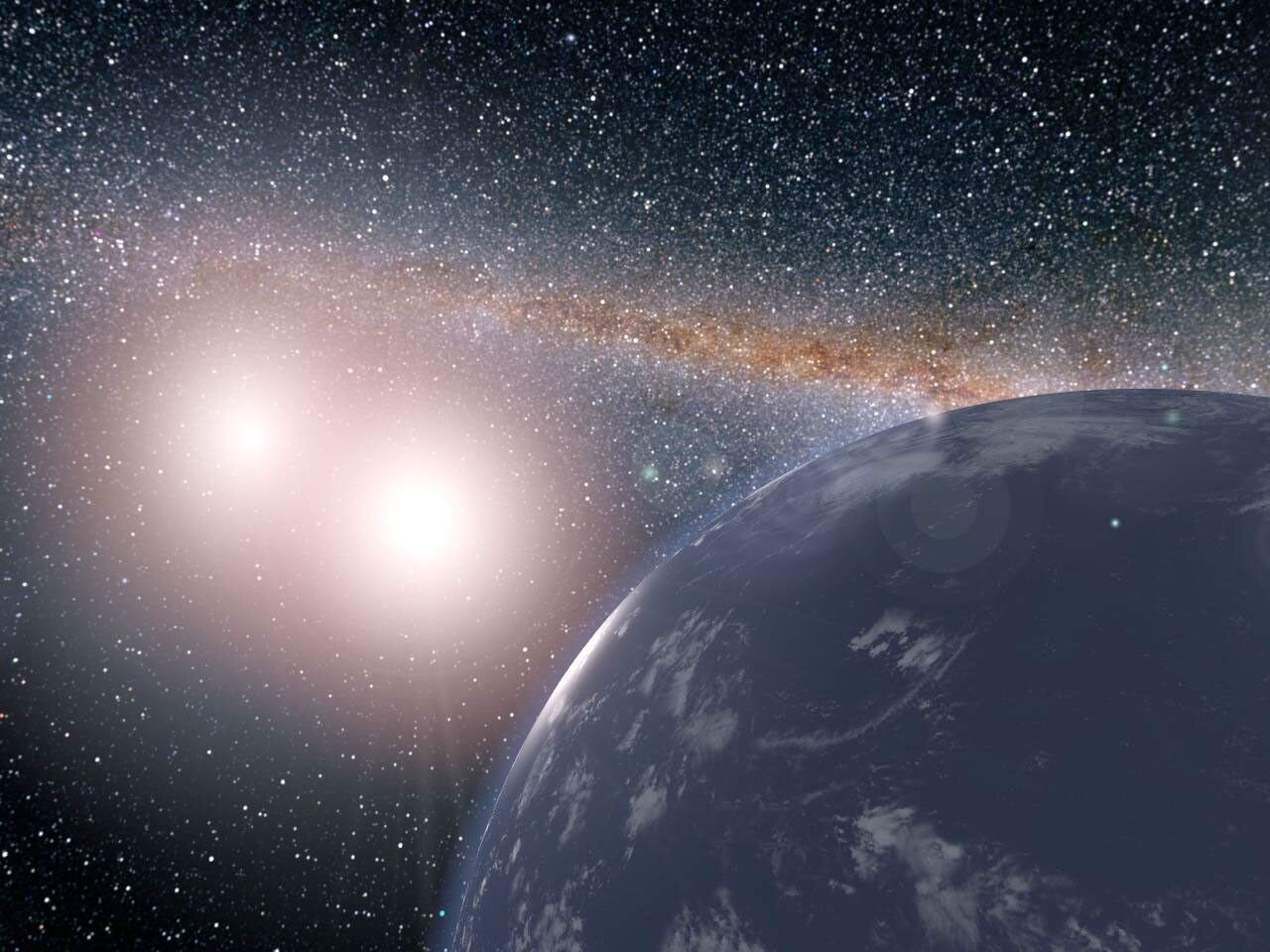

The story of the first galaxies is the story of how the universe lit up after its long night of darkness. These early galaxies were the architects of the cosmos, transforming simple clouds of gas into the complex universe we see today. They built the stars, planets, and elements necessary for life.

Thanks to modern astronomy and revolutionary telescopes like JWST, we are witnessing the dawn of everything—the birth of galaxies, the ignition of the first stars, and the moment the universe switched on its lights.

And the story is far from over. Every new observation peels back another layer of cosmic history, bringing us closer to answering humanity’s oldest question: Where did we come from?

As we peer deeper into the universe, we are looking not just at distant galaxies, but at our own origins. The first galaxies are the ancestors of everything—our Milky Way, our solar system, and even us.

They are the universe’s first light—and they illuminate the path to understanding our place in the cosmos.