For decades, the image of megalodon has loomed large in our collective imagination—a monstrous version of today’s great white shark, a bulked-up, torpedo-shaped beast with an endless appetite for destruction. Hollywood made it even more vivid, with films like The Meg painting the prehistoric predator as a super-sized great white, chomping its way through whales and ships alike.

But what if we’ve been picturing it all wrong?

A groundbreaking new study, published in Palaeontologia Electronica, flips that popular image on its head. Instead of a chunky, missile-shaped killer, researchers suggest megalodon was actually long and sleek, with a body more akin to a lemon shark—or even a massive whale—designed for gliding efficiently through the oceans. In fact, the new model of megalodon suggests it was a whopping 80 feet long (think two school buses end-to-end) and weighed around 94 tons—comparable to a modern blue whale. But it wasn’t built for constant high-speed chases. Instead, it was a master of energy-efficient cruising, patiently patrolling the seas.

Beyond the Teeth: How Scientists Got to the Truth of Megalodon’s Shape

For years, our mental picture of megalodon was largely built around its teeth. After all, megalodon teeth are some of the most impressive fossils ever found—serrated, triangular blades bigger than a human hand. Paleontologists have traditionally used tooth size to estimate body size. The thinking went like this: megalodon teeth resemble those of a great white, so megalodon must have looked like a great white—just much, much bigger.

But that assumption, it turns out, wasn’t entirely scientific. It was convenient, but not accurate.

Enter the team of researchers from the University of California, Riverside (UCR), and several institutions worldwide. They approached the problem differently. Instead of focusing on teeth, they examined megalodon’s vertebrae—the spine. They compared its vertebral column with those of more than 100 species of modern and ancient sharks. By studying proportions and growth patterns, they were able to reconstruct a much more accurate idea of the shark’s full-body anatomy.

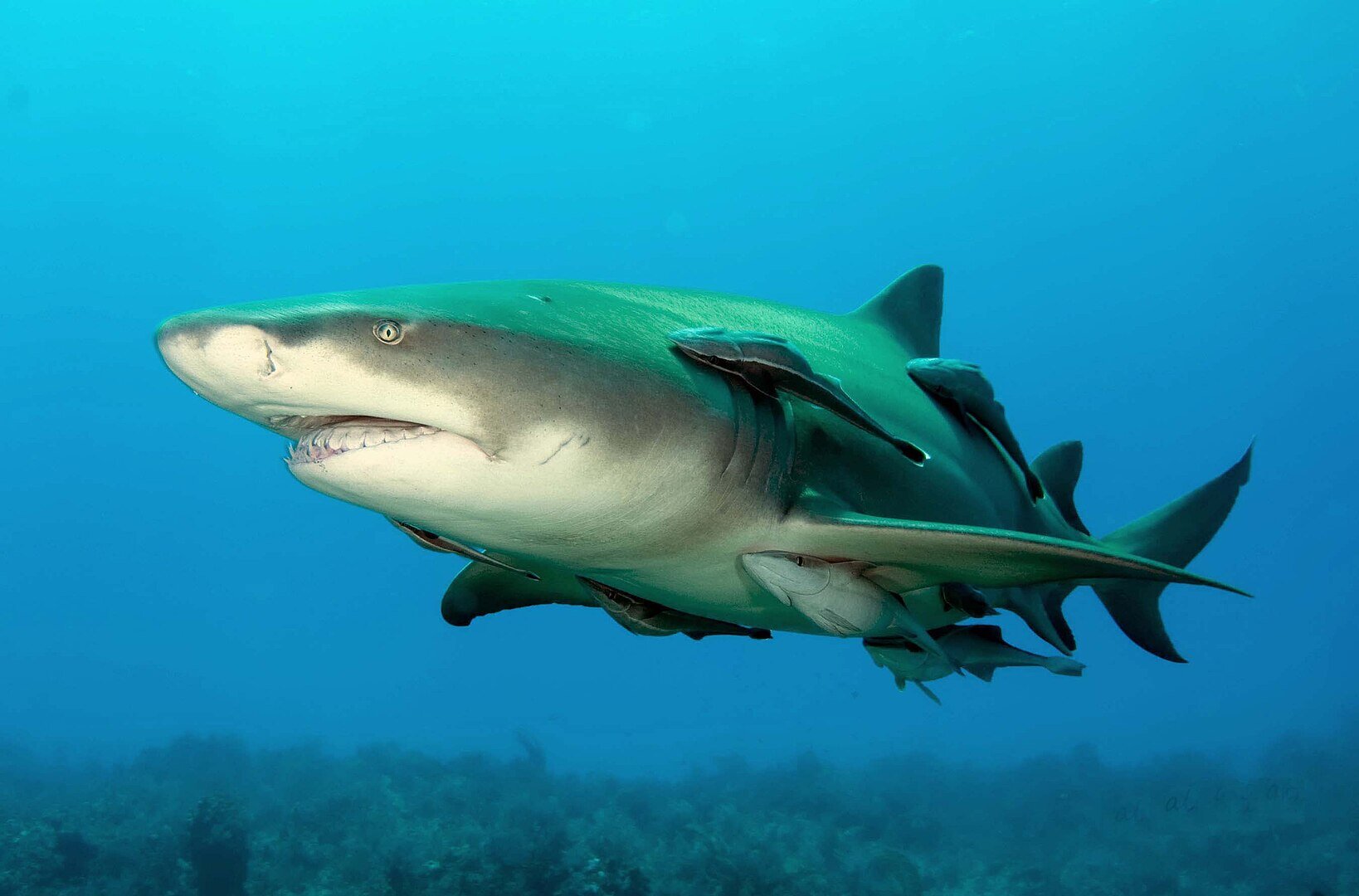

What they found was surprising. Rather than resembling an oversized great white, megalodon seemed to share more in common with the lemon shark, a sleeker, more elongated species known for its efficiency in the water. Scaling up the proportions of a lemon shark to megalodon’s immense size produced a nearly perfect fit.

“This study provides the most robust analysis yet of megalodon’s body size and shape,” said Phillip Sternes, a shark biologist who completed his Ph.D. at UCR and one of the study’s lead researchers. “Rather than resembling an oversized great white shark, it was actually more like an enormous lemon shark, with a more slender, elongated body. That shape makes a lot more sense for moving efficiently through water.”

The Science Behind the Shape: Why Streamlining Matters

The team’s findings align with a principle that’s as true in nature as it is in engineering: efficiency rules. Whether it’s a shark, a dolphin, an airplane, or an Olympic swimmer, reducing drag is key to moving quickly and easily through water (or air).

“You lead with your head when you swim because it’s more efficient than leading with your stomach,” said Tim Higham, a UCR biologist who contributed to the study. “Similarly, evolution moves toward efficiency, much of the time.”

Great whites, built like torpedoes with broad, powerful bodies, are designed for short bursts of speed to ambush their prey. But megalodon was in a league of its own. At nearly 80 feet and 94 tons, it faced different evolutionary pressures. Its bulk demanded a design optimized for energy conservation. Swimming fast all the time simply wasn’t feasible. Instead, megalodon likely cruised at moderate speeds, conserving energy for explosive bursts when it was time to strike.

And this body plan wasn’t unique. The researchers point out that large marine animals—from modern whales to extinct marine reptiles—tend to follow the same general blueprint. “The physics of swimming limit how stocky or stretched out a massive predator can be,” Higham explained.

Not a Great White 2.0—But Something Even More Impressive

If megalodon’s true body shape was closer to a lemon shark than a great white, it changes everything about how we imagine it moving through its ancient seas. Lemon sharks have a longer, more cylindrical body shape. Instead of bulging in the middle like a great white, their body tapers more gently. That streamlined form reduces resistance in the water, letting them glide smoothly and efficiently.

Now, scale that up to 80 feet. Instead of the bulky, muscle-bound predator of popular lore, picture a leaner, more graceful hunter—still terrifying in its size and power, but moving with the slow, unstoppable momentum of a freight train.

“This research not only refines our understanding of what megalodon looked like, but it also provides a framework for studying how size influences movement in marine animals,” Sternes said.

Baby Giants: Megalodon Pups Were Born Big and Ready to Hunt

Another jaw-dropping insight from the study? Megalodon babies were enormous from the get-go. Researchers estimate newborn megalodons could have been nearly 13 feet long—about the size of a fully grown great white shark today.

“It is entirely possible that megalodon pups were already taking down marine mammals shortly after being born,” Sternes noted.

Imagine a newborn predator, already large enough to prey on dolphins or small whales. It’s a chilling thought, but it fits with megalodon’s status as one of the ocean’s top predators. And starting life at such an advanced size may have given juvenile megalodons a major survival advantage, protecting them from other predators and ensuring they had a steady food supply.

Rethinking Megalodon’s Role in Its Ecosystem

With this new, more accurate body plan in mind, scientists can better understand megalodon’s place in its ecosystem. As a massive, energy-efficient cruiser, megalodon would have patrolled vast stretches of ocean in search of prey. Its diet likely included large marine mammals such as whales and seals, as well as giant fish and smaller sharks.

Unlike great whites, which favor ambush tactics, megalodon may have relied more on sustained swimming and surprise attacks delivered from below or behind. Its large size and streamlined body would have allowed it to travel long distances in search of food, covering entire ocean basins as it hunted.

And, much like modern apex predators, megalodon would have played a crucial role in maintaining balance in its ecosystem—controlling populations of large prey species and shaping the evolutionary paths of other marine animals.

The Limits of Gigantism: Why Megalodon Was an Extreme Example

One of the biggest questions in evolutionary biology is: why do some animals evolve to such enormous sizes, while others do not? The new study offers fresh insight.

“Gigantism isn’t just about getting bigger—it’s about evolving the right body to survive at that scale,” Sternes explained. “And megalodon may have been one of the most extreme examples of that.”

Being gigantic comes with serious challenges: finding enough food, maintaining efficient movement, and reproducing successfully. Megalodon managed to overcome these challenges for millions of years, dominating the oceans during the Miocene and Pliocene epochs before going extinct around 3.6 million years ago.

Scientists still debate exactly why megalodon vanished. Some theories suggest climate change, declining prey populations, and competition from other predators (including early orcas) may have contributed to its downfall. But one thing is clear: megalodon was a marvel of evolutionary engineering, pushing the limits of what was possible in the marine world.

A New Chapter in Megalodon’s Story

This study marks a turning point in our understanding of megalodon. It strips away the myths and assumptions that have built up over decades and replaces them with science-based insight into what this ancient predator was really like.

No, it wasn’t just a great white on steroids. It was something else entirely: a sleeker, more refined predator designed by evolution to rule the ancient oceans.

And while megalodon is long gone, its story still captures our imagination—reminding us of the extraordinary creatures that once swam the seas, and the mysteries that science continues to uncover.

So, the next time you picture megalodon, forget the bulky monster of Hollywood fame. Instead, imagine a streamlined, whale-sized shark, gliding effortlessly through ancient oceans—an apex predator perfectly built for its time.