Imagine peering through a giant magnifying glass, one powerful enough to bring into focus galaxies billions of light-years away. Now imagine that this magnifying glass isn’t crafted by human hands but by the universe itself. Welcome to the world of gravitational lensing, a mind-bending consequence of Einstein’s theory of general relativity and one of nature’s most astonishing tricks. It’s as if space itself turns into a lens, bending light and revealing secrets we otherwise wouldn’t be able to see.

Gravitational lensing isn’t just a theoretical curiosity. It’s an essential tool for astronomers, a cosmic magnifier that helps us study distant galaxies, measure the mass of invisible dark matter, and even detect planets orbiting stars trillions of miles away. In this story, we’ll journey through the strange world of warped space, bent light, and how gravity reshapes our view of the cosmos.

The Genius Behind the Lens: Einstein’s Bold Vision

To understand gravitational lensing, we have to begin with Albert Einstein and his revolutionary theory of general relativity, published in 1915. Before Einstein, Isaac Newton ruled supreme in explaining gravity. Newton described it as a force between two masses—simple, elegant, and practical for most everyday scenarios. But there was a problem. Newton’s gravity couldn’t explain certain strange phenomena, like the peculiar orbit of Mercury or how light could be affected by gravity.

Einstein turned everything upside down. Instead of viewing gravity as a force, he described it as the warping of spacetime itself. Imagine spacetime as a giant, invisible rubber sheet. When you place something massive on it, like a star or planet, the sheet curves. Smaller objects—or even beams of light—that pass nearby are forced to follow these curves. Einstein’s insight was radical, but it explained the universe far better than Newton ever could.

Einstein predicted that light from a distant star or galaxy passing near a massive object, like another star or galaxy cluster, wouldn’t travel in a straight line. It would bend. This bending of light by gravity is what we now call gravitational lensing.

The First Test: A Star is Born

Einstein initially believed that gravitational lensing would be almost impossible to observe. But in 1919, during a total solar eclipse, British astronomer Sir Arthur Eddington proved him wrong. Eddington and his team measured the positions of stars that appeared close to the Sun during the eclipse. They discovered that the stars’ light had been bent by the Sun’s gravity, shifting their apparent positions ever so slightly. It was one of the first major confirmations of general relativity and made Einstein a global celebrity.

But that was just the beginning.

What is Gravitational Lensing?

At its core, gravitational lensing is the bending of light caused by massive objects in space. But this bending isn’t just a simple curve—it can create arcs, rings, multiple images, and magnifications that turn the universe into a cosmic funhouse mirror.

Gravitational lenses come in different strengths and flavors, depending on the mass of the object doing the lensing and the alignment of the source, lens, and observer. Let’s break them down.

1. Strong Gravitational Lensing: The Cosmic Kaleidoscope

Strong gravitational lensing occurs when the alignment is perfect (or nearly so), and the intervening mass is enormous—like a galaxy or a cluster of galaxies. This intense gravitational field bends the light dramatically, producing spectacular effects.

- Einstein Rings: If the alignment is just right, light from a distant object can be bent into a complete circle around the lensing object. These glowing halos are called Einstein Rings, a phenomenon Einstein predicted but thought unlikely to be observed. Today, thanks to powerful telescopes like the Hubble Space Telescope, we’ve spotted many of them.

- Multiple Images: In some cases, the light from a single distant galaxy or quasar can take multiple paths around the lensing object, creating two, three, or even dozens of images of the same object. These images can appear stretched, magnified, or warped into arcs and smears.

One famous example is Einstein’s Cross, where the light from a quasar is split into four separate images surrounding a foreground galaxy.

2. Weak Gravitational Lensing: The Subtle Stretch

Weak gravitational lensing happens when the gravitational field is less intense or the alignment isn’t perfect. It doesn’t produce rings or multiple images, but it still distorts the shapes of background galaxies in subtle ways. If you look at a field of distant galaxies and notice they all seem stretched in a similar direction, you’re likely seeing weak lensing at work.

Astronomers use weak lensing to map the distribution of dark matter in the universe. Because dark matter doesn’t emit light, we can’t see it directly—but we can see its gravitational effects on the light from distant galaxies. By measuring these tiny distortions across the sky, scientists create vast maps showing where dark matter lurks.

3. Microlensing: The Blink of a Star

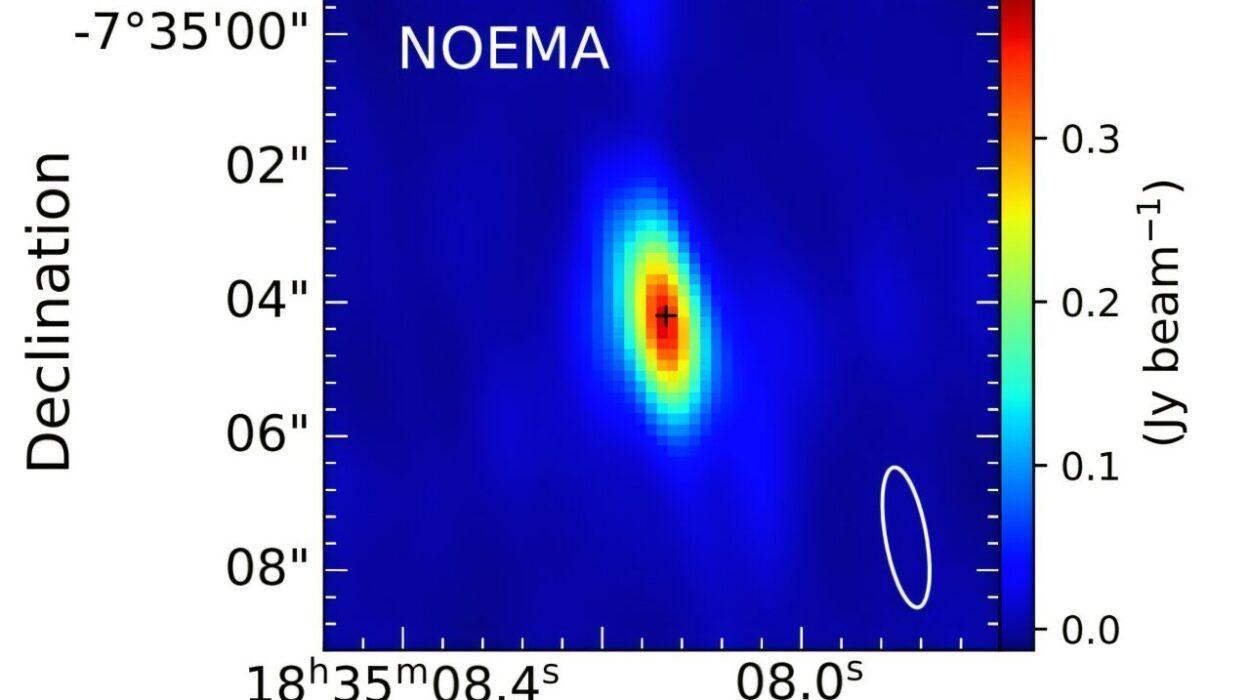

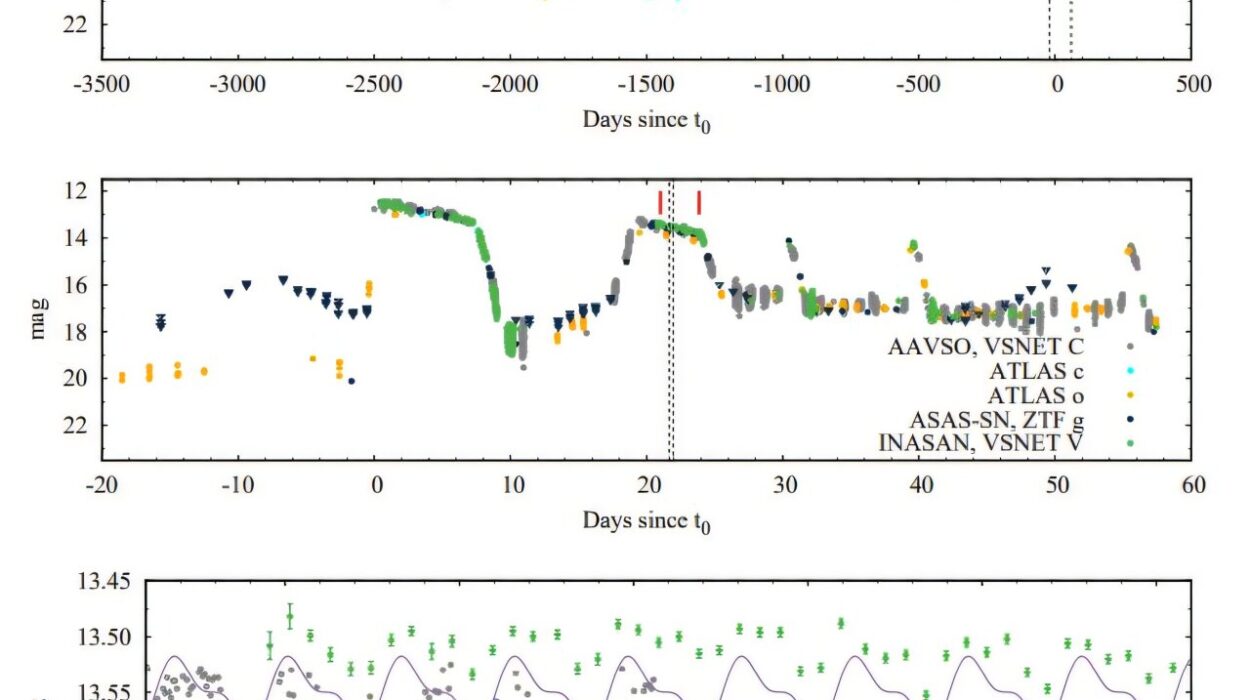

Microlensing is the smallest and most delicate form of gravitational lensing. It happens when a single star or planet passes in front of another star, magnifying its light temporarily. There’s no image distortion here—just a brief brightening.

Microlensing has been used to discover exoplanets, planets orbiting other stars. When a star with an orbiting planet passes in front of another star, both objects act as lenses, and the light curve changes in a very specific way. By analyzing these changes, astronomers have detected planets that are impossible to spot with other methods.

The Science Behind the Show: How Gravitational Lensing Works

Spacetime Curvature and Light Paths

Einstein’s theory tells us that mass bends spacetime, and light follows the curves of spacetime. When a massive object lies between us and a distant light source, it creates a gravity well, bending the path of the light rays traveling toward us. The stronger the gravity, the more the light bends.

Fermat’s Principle: The Path of Least Time

Light always takes the path that requires the least time, even if that path isn’t straight. In a gravitational lens, light can reach us by several different routes around the lensing object, each taking a different amount of time. That’s why some gravitationally lensed objects show time delays between multiple images. We can actually watch the same event play out multiple times, as light from one image reaches us sooner than from another.

Magnification: Nature’s Telescope

Gravitational lenses can magnify distant objects, making them appear brighter and larger. This magnification has allowed astronomers to study galaxies that existed when the universe was just a few hundred million years old—objects so distant and faint that they would otherwise be impossible to see.

Why Gravitational Lensing Matters

Gravitational lensing isn’t just a curiosity—it’s one of the most powerful tools astronomers have for exploring the universe.

1. Probing the Invisible: Dark Matter and Dark Energy

One of the greatest mysteries in modern astrophysics is dark matter, an invisible substance that makes up about 27% of the universe’s mass-energy content. Dark matter doesn’t emit, absorb, or reflect light, but it exerts gravity. Gravitational lensing helps us map where dark matter is concentrated, showing us the skeleton of the cosmic web that holds galaxies together.

Even more mysterious is dark energy, which drives the accelerated expansion of the universe. By measuring how gravitational lensing changes over vast cosmic distances, astronomers are gathering clues about the nature of dark energy and how it shapes the fate of the universe.

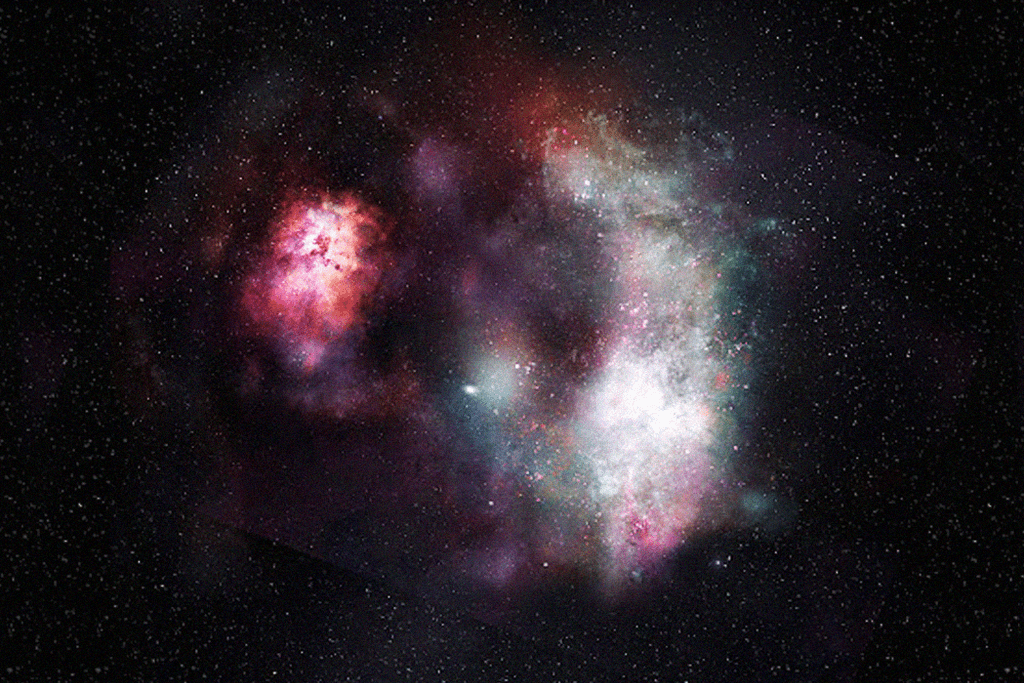

2. Studying Distant Galaxies and the Early Universe

Gravitational lenses act like natural telescopes, magnifying light from galaxies that are incredibly far away. With this magnification, astronomers can study galaxies that existed just a few hundred million years after the Big Bang. These are the building blocks of modern galaxies, and learning about them helps us understand how the universe evolved.

One spectacular example is the Hubble Frontier Fields program, which used massive galaxy clusters as gravitational lenses to peer deeper into space and time than ever before. The results have been breathtaking: images of galaxies from when the universe was still in its infancy.

3. Detecting Exoplanets and Rogue Planets

Microlensing has been a valuable tool in the search for exoplanets, especially those that are far from their parent stars or even free-floating “rogue planets” that drift through space. These rogue worlds don’t emit light and are nearly impossible to find, but microlensing events give us a way to detect them as they briefly magnify background stars.

4. Measuring the Hubble Constant

Gravitational lensing can also help solve one of astronomy’s great puzzles: the exact rate at which the universe is expanding, known as the Hubble constant. By measuring time delays between multiple images of a gravitationally lensed quasar, astronomers can calculate distances with incredible precision. These measurements contribute to the ongoing debate about the true value of the Hubble constant—and whether our current understanding of cosmology needs an overhaul.

Gravitational Lensing in Action: Some Famous Examples

Einstein’s Cross (Q2237+030)

Discovered in 1985, Einstein’s Cross is one of the most famous examples of gravitational lensing. A distant quasar, located 8 billion light-years away, is lensed by a foreground galaxy only 400 million light-years away. The light from the quasar is split into four distinct images arranged in a cross-like pattern around the lensing galaxy. It’s a striking visual confirmation of Einstein’s predictions.

Abell 370 and the Dragon

Abell 370 is a massive cluster of galaxies that lies about 4 billion light-years away. It’s one of the most famous gravitational lenses because it produces stunning arcs and smears of light from background galaxies, including a feature known as “the Dragon,” a bright, curved streak of light that represents a single distant galaxy stretched and magnified by the cluster’s gravity.

MACS J1149.5+2223 and the Reappearing Supernova

In 2014, astronomers spotted a gravitationally lensed supernova nicknamed “Refsdal” in the galaxy cluster MACS J1149.5+2223. Thanks to gravitational lensing and the different paths light can take around the lensing cluster, the supernova was observed multiple times as its light arrived at different intervals. This cosmic replay allowed scientists to test their models of gravitational lensing and refine their understanding of galaxy cluster mass distributions.

The Future of Gravitational Lensing: Bigger Telescopes, Deeper Insights

With the launch of new observatories like the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) and the upcoming Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, gravitational lensing research is entering a golden age. These advanced telescopes will allow astronomers to find more gravitational lenses, study fainter and more distant galaxies, and improve our understanding of dark matter and dark energy.

Ground-based surveys like the Vera C. Rubin Observatory’s Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST) will provide a massive dataset for discovering weak lensing effects across the entire sky. This data will help answer some of the biggest questions in cosmology, such as the nature of dark energy and the shape of the universe.

Conclusion: A Universe Revealed

Gravitational lensing is more than just a quirk of physics—it’s one of nature’s greatest gifts to astronomers. Like a cosmic magnifying glass, it allows us to see deeper, further, and clearer than ever before. It’s a stunning confirmation of Einstein’s vision, a window into the unseen realms of dark matter and dark energy, and a key to unlocking the mysteries of the cosmos.

As our telescopes and understanding grow ever more powerful, gravitational lensing will continue to reveal the wonders of the universe in ways Einstein himself might never have imagined. In the warping of light by gravity, we find a beautiful metaphor: that even the darkest corners of space can be illuminated when we look at them through the right lens.