For over a century, archaeologists and paleoanthropologists have uncovered curious spherical stones scattered across ancient hominin sites in Africa, Europe, and Asia. These enigmatic objects—dubbed stone balls, spheres, spheroids, and even bolas—have long fueled speculation. Were they primitive weapons? Percussion tools? Or perhaps prehistoric projectiles flung at prey? Their perfectly rounded forms sparked endless debate. But a groundbreaking new study by Dr. Margherita Mussi, recently published in Quaternary International, shifts the conversation in an entirely new direction—one that could rewrite what we know about early human behavior.

Mussi’s work at Melka Kunture, a cluster of rich archaeological sites in Ethiopia’s Upper Awash Valley, reveals an overlooked yet intriguing reality: many of these stone spheres weren’t painstakingly carved by hominins but were naturally occurring volcanic stones—simple basalt globes formed by ancient geological processes. And yet, early humans collected and used them as tools for over a million years. Why? Because sometimes, nature hands you the perfect tool. You just need the intelligence to recognize it.

Melka Kunture: A Time Capsule of Human Evolution

Situated in the heart of Ethiopia’s Rift Valley, Melka Kunture is more than just a fossil hunter’s dream. It’s a living record of humanity’s deep past. The region boasts a series of Pleistocene-era sites, layered with volcanic deposits and sedimentary archives of ancient human activity. Eruptive centers once surrounded the area, leaving behind an abundance of volcanic rock—specifically basalt.

Across eight key excavation sites—Gombore IB, Atebella II, Garba XII, Gombore II-1, Gombore II-2, Garba IIIE, Gotu III, and Garba I—archaeologists have recovered more than 30 of these basalt spheres. They range in age from 1.7 million years ago (mya) to as recently as 600,000 years ago. These stones, remarkably smooth and round, may seem ordinary at first glance. But according to Mussi’s meticulous analysis, they hold the fingerprints of early hominin ingenuity.

The Forgotten Spheres: Overlooked Clues from Our Ancestors

For decades, archaeologists have been fascinated by stone tools deliberately crafted by early humans—hand axes, scrapers, and spear points have taken center stage in our narratives about prehistoric technology. But naturally shaped stones? These were often dismissed as mere curiosities or random geological detritus. Mussi’s research changes that.

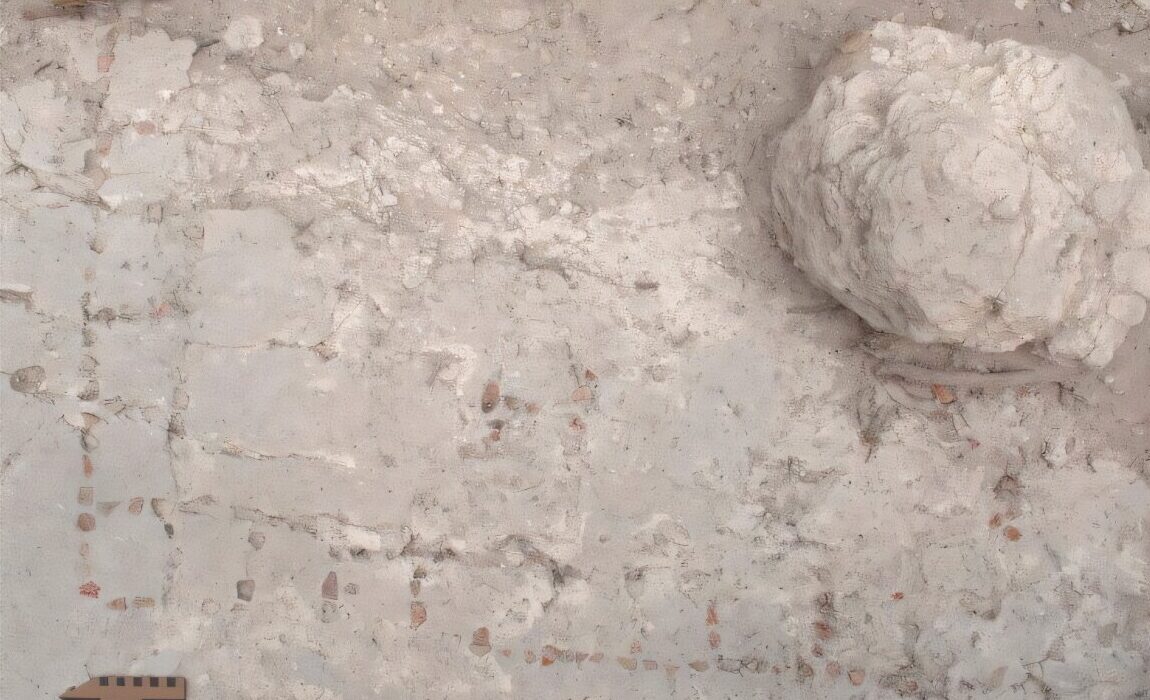

Unlike the finely chipped lithics typically found at Melka Kunture, these basalt spheres show little evidence of intentional shaping. Yet, they were consistently present across a variety of sites, many alongside thousands of other stone tools. Gombore IB alone, the oldest site, yielded nearly 5,000 lithic tools and three basalt spheres—along with two fossilized fragments of a Homo cf. ergaster humerus bone. Nearby sites like Garba III and II offered up even more spheres, accompanied by remains from Homo heidelbergensis and Homo sapiens.

These findings aren’t accidental. Mussi argues that the basalt spheres were deliberately chosen by early hominins and transported to these sites. They weren’t just lying around in streambeds or river channels. In fact, many were found in fine-grained deposits where their weight and composition stand out starkly against the surrounding sediments. This fact alone rules out water transport as their source.

“The metric characteristics, shape, and orientation of pebbles transported by water have been thoroughly researched,” Mussi explains. “Some of the sites are composed of fine-grained deposits where the relatively heavy rock spheres are at odds with the surrounding environment. And the softer lapilli stones would have been crushed during water transport.”

In other words: early humans picked these stones up, carried them, and used them—over and over again.

Nature’s Perfect Tools: Why Basalt Spheres Were So Valuable

What’s so special about these basalt spheres? According to Mussi, their value lay in their material properties and shape. The hard volcanic stones were ideal for percussion tasks—knapping or retouching other lithic tools. Their smooth, rounded surfaces made them comfortable to grip and easy to control during repetitive hammering. Meanwhile, the softer lapilli spheres could have been used for grinding, rubbing hides, or even processing plant materials.

“I am convinced that the hard volcanic ones were used to knap and retouch lithic tools, while the rather soft lapilli ones were used for rubbing vegetables, hides, or other stuff,” Mussi states.

This distinction is critical because it suggests that early hominins weren’t just randomly picking up stones—they were selecting them for specific tasks, recognizing the different properties of volcanic rocks and putting them to practical use.

Mussi refers to these objects as outils à posteriori—tools we recognize as such only after observing the signs of wear and evidence of their use. They weren’t modified by the hominins who used them; their function was dictated by the natural shape they already possessed.

A Million Years of Innovation: Tracking Hominin Cognitive Evolution

What makes this discovery truly groundbreaking is the timespan over which it occurred. At Melka Kunture, these naturally occurring stone spheres were collected and used consistently for over one million years—across multiple hominin species, in changing climates and landscapes.

Mussi believes this reflects something profound about human evolution. As different hominin species came and went—from Homo erectus to Homo heidelbergensis, and eventually Homo sapiens—they continued to recognize the utility of these basalt spheres. In doing so, they demonstrated an ability to adapt to their environment, selecting the best tools nature had to offer, and using them effectively.

“It is possibly the first evidence of the use of natural shapes for varied activities, and this happened repeatedly over more than 1 million years of human evolution at Melka Kunture,” Mussi explains. “While hominin species were changing from Homo erectus to H. heidelbergensis, the round rocks were selected from various sources in a changing environment. In my opinion, this is good evidence of how the hominins were carefully exploiting any new resource and cleverly using them.”

A New Chapter in the Story of Human Tool Use

Mussi’s study is a powerful reminder that not all human innovation lies in our ability to reshape the world. Sometimes, intelligence lies in recognizing what’s already there—and putting it to work.

In today’s age of advanced technology, it’s easy to forget that the earliest tools weren’t always fashioned by hand. They were found in the world around us and used as-is. This kind of opportunistic tool use reveals a nuanced intelligence in early hominins, one that’s often overlooked when we focus solely on artifacts that show clear signs of human workmanship.

The discovery of these spheres and their deliberate use opens up new avenues for understanding early human behavior. It prompts researchers to reconsider other naturally occurring materials that might have played crucial roles in prehistory—materials that may have gone unnoticed because they didn’t fit the traditional definition of a “tool.”

Conclusion: Rethinking Human Ingenuity

Dr. Margherita Mussi’s work at Melka Kunture shines a light on a subtle but vital chapter of human evolution. The basalt spheres, once thought to be incidental geological oddities, are now seen as silent witnesses to our ancestors’ ingenuity.

Their story stretches back over a million years—a testament to hominin adaptability, resourcefulness, and cognitive development. Long before the invention of the hand axe or the bow and arrow, early humans were making sophisticated decisions about which objects to collect and how to use them. They understood the value of a smooth, dense rock, and they returned to these tools again and again as they evolved.

In the grand tapestry of human history, these seemingly humble spheres represent a quiet revolution—one that shows how the simplest tools, when chosen wisely, can shape the destiny of a species.

As researchers continue to explore Melka Kunture and sites like it, one thing becomes clear: our ancestors were far more resourceful than we ever imagined. And sometimes, all it takes to uncover their brilliance is a closer look at the stones beneath our feet.

Reference: Margherita Mussi, The volcanic rock spheres of Melka Kunture (Upper Awash, Ethiopia) at Gombore IB and later Acheulean sites, Quaternary International (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.quaint.2025.109681