What if the choices you make in your forties and fifties—whether it’s reaching for a salad over a burger, or finding time for a brisk walk instead of settling into the couch—could shape how sharp your mind stays decades later? A new study, published in JAMA Network Open, suggests precisely that.

Researchers from Oxford University, University College London, and collaborating institutions across Europe have uncovered compelling evidence linking midlife diet quality and body composition with brain health in later years. Their findings hint at a simple but powerful truth: what’s on your plate, and where you store your fat, may influence how well your brain connects and performs as you age.

The study draws from the rich data of the Whitehall II Study, a long-term investigation that has followed over 10,000 British civil servants since the mid-1980s. This new analysis, focusing on brain imaging and cognitive assessments of a subset of participants, marks an important step forward in understanding how lifestyle choices in midlife ripple through to old age.

A Shift in How We Think About Brain Health

Traditionally, much of the research on diet and brain function zeroed in on isolated nutrients—think omega-3s, antioxidants, or vitamins. But real life doesn’t happen one nutrient at a time. We eat meals, not molecules. Likewise, much of the earlier research has focused on late-life interventions, which might be too little, too late.

This new study takes a different tack, offering a broader, more holistic view. It highlights overall dietary patterns and abdominal obesity, measured over two decades, and ties them to brain connectivity and cognitive performance later in life.

The Whitehall II Advantage

The Whitehall II Imaging Substudy, conducted at Oxford between 2012 and 2016, recruited over 500 individuals for brain scans and cognitive tests. Participants were in their early seventies at the time of imaging—but their lifestyle and health data stretched back to middle age. This allowed the researchers to look at how long-term patterns of diet and body fat distribution related to brain health in older age.

Two Key Measures:

- Diet Quality, evaluated using the Alternative Healthy Eating Index–2010 (AHEI-2010). This score assesses how closely an individual’s diet aligns with healthy eating guidelines—favoring vegetables, fruits, whole grains, nuts, and minimizing red meat, sugar, and unhealthy fats.

- Waist-to-Hip Ratio, a well-known measure of abdominal obesity, recorded five times over a 21-year period.

The Brain: A Network That Needs Nourishing

The researchers focused on brain connectivity—how different regions of the brain communicate with one another—and white matter integrity, the brain’s internal wiring. These features are critical for memory, decision-making, focus, and problem-solving.

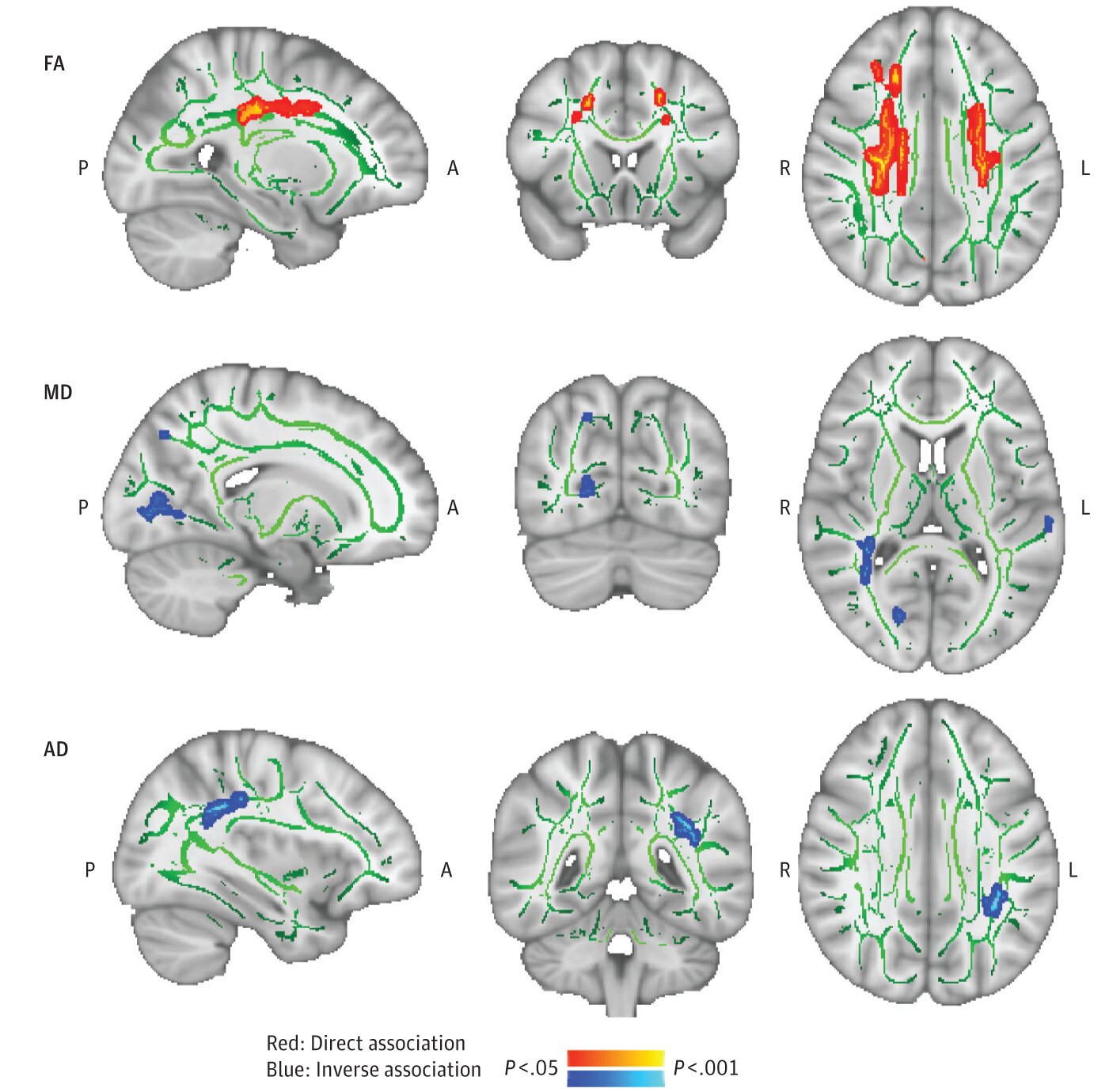

Using advanced MRI techniques, including diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) and resting-state functional MRI (fMRI), they were able to peer into the architecture of the aging brain. What they found was illuminating.

Healthy Diet, Stronger Brain

People who maintained a higher-quality diet through midlife had better white matter integrity and stronger connections between key areas of the brain involved in memory and thinking. Specifically:

- Improved hippocampal connectivity, which plays a key role in memory formation, was observed, especially between the hippocampus, occipital lobe, and cerebellum.

- Better white matter integrity, reflected in higher fractional anisotropy and lower mean diffusivity, suggested healthier, more robust brain wiring.

These structural and functional advantages translated into sharper cognitive performance—particularly in working memory and executive function, the brain’s ability to plan, focus, and juggle multiple tasks.

Abdominal Fat: A Red Flag for Brain Aging

On the flip side, a higher waist-to-hip ratio—a sign of carrying more fat around the abdomen—was linked to widespread declines in white matter integrity. Some of the most affected brain regions included:

- The cingulum, involved in attention and memory.

- The inferior longitudinal fasciculus, linked to object recognition and memory processing.

Greater mean diffusivity and radial diffusivity—both indicators of declining white matter health—were observed in participants with higher waist-to-hip ratios. This deterioration was, in turn, tied to poorer cognitive performance.

In Simple Terms: Carrying excess belly fat in midlife doesn’t just raise risks for heart disease and diabetes—it’s also a warning sign for brain aging.

Why Midlife Matters

One of the most striking takeaways from the study is the importance of when we act. The midlife years—roughly ages 40 to 65—emerge as a critical window for brain health interventions.

“Midlife is when the seeds of later-life brain health are planted,” notes lead researcher Dr. Mika Kivimäki of University College London. By the time we reach our seventies or eighties, it may be much harder to reverse damage already done.

What Does This Mean for Dementia Prevention?

This study adds weight to the idea that prevention, not treatment, should be the cornerstone of strategies to combat dementia and age-related cognitive decline.

In a commentary published alongside the research, Dr. Sharmili Edwin Thanarajah from Goethe University Frankfurt called attention to the global public health challenge these findings pose. With 43% of adults and 20% of children now classified as overweight or obese worldwide, a major barrier to improving cognitive outcomes is the modern food environment itself.

“It’s not just about personal willpower,” Thanarajah argues. Systemic changes—from improving access to healthy foods, regulating marketing of junk foods, to urban design that encourages physical activity—are needed to support healthier choices.

What About Sex Differences?

One notable gap in the research is its gender imbalance: only 20% of participants were women. This leaves open important questions about whether the findings apply equally to women.

Women and men often have different fat distribution patterns, hormonal influences, and possibly different aging trajectories when it comes to brain structure. Future studies, researchers suggest, should aim for better gender balance and investigate sex-specific effects on diet, obesity, and brain health.

The Role of Alcohol: A Complicated Relationship

Another wrinkle in the findings involves alcohol consumption. In the study cohort, heavier drinking was associated with poorer diet quality, and alcohol itself has been linked to white matter damage, vascular problems, and inflammation—all factors that can accelerate cognitive decline.

While this study couldn’t disentangle the direct effects of alcohol from those of diet and body fat, it underscores the need for more nuanced research into how alcohol fits into the larger picture of brain aging.

What’s Next?

While observational studies like this one reveal powerful associations, they stop short of proving cause and effect. The next big step? Intervention trials that test whether improving diet quality or reducing abdominal fat in midlife can actually change the course of brain aging.

“Proving causality would be a game-changer,” says Dr. Kivimäki. “It would give policymakers, clinicians, and individuals strong reasons to act sooner rather than later.”

What You Can Do Now

While scientists continue to untangle the complex relationships between diet, body fat, and brain health, the take-home messages from this study are refreshingly clear:

- Prioritize a healthy diet, rich in vegetables, fruits, whole grains, lean proteins, and healthy fats. The Mediterranean or DASH diets are great starting points.

- Maintain a healthy waistline, especially avoiding excess abdominal fat. Regular exercise—both aerobic and strength training—plays a key role here.

- Limit alcohol and be mindful of its potential impact on both diet quality and brain health.

- Act early. Your brain in old age may very well depend on the choices you make in midlife.

A Brighter, Sharper Future?

In a world where the global burden of dementia is expected to triple by 2050, studies like this offer hope. By understanding—and acting on—the links between midlife health and brain aging, we may be able to extend not only lifespan but healthspan, keeping minds sharper for longer.

As Einstein (a master of midlife wisdom) once said, “The distinction between past, present and future is only a stubbornly persistent illusion.” Perhaps the brain health choices we make now aren’t just for the future—they’re shaping our lives in the present as well.

References: Daria E. A. Jensen et al, Association of Diet and Waist-to-Hip Ratio With Brain Connectivity and Memory in Aging, JAMA Network Open (2025). DOI: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2025.0171

Sharmili Edwin Thanarajah, Midlife Dietary Quality and Body Composition Relevance for Brain Connectivity and Cognitive Performance in Later Life, JAMA Network Open (2025). DOI: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2025.0181