In the vast cosmic ocean, countless worlds orbit their parent stars in an orderly dance, bound by gravity’s invisible thread. Planets like Earth, Mars, and Jupiter are tethered to the Sun, circling their life-giving star like loyal companions. Yet, somewhere beyond the familiar light of these stellar families, there exists a darker, lonelier realm—one populated by wanderers. These are the rogue planets, orphan worlds cut loose from the stars that once cradled them. Homeless, they drift endlessly through the interstellar void, alone in the darkness. They are the cosmic nomads, lost children of the galaxy.

What are these strange worlds? Where did they come from? How do we find something that, by its very nature, shuns the light? Hunting rogue planets is one of the great scientific challenges of our time—a cosmic treasure hunt played out on the grandest scale imaginable. It pushes the limits of our technology and understanding, forcing us to peer into the deepest shadows of the universe. Yet what we find there could fundamentally change how we see planetary systems—and perhaps even offer new possibilities for life in the cosmos.

In this deep dive into the mystery of rogue planets, we’ll explore what they are, how they form, why they matter, and how humanity is developing the tools to track them across the stars. So tighten your spacesuit and charge your curiosity—we’re heading out into the dark.

What Are Rogue Planets?

Rogue planets—also called free-floating planets or nomad planets—are planetary-mass objects that wander the galaxy without orbiting a star. Imagine Jupiter or Earth, but without the Sun. These objects roam alone, unattached, moving through the darkness of interstellar space. Devoid of any central sun to bathe them in warmth and light, they are some of the coldest, loneliest objects in the universe.

Some rogue planets may have once orbited stars, only to be flung away by violent gravitational encounters—either with another massive planet or as a result of the chaos of young planetary systems still finding their stability. Others may have formed in isolation, collapsing from clouds of gas and dust too small to ignite nuclear fusion, the process that makes stars shine.

For centuries, rogue planets existed purely in the realm of theory. After all, how do you find something that doesn’t shine? But science has caught up with imagination, and over the past few decades, astronomers have discovered increasing evidence that these lonely worlds are not just possible—they are common. Some estimates suggest there may be as many rogue planets in our galaxy as there are stars—possibly even more.

The Formation of Cosmic Orphans

How do planets become rogues? There are two primary schools of thought—both fascinating, both violent.

1. Ejection from Planetary Systems

The most common theory is planetary ejection. Picture a young star system, still in its infancy. Planets are forming from the disc of gas and dust spinning around the newborn star. As these planets take shape, they jockey for position, their gravitational fields interacting, tugging at each other in a cosmic game of tug-of-war.

Sometimes, one planet gets too close to another. A massive planet, like a gas giant, can gravitationally slingshot its smaller sibling right out of the system. Other times, the star itself might interact with another star, passing close enough to destabilize the orbits of its planets and eject them into space. These are worlds that had a home—until they were evicted.

2. Formation Without a Star

A more exotic possibility is that some rogue planets formed in isolation. Instead of condensing inside a planetary disc, they collapse directly from small clouds of gas and dust in space. These are planetary-mass objects that never had a star at all. They are born orphans.

This process blurs the line between planet and brown dwarf, objects that are too small to be stars but too large to be ordinary planets. Scientists debate whether some rogues are truly planets or if they belong to a different category altogether. But for our purposes, if it’s planet-sized and not orbiting a star, we call it rogue.

Life on a Rogue Planet?

It’s easy to assume that rogue planets are cold, dead worlds, too far from any warmth to harbor life. After all, without a star, wouldn’t they just be frozen wastelands? Maybe not.

Some rogue planets may generate enough internal heat through radioactive decay or residual heat from their formation to sustain subsurface oceans. Just as Jupiter’s moon Europa and Saturn’s moon Enceladus hide oceans beneath their icy crusts, a rogue planet might do the same on a grander scale. If life can exist around hydrothermal vents at the bottom of Earth’s oceans, without any sunlight, then maybe life could thrive in the hidden oceans of a rogue world.

Even more tantalizing is the idea of a rogue planet with a thick atmosphere of hydrogen. Hydrogen is an excellent insulator. If a rogue planet were massive enough and had a dense hydrogen envelope, it could trap heat and maintain surface temperatures suitable for liquid water—even in the cold vacuum of interstellar space.

In 1998, the science fiction novel “Rogue Planet” by Greg Bear imagined such a world: one where humans lived under a thick insulating atmosphere, warmed by the planet’s own geothermal energy. While fiction, it’s grounded in real science. Some researchers believe these “Steppenwolf planets,” as they are sometimes called, could be viable habitats for life—even complex life.

The Challenge of Discovery

Finding planets around distant stars is hard enough. Finding rogue planets, which don’t orbit a bright star and emit little to no light, is astronomically harder. It’s like searching for a black marble in a coal mine.

Gravitational Microlensing: Nature’s Magnifying Glass

One of the most powerful tools in the hunt for rogue planets is gravitational microlensing. According to Einstein’s general theory of relativity, mass bends the fabric of space-time. When a rogue planet passes between us and a background star, its gravity acts as a lens, temporarily magnifying and brightening the light from the star. The result is a brief, telltale flare that astronomers can detect.

Microlensing doesn’t require the planet to shine; it only needs to have mass. In 2011, a team led by Takahiro Sumi at Osaka University used microlensing to detect evidence of rogue planets in the Milky Way, estimating that free-floating planets could outnumber stars two to one.

But microlensing is rare and fleeting. The alignments necessary for such events are unpredictable and short-lived, often lasting just days or even hours. Catching them requires constant monitoring of millions of stars—a monumental task.

Infrared Astronomy: Seeing in the Dark

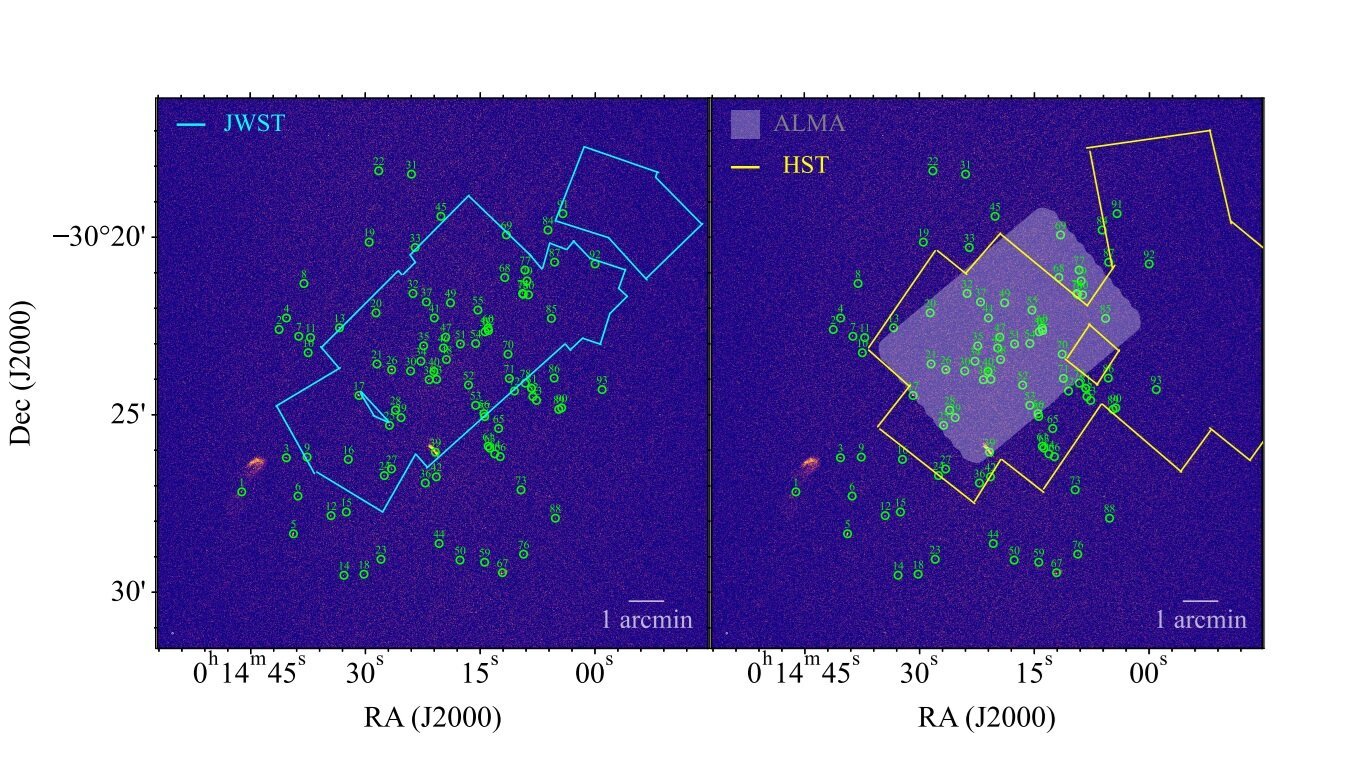

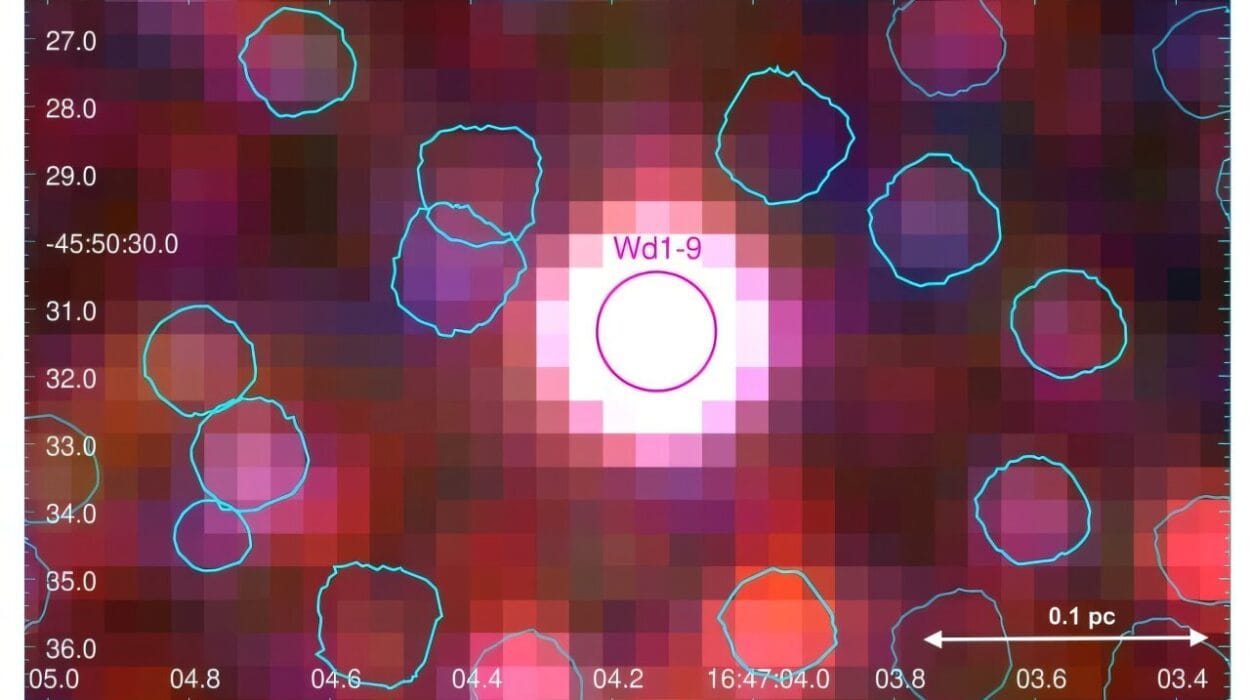

Some rogue planets, especially younger ones, are still warm from their formation. These objects emit faint infrared radiation. Telescopes like NASA’s Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) and the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) are perfectly suited to spot these warm wanderers.

In 2012, WISE discovered a rogue planet candidate named PSO J318.5-22, floating 80 light-years away. It’s about six times the mass of Jupiter and shines faintly in the infrared. Though it has no star, it’s young enough to glow dimly from residual heat.

Infrared surveys help locate the warmest rogues, but as they cool over billions of years, they fade into blackness, becoming nearly impossible to detect.

Known Rogue Planet Candidates

Over the past two decades, astronomers have identified several promising candidates for rogue planets. Here are a few of the most fascinating:

PSO J318.5-22

Discovered in 2013, PSO J318.5-22 is a lonely giant planet, about six times the mass of Jupiter. It floats 80 light-years from Earth in the constellation Capricornus. It’s relatively young—just 12 million years old—and still radiates heat from its formation, glowing faintly in infrared. Despite its size, it has no sun to call its own.

OGLE-2016-BLG-1928

This is the smallest rogue planet ever discovered through microlensing. It’s estimated to be between the mass of Mars and Earth. This tiny world was found in 2020 using data from the OGLE (Optical Gravitational Lensing Experiment) and KMTNet (Korea Microlensing Telescope Network) collaborations. It’s a tantalizing glimpse into the potential for rocky rogue planets.

CFBDSIR 2149-0403

Located about 100 light-years away, CFBDSIR 2149-0403 was initially thought to be a rogue planet roughly four to seven times the mass of Jupiter. Newer research suggests it might be a brown dwarf, but it remains one of the most studied rogue candidates.

Rogue Planets in Popular Culture

The concept of a planet drifting through space has captured the imagination of science fiction writers for decades. From wandering worlds that pass by Earth, threatening destruction, to mysterious homes for alien civilizations, rogue planets have served as eerie, romantic backdrops for cosmic storytelling.

- “Interstellar” (2014): The water world Miller’s Planet orbits close to a massive black hole, not a star. Though not a rogue planet, it hints at the kind of strange environments a planet might survive in.

- “Doctor Who” (Episode: “The End of the World”): Features a planet called Midnight, which orbits a radiation-heavy exoplanet and has no atmosphere. Again, it plays with the concept of unorthodox planetary environments.

- “Rogue Planet” (Greg Bear, 2000): This Star Wars novel imagines a world ejected from its system, surviving as a massive, intelligent organism. The title says it all.

Science fiction provides imaginative glimpses of what might be possible—and sometimes foreshadows what science eventually proves true.

The Future of Rogue Planet Hunting

As technology advances, so does our ability to hunt rogue planets. Here’s a glimpse into what’s coming:

Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope

Set to launch later this decade, NASA’s Roman Space Telescope will conduct microlensing surveys capable of detecting rogue planets down to Mars-size or smaller. Its mission could confirm whether these drifters are truly common.

James Webb Space Telescope (JWST)

JWST’s infrared capabilities make it ideal for spotting the faint glow of young rogue planets. It will study known candidates in greater detail and may discover new ones.

Ground-Based Telescopes

The Vera C. Rubin Observatory in Chile, with its Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST), will scan vast areas of the sky repeatedly. While not designed specifically for rogue planet hunting, its powerful surveys may catch transient microlensing events and help locate these elusive objects.

Why Rogue Planets Matter

Some might wonder: Why should we care about planets that drift alone in the dark?

1. Understanding Planetary Systems

Rogue planets tell us about the formation and evolution of planetary systems. Their numbers can confirm or challenge existing models of how planets form and how stable planetary systems are over time.

2. Potential Habitats for Life

If rogue planets can sustain subsurface oceans or retain warmth under thick atmospheres, they could be unexpected havens for life. The discovery of life on a rogue planet would shatter our understanding of habitability.

3. Future Human Exploration

Rogue planets close to our solar system could serve as targets for future exploration or even colonization. Though highly speculative, it’s an idea that pushes the boundaries of our imagination.

4. Cosmic Perspective

Rogue planets remind us of the vast, wild, and unpredictable nature of the cosmos. Not every world sits neatly in a solar system. Some wander, alone but not forgotten, offering a profound lesson in cosmic diversity.

Epilogue: The Lonely Light in the Dark

In the end, rogue planets are a testament to the chaotic, dynamic universe we inhabit. They drift through space in silence, untethered, unseen—yet they are there, by the billions. Each one is a mystery, a story waiting to be told. Some are frozen husks, others might harbor oceans of life beneath a thick, warming shroud. They are the ultimate wanderers, the lost children of creation.

And as humanity grows bolder in its exploration of the cosmos, we will find them. We will study them. And perhaps, one day, we will set foot on them, turning these cold, lonely places into warm new homes.

The hunt has only just begun.