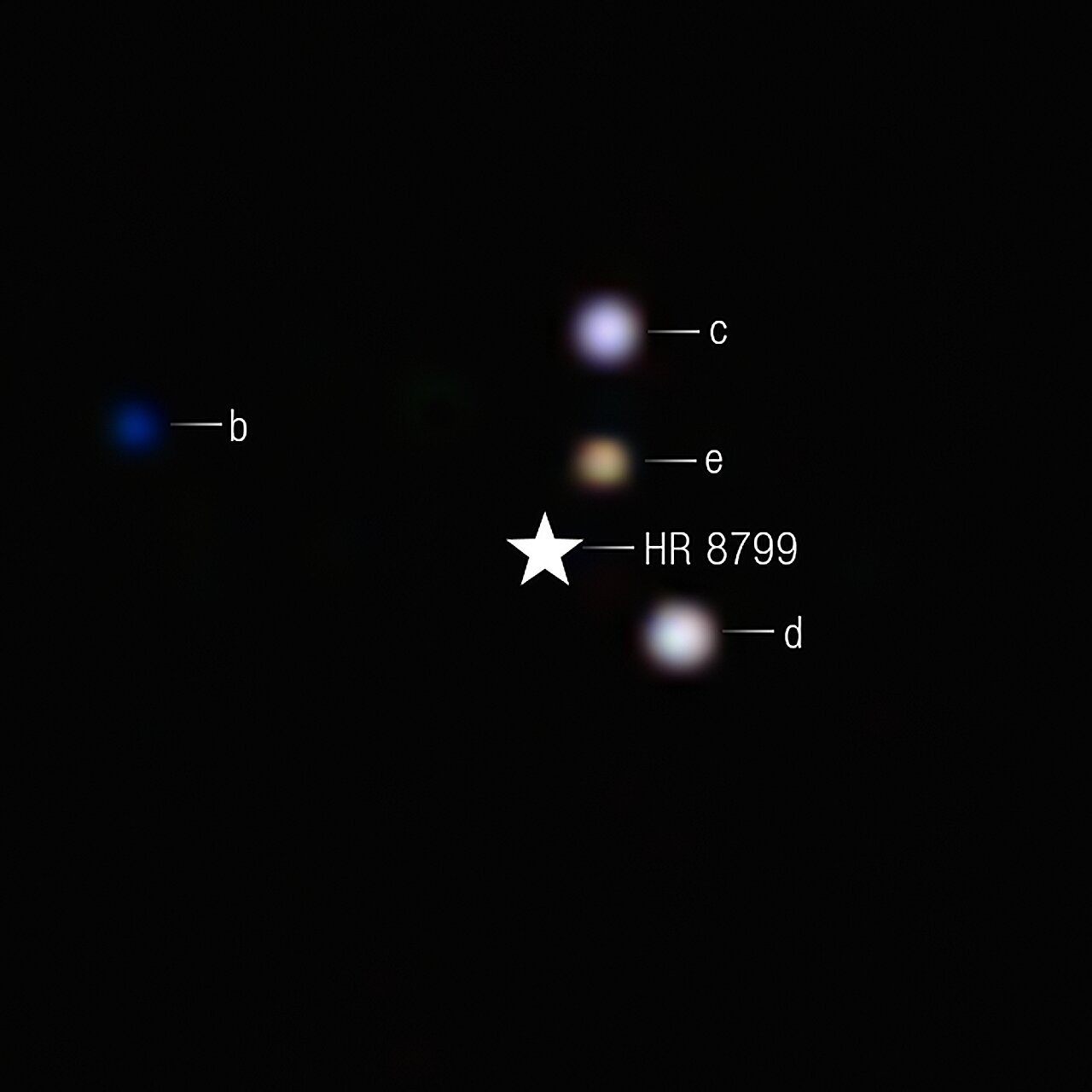

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), humanity’s most powerful eye in space, has just unveiled a groundbreaking achievement: the first direct images of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere of an exoplanet. This milestone didn’t happen in a distant, featureless gas giant, but in HR 8799—a dazzling multiplanet system located 130 light-years away. This star system has long been a cosmic laboratory for scientists eager to uncover the secrets of planet formation beyond our solar system. And now, thanks to Webb, we are closer than ever to answering some of our biggest questions about how planets, and perhaps life itself, arise.

A New Frontier in Exoplanet Exploration

Astronomers have studied HR 8799 for years. It’s a relatively young system, just 30 million years old—practically a newborn compared to our 4.6-billion-year-old solar system. Its four enormous planets, each several times more massive than Jupiter, are still radiating heat from their violent birth. But until now, most of what we knew about them came from indirect observations or broad spectral analyses. Webb has changed that.

Using its sophisticated suite of instruments, including finely tuned coronagraphs that block out the glare of the parent star (think cosmic sunglasses), JWST directly captured the chemical fingerprints of carbon dioxide in these exoplanet atmospheres. It’s like pulling back a curtain on another world and finding familiar molecules staring back at you.

“We’re seeing strong carbon dioxide features,” said William Balmer, the Johns Hopkins University astrophysicist who led the research. “This tells us these planets contain a sizable fraction of heavy elements like carbon, oxygen, and iron in their atmospheres. And when you consider the nature of the star they orbit, it suggests these planets likely formed the same way Jupiter and Saturn did—in a slow, bottom-up process called core accretion.”

Cracking the Code of Planet Formation

So why is this discovery so exciting? It’s all about understanding how these planets came to be.

Astronomers have long debated whether massive planets form by core accretion—a slow process where rocky cores gradually gather gas—or by disk instability, a rapid gravitational collapse of material in a young star’s disk. Each theory has different implications for the architecture of planetary systems and the potential for habitable worlds.

By identifying carbon dioxide directly, Webb’s data strongly supports the core accretion model for HR 8799’s four giant planets. This suggests they formed more like the gas giants in our solar system than like brown dwarfs or small stars.

“Our hope with this kind of research is to understand our own solar system, life, and ourselves in comparison to other exoplanetary systems,” Balmer explained. “Are we unique? Is our solar system a cosmic oddball, or is it pretty standard? Webb is giving us the tools to answer these questions.”

A Milestone in Direct Imaging

Directly imaging exoplanets is no easy feat. Planets are often dwarfed by the blinding light of their stars, typically shining thousands of times brighter. Previous studies using Webb and other telescopes inferred chemical compositions by watching planets pass in front of their stars, causing starlight to filter through their atmospheres—a method called transit spectroscopy. It’s powerful, but limited to systems where planets transit, or cross in front of, their stars from our vantage point.

What makes Webb’s latest accomplishment extraordinary is that it didn’t rely on a transit. Instead, Webb’s instruments directly observed the faint infrared light emitted by these giant planets themselves. By focusing on a narrow band of infrared wavelengths—between 3 and 5 micrometers—the team captured specific signals from carbon dioxide and other molecules, offering a direct and detailed look at the atmospheric makeup.

“The coronagraphs were essential,” said Rémi Soummer, who leads the Optics Laboratory at the Space Telescope Science Institute. “They block out the bright starlight and let us peer into regions we’ve never been able to study before. We’ve waited 10 years to confirm Webb could do this. Now we know.”

Beyond HR 8799: Other Worlds, More Discoveries

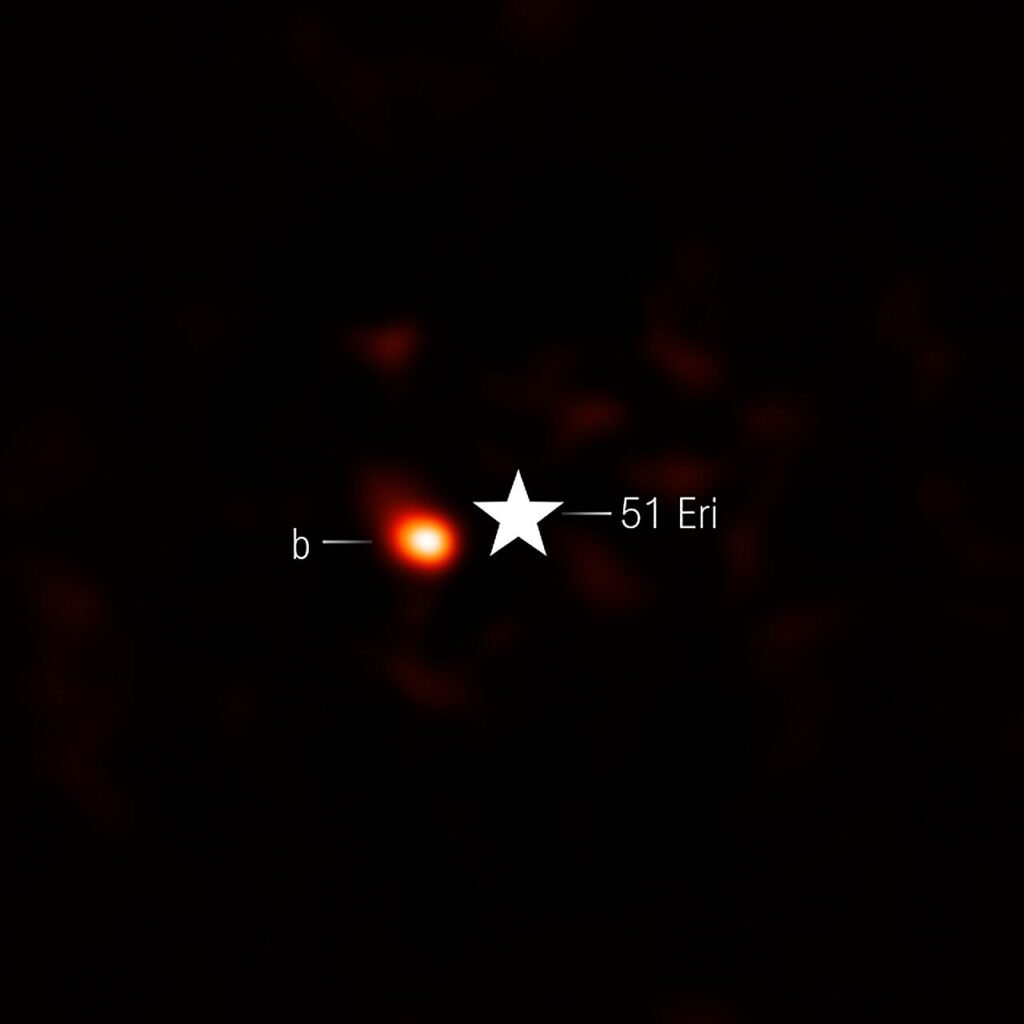

The Webb team didn’t stop with HR 8799. They also observed 51 Eridani b, a young giant planet orbiting a star about 96 light-years away. Like the HR 8799 planets, 51 Eridani b showed clear signs of carbon dioxide—specifically at 4.1 micrometers—revealing the extraordinary sensitivity Webb brings to these types of studies.

But perhaps the most thrilling moment came when Webb detected HR 8799 e—the system’s innermost planet—at a wavelength of 4.6 micrometers. This was the first time scientists had directly imaged this planet at this wavelength, opening up entirely new windows into its atmosphere and composition.

“The fact that we can now directly observe these inner planets is a game-changer,” said Laurent Pueyo, co-lead on the project from the Space Telescope Science Institute. “It’s not just about seeing them; it’s about understanding them.”

Implications for the Search for Life

So why does detecting carbon dioxide matter so much? On Earth, carbon dioxide plays a key role in regulating climate and supporting life through processes like photosynthesis. While the CO2 detected on these giant planets doesn’t indicate life, it helps scientists understand the chemical pathways that could lead to life-friendly environments on smaller, rocky planets.

“These giant planets act like cosmic wrecking balls,” Balmer explained. “They can shape the orbits of smaller planets, deliver water and organic molecules, or even protect inner planets from asteroid impacts. Understanding how these giants form and evolve is critical to figuring out whether Earth-like worlds could survive and thrive in similar systems.”

What’s Next? More Webb, More Worlds

This latest discovery is just the beginning. The team plans to use JWST’s coronagraphs and spectrometers to observe more exoplanets directly. By comparing different planetary systems, they hope to determine how common the core accretion model is for gas giants and whether certain chemical signatures consistently show up in planets formed this way.

“How common is this bottom-up approach to forming planets? We’re not sure yet,” Pueyo said. “But with more Webb observations, we’re going to find out.”

And as Webb continues to deliver stunning data, astronomers may soon have enough information to draw broader conclusions about how planetary systems emerge and evolve—potentially shedding light on the conditions that made life on Earth possible.

“We’re on the verge of understanding not just individual planets, but the architecture of entire solar systems,” Soummer said. “And that could tell us where to look for life next.”

A New Era of Discovery

In just over a year of operation, JWST has revolutionized our understanding of exoplanets. Its ability to directly detect molecules like carbon dioxide in the atmospheres of distant worlds is transforming how we explore our cosmic neighborhood.

“For decades, we’ve dreamed of taking detailed pictures of other solar systems,” Balmer said. “Now we’re doing it.”

And this is only the beginning. With the James Webb Space Telescope in operation, the universe is no longer just a distant dream. It’s becoming a place we can study, explore, and perhaps one day visit.

Reference: JWST-TST High Contrast: Living on the Wedge, or, NIRCam Bar Coronagraphy Reveals CO2 in the HR 8799 and 51 Eri Exoplanets’ Atmospheres, The Astrophysical Journal (2025). DOI: 10.3847/1538-3881/adb1c6

Think this is important? Spread the knowledge! Share now.