The burial practices of early human ancestors have long fascinated archaeologists and anthropologists, offering crucial insights into the cultural and cognitive behaviors of Homo sapiens and Neanderthals. A recent study published in L’Anthropologie, led by Professor Ella Been of Ono Academic College and Dr. Omry Barzilai from the University of Haifa, delves into the Middle Paleolithic (MP) burial practices in the Levant, a region central to human evolution. This study, which examines the burial practices of both Homo sapiens and Neanderthals, sheds new light on the similarities and differences between the two species, providing a fresh perspective on how they treated their dead and what this reveals about their culture, social structures, and cognitive abilities.

The Context: Homo sapiens and Neanderthals in the Levant

The Levant, a region encompassing modern-day countries like Israel, Jordan, Syria, Lebanon, and Palestine, is a key area in the study of human evolution. The Middle Paleolithic, a period ranging from about 300,000 to 30,000 years ago, was marked by the co-existence of two hominin species: Homo sapiens and Neanderthals. While Homo sapiens arrived in the region between 170,000 and 90,000 years ago, re-entering around 55,000 years ago from Africa, Neanderthals had already been present in the Levant for tens of thousands of years, having migrated from Europe roughly 120,000 to 55,000 years ago.

During this period, both species engaged in a practice that would later become central to human culture: burial of the dead. The sudden emergence of burial practices in the Levant around this time, and the stark differences in how Homo sapiens and Neanderthals buried their dead, have long been a subject of intrigue. The practice of burying the dead is widely considered to be a cultural milestone, marking the development of symbolic thought, ritual, and social organization.

A New Lens on Burial Practices

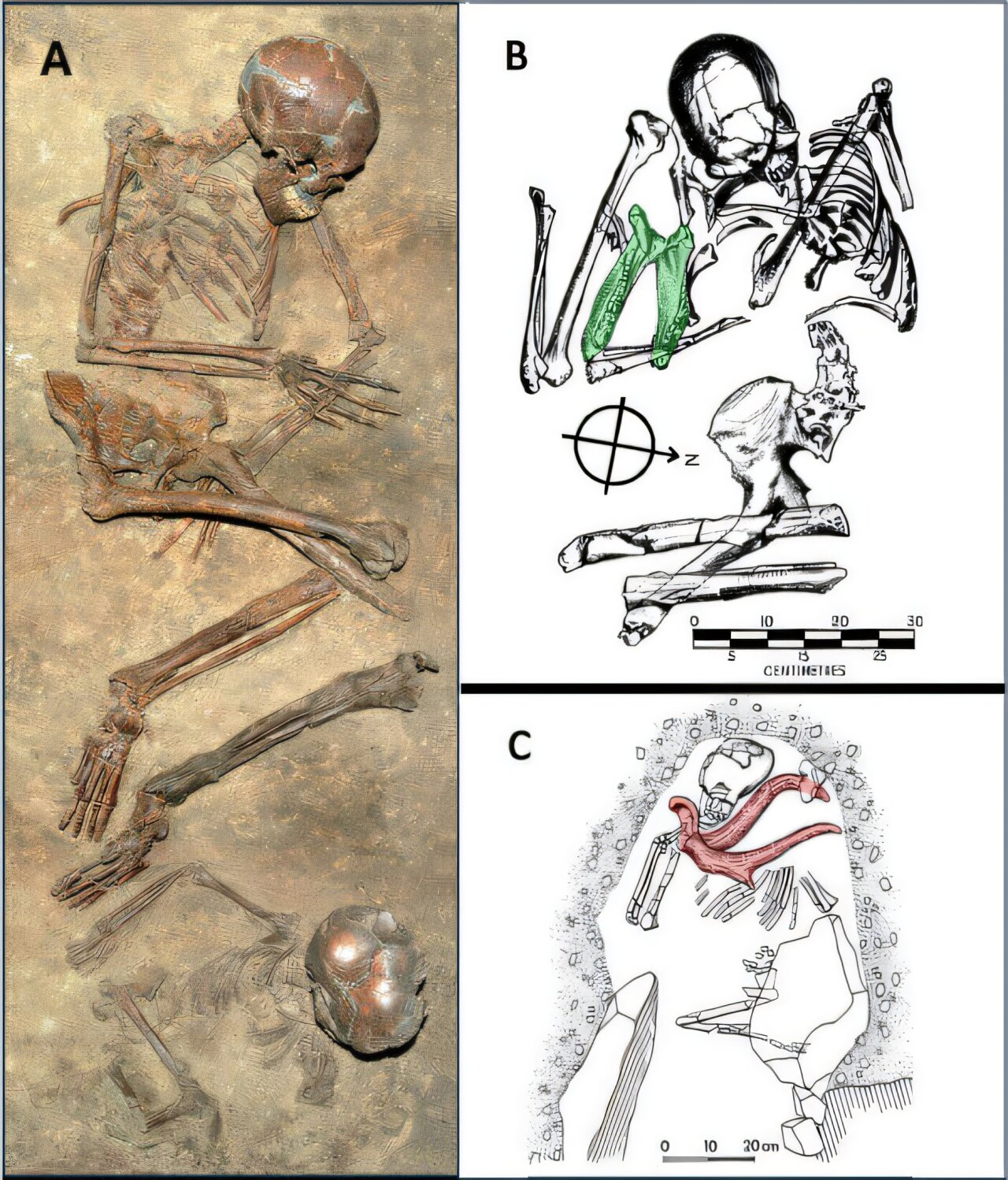

In their study, Professor Been and Dr. Barzilai analyzed 17 Neanderthal burials and 15 Homo sapiens burials from various archaeological sites in the Levant, including famous sites like Teshik Tash, Shanidar, Dederiyeh, Amud, Tabun, and Kebara caves for the Neanderthals, and Skhul Cave and Qafzeh Cave for the Homo sapiens. Their research revealed striking similarities and differences between the burial practices of the two species, offering new insights into their cultural behaviors.

According to the researchers, both Homo sapiens and Neanderthals buried their dead, regardless of age or sex, suggesting a shared practice of honoring the deceased. However, when it came to the specifics of burial practices, the two species exhibited notable differences. Neanderthal burials, for instance, were more diverse in terms of body posture, with individuals sometimes buried in a flexed (fetal-like) position, while others were placed in extended (straight) or semi-flexed positions. These burials often involved varying burial orientations, with some individuals buried lying on their backs, while others were placed on their left or right sides.

In contrast, Homo sapiens burials tended to be more uniform, with most individuals buried in a flexed posture. Additionally, Homo sapiens were more likely to bury their dead in cave entrances or rock shelters, whereas Neanderthals typically placed their dead deep inside caves (with the exception of one open-air burial at EQ3, a Neanderthal site in Israel). This suggests that Neanderthals may have had a more intimate relationship with cave environments, using them not only as living spaces but also as ritualistic burial sites.

Grave Goods and Symbolism

Another fascinating aspect of the study is the analysis of grave goods, objects placed alongside the deceased. Both Homo sapiens and Neanderthals occasionally included animal remains in their burials. These remains—ranging from goat horns to deer antlers, and even mandibles and maxillae—might have served symbolic or ritualistic purposes, reflecting an early form of belief in the afterlife or a connection between the living and the natural world.

However, there were significant differences in the types of grave goods included in the burials of each species. While Neanderthals occasionally included animal remains, they were also known to place rocks in their graves. In some cases, large rocks were positioned around the body, possibly to mark the burial site or serve as a symbolic boundary between the living and the dead. Some Neanderthal burials even included modified limestone pieces placed under the head as a form of headrest, further indicating a degree of care and ritual involved in burial practices.

On the other hand, Homo sapiens burials in the Levant were more likely to feature ocher and marine shells, items that were completely absent from Neanderthal burials. Ocher, a pigment often associated with ritual and symbolic practices, suggests that Homo sapiens may have engaged in more complex rituals surrounding death, potentially reflecting a belief in an afterlife or spiritual practices. The presence of marine shells, often considered exotic items, further indicates the possibility of long-distance trade or a shared symbolic language among different groups of Homo sapiens in the region.

A Sudden Surge in Burials

What makes this period in the Levant particularly intriguing is the sudden surge in burials around 100,000 years ago. Prior to this time, there is no evidence of systematic burial practices among either Homo sapiens or Neanderthals. The appearance of burial practices during the Middle Paleolithic in the Levant is an unprecedented development in human history, and its occurrence in such a condensed region is striking. For comparison, in Africa and Europe, burials were far more sparse, with only a handful of examples from the same period.

The researchers suggest that the rapid increase in burials in the Levant could be linked to an increase in population density. As the climate of the region became more humid, the Saharo-Arabian desert transformed into a more fertile landscape, attracting Homo sapiens from East Africa. At the same time, the melting of glaciers in the Taurus and Balkan mountains opened pathways for Neanderthals to migrate southward into the Levant. The convergence of these two populations likely led to increased demographic pressure, which may have contributed to the proliferation of burial practices.

Interestingly, this burst of burials came to an abrupt halt around 50,000 years ago, just before the extinction of Neanderthals. According to Professor Been, this cessation of burials is particularly puzzling, as there was a marked decline in burial activity following the disappearance of Neanderthals. This gap in burial practices lasted until the Late Paleolithic, around 15,000 years ago, when the semi-sedentary Natufian culture revived the tradition of burial.

The Evolution of Cultural Practices: Why Did Burials Emerge?

The study by Professor Been and Dr. Barzilai not only illuminates the burial practices of Homo sapiens and Neanderthals but also raises important questions about the cultural evolution of these species. Why, at this specific point in time, did both species begin to bury their dead in such a deliberate manner? What cultural, social, or cognitive factors prompted this shift?

The researchers hypothesize that demographic pressure could have played a role, particularly in the context of increased population density in the Levant. However, they also caution against oversimplifying the emergence of burial practices as solely a response to population growth. Burials are deeply symbolic and carry profound cultural meaning, suggesting that other factors—such as social cohesion, ritualistic beliefs, or even the development of language and cognitive abilities—may have also contributed to the innovation of burial practices.

Continuing the Research: Insights into Neanderthal Culture

Professor Been’s research into Neanderthal burial practices is ongoing, with her current work focusing on the burial of a Neanderthal infant from the Amud Cave in Israel. By studying the specifics of this particular burial, Professor Been hopes to gain further insights into Neanderthal cultural practices, especially in relation to the treatment of the dead. This continued research promises to deepen our understanding of the similarities and differences between Homo sapiens and Neanderthals, shedding light on the complex and multifaceted nature of their cultural evolution.

Conclusion: What Burials Reveal About Early Humans

The study by Professor Been and Dr. Barzilai offers a fascinating glimpse into the burial practices of Homo sapiens and Neanderthals in the Levant during the Middle Paleolithic. By examining the similarities and differences between these two species, the researchers provide valuable insights into their cognitive abilities, social structures, and cultural beliefs.

The emergence of burial practices in the Levant represents a critical turning point in human evolution, marking the development of symbolic thought and complex rituals. While the exact reasons behind the sudden appearance of burials remain unclear, it is evident that these practices were not only a response to demographic pressures but also a reflection of the cultural and social dynamics of early human populations.

As research in this field continues, the study of ancient burials will undoubtedly reveal even more about the lives and beliefs of our distant ancestors, helping to unravel the mysteries of human evolution.

Reference: Ella Been et al, Neandertal burial practices in Western Asia: How different are they from those of the early Homo sapiens?, L’Anthropologie (2024). DOI: 10.1016/j.anthro.2024.103281