Chronic pain remains one of the most complex and elusive health issues, afflicting millions worldwide. It is often difficult to treat, with many existing therapies providing only limited relief. However, a groundbreaking study conducted by researchers at the University of California, San Francisco, has uncovered a fascinating new mechanism that could change the way we think about chronic pain treatment. Their research reveals a surprising connection between immune cells, female hormones, and the body’s ability to manage pain. This discovery not only offers insights into why some painkillers work better for women than for men but could also pave the way for novel, more effective treatments for chronic pain, especially in postmenopausal women.

Immune Cells, Female Hormones, and Pain Relief: The Unexpected Connection

The study, which appears in the journal Science, focuses on the role of T-regulatory immune cells (T-regs), which have long been associated with immune function. These cells are crucial for maintaining the body’s immune system, helping to prevent autoimmune diseases by suppressing excessive immune responses. However, the researchers at UCSF have revealed that these cells play an entirely different role in pain management, particularly in females.

Elora Midavaine, Ph.D., a postdoctoral fellow and the first author of the study, explains the significance of the findings: “The fact that there’s a sex-dependent influence on these cells—driven by estrogen and progesterone—and that it’s not related at all to any immune function is very unusual.” What Midavaine is referring to is a surprising discovery: Female hormones like estrogen and progesterone can suppress pain by triggering T-regs to produce pain-relieving opioids, specifically a substance known as enkephalin. This process happens near the spinal cord, effectively preventing pain signals from reaching the brain. This novel mechanism could revolutionize how we approach chronic pain treatment.

The Unlikely Role of Meninges in Pain Perception

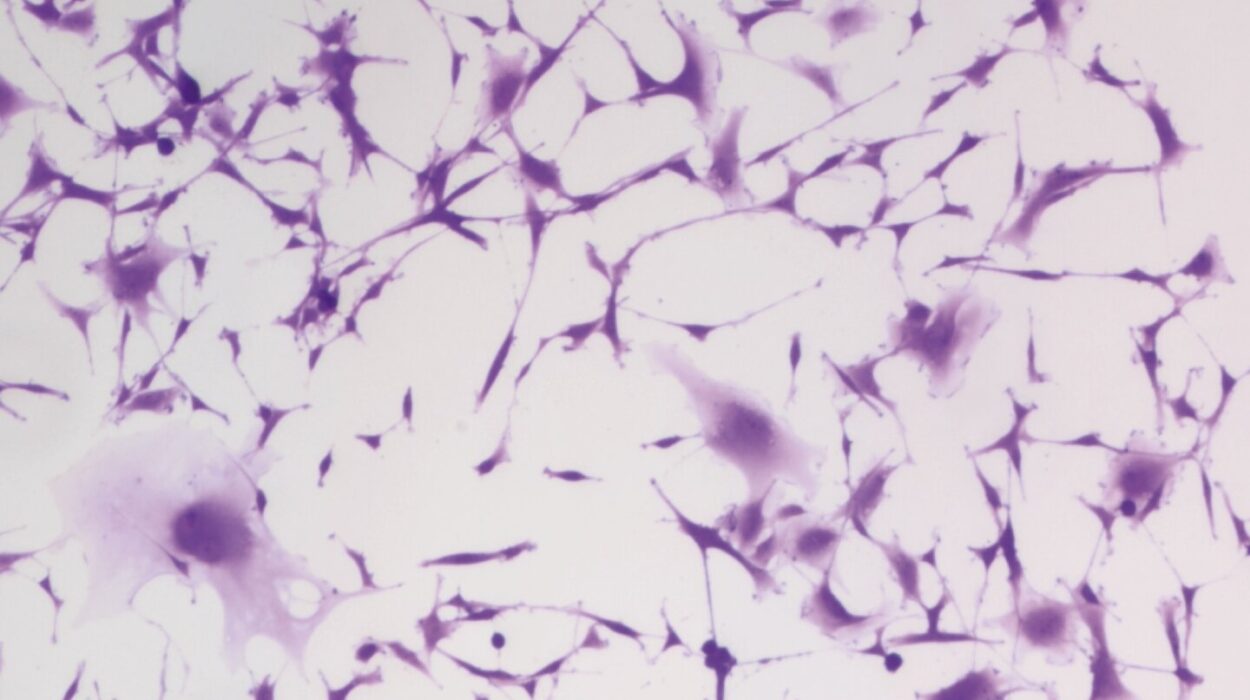

The researchers focused on T-regs in a particular area of the body— the meninges, which are the protective membranes surrounding the brain and spinal cord. Until now, scientists had believed that the meninges’ primary function was simply to provide a physical barrier, shielding the central nervous system from harm. However, the UCSF team discovered that these tissues play a far more active role in the body’s communication system, particularly when it comes to pain.

Sakeen Kashem, M.D., Ph.D., assistant professor of dermatology and co-leader of the study, explains: “What we are showing now is that the immune system actually uses the meninges to communicate with distant neurons that detect sensation on the skin.” This new understanding challenges previous assumptions about the meninges and highlights how the immune system interacts with sensory neurons to detect and respond to potential pain stimuli.

How It Works: The New Pain Pathway

The process begins when a sensory neuron, often located near the skin, detects something that could potentially cause pain, such as a burn or injury. This neuron then sends a signal to the spinal cord, which transmits the information to the brain. However, the UCSF researchers discovered that the meninges, which surround the spinal cord, harbor an abundance of T-regs. These immune cells seem to play a role in modulating the pain signal before it reaches the brain.

To understand the function of these T-regs, the researchers performed experiments in which they “knocked out” these cells in mice using a toxin. What they found was striking: In female mice, the absence of T-regs resulted in increased sensitivity to pain, while male mice did not show the same response. This sex-specific difference was both surprising and puzzling. It suggested that female mice rely more on T-regs to manage pain than male mice do.

Kashem was initially skeptical of the results. “It was both fascinating and puzzling,” he recalls. “But after further investigation, we began to realize that this was a significant and previously unknown mechanism in pain management.”

Estrogen, Progesterone, and Pain Relief

The researchers’ further experiments revealed an even more unexpected connection: T-regs in female mice were responding to the presence of estrogen and progesterone by producing enkephalin, an opioid-like substance known to suppress pain. Enkephalin works by binding to opioid receptors in the brain and spinal cord, preventing pain signals from reaching the brain. This discovery underscores the critical role that female hormones play in pain management and suggests that women’s bodies have a distinct, hormone-driven pathway for controlling pain that men lack.

“This was a game-changing finding,” says Allan Basbaum, Ph.D., a co-leader of the study and a renowned expert in pain research. “The fact that these hormones are triggering T-regs to produce natural painkillers like enkephalin could explain why some painkillers, like those used for migraines, work better for women than for men.”

A New Approach for Treating Chronic Pain

The implications of this discovery are profound, especially for women who suffer from chronic pain. Women, particularly those who are postmenopausal, often experience pain differently than men due to hormonal changes. After menopause, women’s bodies no longer produce estrogen and progesterone, which may explain why many postmenopausal women suffer from chronic pain conditions, including joint pain, migraines, and fibromyalgia.

The study suggests that the absence of estrogen and progesterone after menopause could impair the ability of T-regs to manage pain, leaving women more vulnerable to chronic pain. By better understanding this mechanism, researchers hope to develop treatments that can either mimic the effects of these hormones or restore T-reg function in postmenopausal women.

In the short term, the findings could help doctors make more informed decisions about pain treatment. For example, physicians might consider prescribing pain medications that target the same pathways activated by estrogen and progesterone, particularly for women suffering from conditions like migraines or fibromyalgia. These medications could be more effective for women, as they would work with the body’s natural pain control mechanisms.

Engineering T-regs for Constant Pain Relief

Looking to the future, the researchers are exploring the possibility of engineering T-regs to produce enkephalin on a constant basis, regardless of a person’s hormonal status. If this approach proves successful, it could provide a groundbreaking treatment for chronic pain that works for both men and women. Engineering T-regs to produce pain-relieving opioids could potentially offer a new class of painkillers that are more natural and less addictive than traditional pharmaceuticals.

“If that approach is successful, it could really change the lives of the nearly 20% of Americans who experience chronic pain that is not adequately treated,” says Basbaum. Chronic pain remains a significant challenge in modern medicine, and this research holds the promise of offering more targeted and effective therapies in the near future.

Conclusion: A New Frontier in Chronic Pain Research

The discovery of this new pain pathway involving immune cells and female hormones is a monumental step forward in the field of pain research. It offers fresh insights into the biological mechanisms that govern pain perception and provides a potential avenue for developing more effective treatments. By uncovering the intricate relationship between T-regs, hormones, and pain management, the researchers at UCSF have opened the door to a new era in pain therapy—one that takes into account sex differences, hormonal influences, and the body’s own natural pain-relief mechanisms.

As scientists continue to explore this novel pathway, we may be on the cusp of a paradigm shift in how we understand and treat chronic pain. In the future, pain management may become more personalized, offering therapies tailored to an individual’s unique biological makeup, ultimately improving the quality of life for millions of people around the world.

Reference: Élora Midavaine et al, Meningeal regulatory T cells inhibit nociception in female mice, Science (2025). DOI: 10.1126/science.adq6531. www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.adq6531