The recent discoveries at the Prado Vargas Cave in Burgos, Spain, led by the Universidad de Burgos, have provided intriguing new evidence suggesting that Neanderthals may have engaged in collecting activities that go beyond mere survival. The unearthing of 15 marine fossils from the Upper Cretaceous period has prompted a reevaluation of the cognitive and cultural complexities of Neanderthal behavior. These fossils, which show no signs of practical use, may have been gathered not for food or tools, but for reasons that reflect an appreciation for aesthetics, symbolism, or even social practices. This finding pushes the boundaries of how we view Neanderthal culture, indicating that these early hominins may have engaged in practices much more sophisticated than previously thought, possibly laying the groundwork for behaviors we often associate with modern humans.

The Fascinating World of Collecting: A Human Trait or a Neanderthal Activity?

Collecting objects for non-practical reasons—whether for aesthetic pleasure, symbolic meaning, or social purposes—is often seen as a distinctly human trait. Today, collecting is a common pastime enjoyed by people all over the world. From stamps and coins to action figures, trading cards, and even rare Pokémon, humans have long had a penchant for amassing objects that hold personal or cultural significance. This behavior extends far back into history. King Ashurbanipal of Assyria, for example, amassed an impressive collection of clay tablets in the 7th century BCE, marking the first known version of a book collection.

However, the desire to collect objects may not be so recent after all. In fact, the earliest evidence of this behavior dates back much further than human civilization itself. For instance, a reddish jasper stone resembling a human face was discovered in the Makapansgat Valley in South Africa. It is believed to have been collected by Australopithecus africanus, an early human ancestor, who placed it in a cave, possibly for safekeeping or as a form of curiosity. Likewise, Homo erectus, an even earlier species, has been linked to the collection of an engraved mussel shell found on the island of Java.

Neanderthals, too, have left behind evidence of collecting behaviors, albeit in ways that are both surprising and profound. Fossils, seashells, quartz crystals, and even antlered skulls have been unearthed in Neanderthal settlements, some coming from distant locations. These objects do not appear to have had any immediate functional use, but their presence suggests that Neanderthals valued them for reasons beyond practicality. The discovery at the Prado Vargas Cave furthers this argument, as it reveals a collection of marine fossils that likely held no utilitarian value.

Neanderthal Collecting Practices: Evidence from the Prado Vargas Cave

The study published in the journal Quaternary, titled “Were Neanderthals the First Collectors? First Evidence Recovered in Level 4 of the Prado Vargas Cave, Cornejo, Burgos and Spain,” offers a fascinating glimpse into the collecting practices of Neanderthals. This research, which focused on a stratigraphic layer of the cave known as Mousterian Level N4, dates back to approximately 39.8 to 54.6 thousand years ago. During this period, Neanderthals likely inhabited the cave, using it as a stable camp for toolmaking, hunting, and possibly engaging in symbolic behaviors.

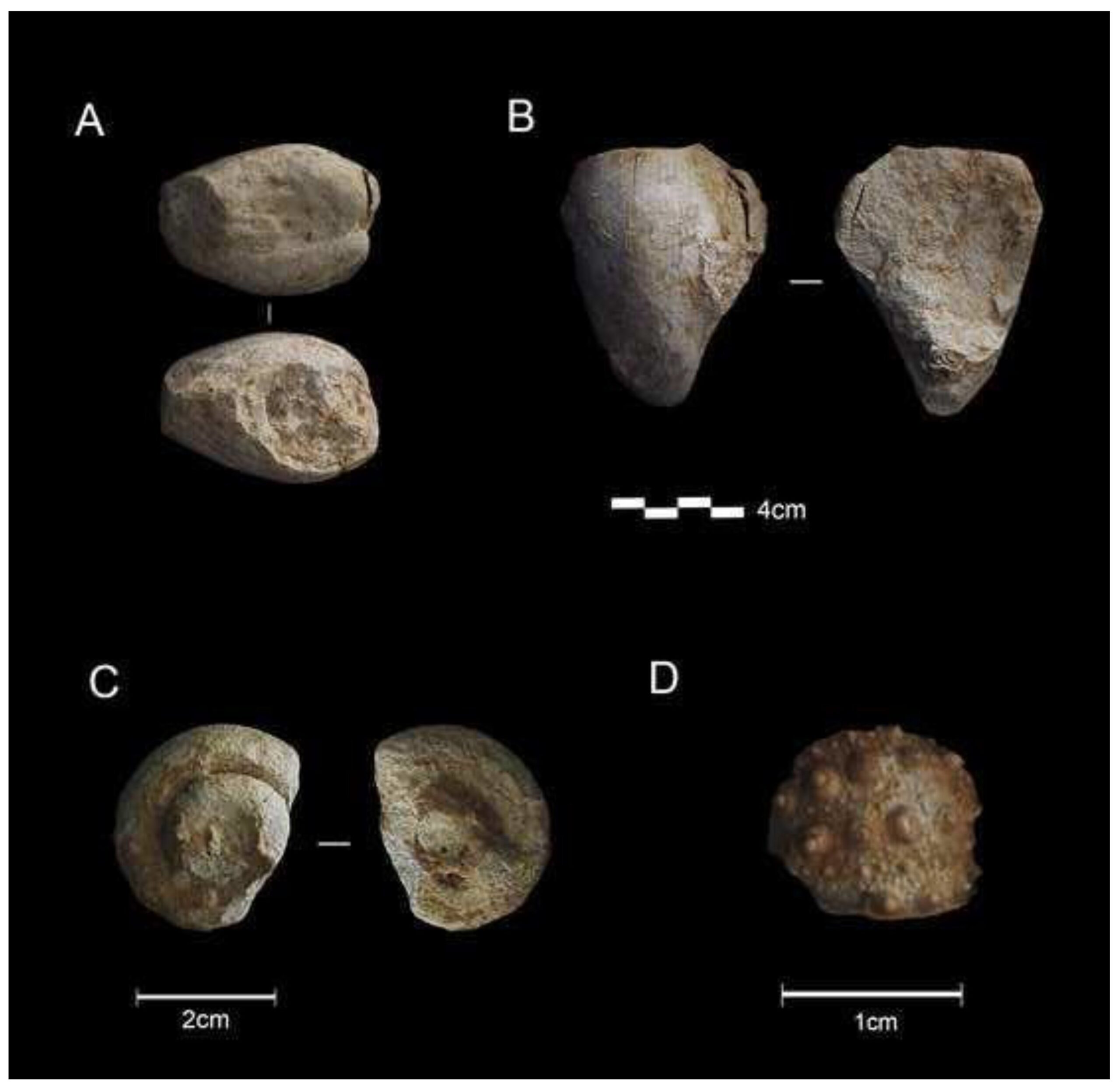

The discovery of 15 marine fossils in the cave provides new evidence that Neanderthals engaged in the gathering of objects that did not serve an immediate practical function. These fossils, which include species such as Tylostoma, Granocardium productum, and Pholadomya gigantea, are small, averaging less than 2 inches (5 cm) in size. Interestingly, these fossils show no signs of modification, indicating that they were not used as tools or ornaments. Instead, their presence in the cave suggests that Neanderthals might have collected them for reasons related to aesthetic enjoyment, symbolic meaning, or social behaviors such as gift-giving or exchange.

What makes this discovery particularly compelling is the origin of these fossils. They were not native to the cave’s immediate geological context but instead were likely gathered from Upper Cretaceous formations located more than 30 kilometers away. The distance from the source raises the question: Why would Neanderthals go through the effort of collecting these fossils from such a far distance if they had no practical use? The answer, according to the study, may lie in the cultural significance of the objects themselves.

Motivations for Collecting: Aesthetic, Symbolic, and Social Significance

The presence of non-utilitarian objects in Neanderthal settlements is not entirely new. Previous archaeological findings have suggested that Neanderthals engaged in symbolic practices, such as the use of pigments, the creation of ornaments, and even the painting of cave walls. The act of collecting marine fossils could have been another form of symbolic behavior, reflecting an appreciation for the aesthetic qualities of these objects or their potential symbolic meaning. Fossils, with their intricate shapes and the stories they tell of ancient life, might have captivated the Neanderthals’ imagination, just as they continue to intrigue scientists and fossil enthusiasts today.

Moreover, the study speculates that these fossils could have had social significance. In human societies, the act of collecting objects often serves as a means of social bonding, whether through the exchange of gifts or the sharing of rare and prized items. If Neanderthals were indeed collecting these fossils for social purposes, they may have been involved in early forms of social interaction that involved the exchange of meaningful objects.

The cognitive abilities required for such collecting behaviors are also noteworthy. The act of selecting objects for their aesthetic or symbolic value suggests that the Neanderthals possessed the ability to engage in abstract thinking. This aligns with previous evidence that Neanderthals had complex cognitive capacities. For instance, they demonstrated an understanding of burial practices, used pigments for body decoration, and crafted ornaments from materials such as bone, ivory, and shells. Collecting objects for non-practical reasons adds another layer of sophistication to their cognitive abilities and suggests that Neanderthals may have been more culturally complex than we once thought.

Could Children Have Been the First Collectors?

Another intriguing aspect of this study is the possibility that the fossils were collected by Neanderthal children. The researchers note that evidence of children living in the settlement exists, and it is entirely plausible that they were the ones who gathered the fossils. This notion brings to mind a behavior often seen in modern-day children—collecting and playing with objects simply because they are interesting or rare. Children frequently collect things like rocks, seashells, and even sticks, often motivated by curiosity and the thrill of discovery.

Could these marine fossils have been a form of early play? Perhaps the Neanderthal children used them in games, much like modern children use marbles, stones, or dice. Gaming and toy artifacts are often overlooked in archaeological studies, as they are typically not associated with utility. However, considering the playful nature of modern childhood, it is worth entertaining the possibility that Neanderthal children collected these fossils for similar reasons. They might have used them in a primitive game or simply enjoyed the act of gathering interesting items, creating their own form of social interaction and entertainment.

The First Collectors? The Enduring Mystery of Neanderthal Curiosity

In conclusion, the discovery of marine fossils at the Prado Vargas Cave presents compelling evidence that Neanderthals may have been the first known collectors, engaged in behaviors that were previously thought to be uniquely human. The act of gathering objects for non-utilitarian reasons challenges our understanding of Neanderthal culture and cognition. These early hominins may have appreciated the aesthetic value of the fossils, imbued them with symbolic meaning, or used them in social practices that reinforced group cohesion. The possibility that Neanderthal children were involved in this collecting activity adds another fascinating layer to this discovery, suggesting that play and curiosity were integral to their lives.

The study of Neanderthal collecting behaviors is still in its early stages, and much remains to be learned. However, the Prado Vargas Cave findings offer a glimpse into the complex and multifaceted nature of Neanderthal society. The idea that these ancient humans possessed a sense of wonder and curiosity, and that they may have engaged in activities as seemingly innocuous as collecting fossils, brings them closer to us in ways we had never imagined. Just as modern humans collect objects for joy, nostalgia, and social reasons, so too might have our Neanderthal ancestors, laying the foundation for the human propensity to collect, create, and connect.

Reference: Marta Navazo Ruiz et al, Were Neanderthals the First Collectors? First Evidence Recovered in Level 4 of the Prado Vargas Cave, Cornejo, Burgos and Spain, Quaternary (2024). DOI: 10.3390/quat7040049