For decades, Barnard’s Star has been the subject of whispered hope and quiet obsession among astronomers. It’s a faint red dwarf, sitting just six light-years away from Earth—a stone’s throw in cosmic terms. As the second-nearest star system to our own, its proximity has long made it an alluring target in the hunt for alien worlds. Now, a major breakthrough has brought that dream into sharper focus: astronomers have unveiled compelling evidence of not one, but four small, rocky planets orbiting Barnard’s Star.

The discovery, published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, marks a significant advance in the search for small, Earth-like planets circling nearby stars. And while these newly revealed worlds may be too hot to support life as we know it, their existence pushes the boundaries of how—and where—we find planets beyond our solar system.

“It’s a really exciting find,” said Ritvik Basant, a Ph.D. student at the University of Chicago and lead author of the study. “Barnard’s Star is our cosmic neighbor, and yet we’ve only just begun to understand what’s orbiting it. This discovery signals a breakthrough, made possible by the precision of new instruments that surpass anything we’ve used before.”

A New Era of Precision and Discovery

Barnard’s Star has long tantalized astronomers. First noted by E. E. Barnard in 1916 for its rapid motion across the sky, this cool, dim M-dwarf star has been a focal point for planet hunters. Unlike Proxima Centauri—our actual closest stellar neighbor—Barnard’s Star is a solitary sun. That makes it an ideal candidate for studying planetary systems that resemble our own, free from the gravitational chaos of multiple stars.

Until now, most searches around Barnard’s Star had turned up either empty-handed or with results later debunked. That’s why this discovery is such a landmark moment. The four newfound planets are tiny, each between 20% and 30% of Earth’s mass. They zip around their star at dizzying speeds, completing full orbits in mere days.

This is no quiet procession of planets. These small worlds are locked in scorching proximity to Barnard’s Star, likely too close and too hot for habitability. But what makes them particularly exciting is their size. Most exoplanets found around M-dwarf stars have tended to be much larger, often gas giants or hefty rocky worlds known as super-Earths. These new planets are some of the smallest exoplanets ever confirmed around a nearby star.

The Tools Behind the Triumph

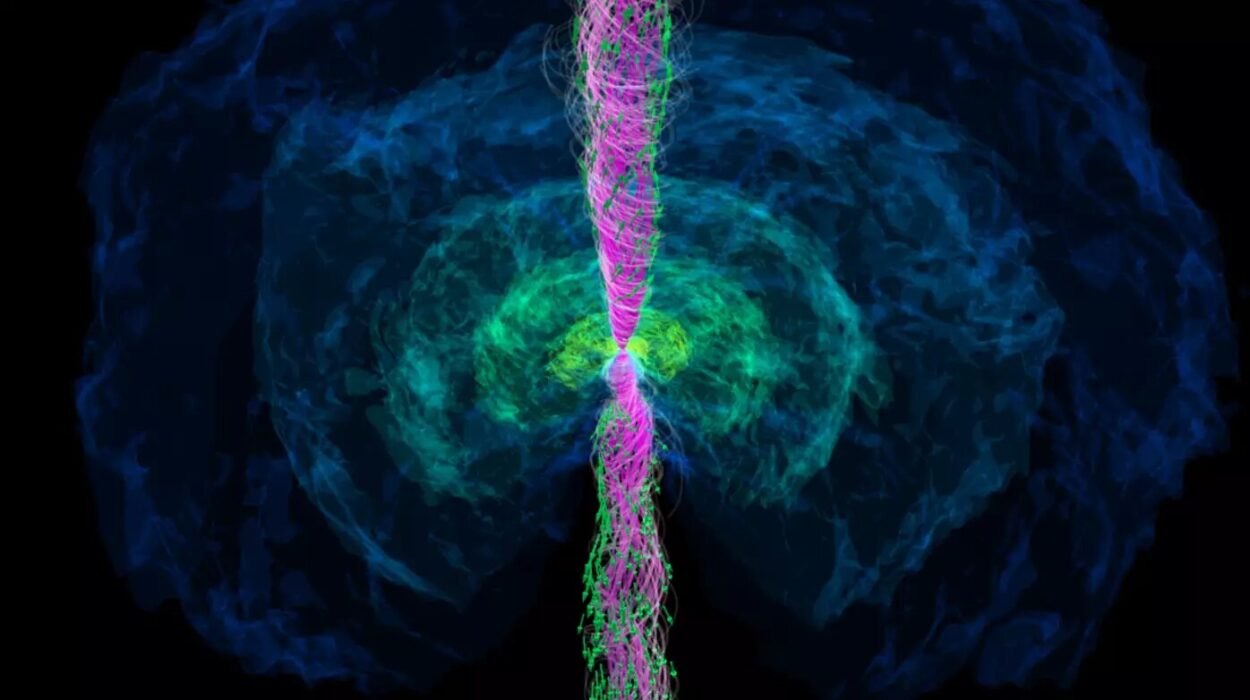

So how did scientists finally crack the case? Enter MAROON-X, a cutting-edge instrument mounted on the Gemini North Telescope, perched atop Mauna Kea in Hawaii. MAROON-X was custom-built by a team led by University of Chicago professor Jacob Bean to detect small, Earth-sized planets around nearby stars. It works by measuring a star’s subtle back-and-forth wobble caused by the gravitational tug of orbiting planets.

“Think of it like watching a flag flapping in the wind,” Basant explains. “You can’t see the wind itself, but you can see its effect on the flag. In the same way, we can’t directly see these tiny planets next to a bright star, but we can detect the way they pull on their star.”

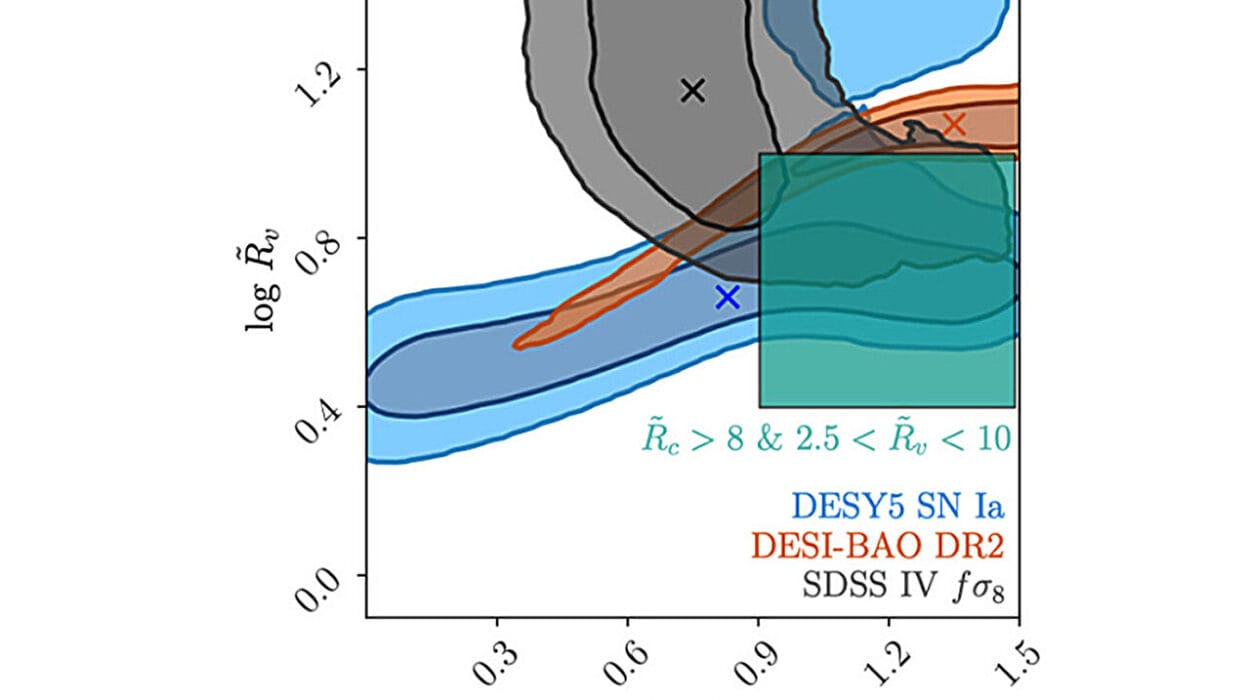

Over three years, the team gathered data on 112 nights, meticulously monitoring Barnard’s Star for shifts in its light. The data revealed the telltale signs of three distinct planets. Then, by combining their data with independent observations from the ESPRESSO instrument at the Very Large Telescope in Chile—a project that had previously suggested the presence of one planet—they realized there was strong evidence for a fourth planet.

“This cross-confirmation is what makes the discovery so compelling,” said Basant. “Two different teams, using two completely separate instruments on opposite sides of the world, detected the same signals. That rules out a lot of other possibilities. These aren’t phantom planets—they’re real.”

The Planets of Barnard’s Star: Hot, Small, and Rocky

While these planets are too close to their star to harbor liquid water, they are likely rocky in composition, not unlike Mercury or Mars in our own solar system. Confirming that, however, is a bit trickier. Because of the angle from which we observe Barnard’s Star, we can’t see these planets pass directly in front of it—a method known as the transit technique that can reveal a planet’s size and, sometimes, hints about its atmosphere.

But by comparing them to other small exoplanets found around M-dwarf stars, scientists can make educated guesses about their makeup. And every new discovery adds data points that help refine those models.

Perhaps more importantly, the researchers were able to rule out the existence of any other planets in the star’s so-called “habitable zone”—the not-too-hot, not-too-cold region where liquid water could exist. At least for now, there’s no Earth-like twin orbiting at just the right distance from Barnard’s Star. But that doesn’t make this find any less groundbreaking.

A Cosmic Quest, Decades in the Making

For planet hunters, Barnard’s Star has been something of a “great white whale.” Over the last hundred years, there have been repeated claims of planets in its orbit—claims that ultimately failed under closer scrutiny.

The new findings are different. Independently confirmed by multiple observatories and teams, these detections stand on solid ground.

“We observed at different times of night, on different days,” Basant noted. “They’re in Chile; we’re in Hawaii. Our teams didn’t coordinate at all. That gives us a lot of assurance that these signals are real.”

Why This Matters: Small Worlds, Big Questions

Finding these four planets around Barnard’s Star isn’t just a triumph of technique—it’s a glimpse into a new frontier of discovery. Until recently, the majority of exoplanets we’ve detected have been larger than Earth, often by a significant margin. Smaller planets have been far more elusive, in part because they’re harder to detect with older instruments.

But smaller planets could hold the greatest variety—and perhaps, the greatest promise. They may be more likely to have rocky surfaces, diverse atmospheres, and environments that could, in the right circumstances, support life.

“This discovery pushes the boundaries of what we can do,” Bean said. “We’re now able to find planets that are not only smaller but also orbiting stars very close to us. That means we can follow up with other studies—maybe even direct imaging one day.”

And every new planet found in our neighborhood tells us something about our place in the cosmos.

“We’re starting to map out the planetary real estate around nearby stars,” Basant said. “And we’re finding that the universe is richer and more diverse than we ever imagined.”

A Thrill of Discovery That Never Gets Old

For the team behind the discovery, the thrill of unveiling these worlds was as personal as it was scientific.

“We worked on this data really intensely at the end of December,” Bean recalled. “I was thinking about it all the time. It’s that feeling—suddenly we know something that no one else in the world knows. It’s a secret about the universe that we get to share.”

“A lot of science is incremental. It can feel like you’re making small steps,” he continued. “But sometimes, you get to be part of something big, something that might stand for centuries. That’s an incredible feeling.”

What’s Next for Barnard’s Star—and Beyond?

The discovery of these four planets is just the beginning. Now that scientists have confirmed their presence, follow-up studies will try to learn more. Can we detect any signs of atmospheres? Can we refine our measurements of their masses and compositions? Could future telescopes—like the upcoming James Webb Space Telescope’s successors—take direct images of these planets or analyze their atmospheres?

Meanwhile, MAROON-X and ESPRESSO will continue their hunt, peering at other nearby stars in search of more small planets. Each discovery helps build a clearer picture of how planetary systems form and evolve—offering clues about how common Earth-like worlds may be.

“This is opening the door to finding more of these small, rocky planets,” Basant said. “It’s an exciting time to be an astronomer.”

For now, Barnard’s Star shines a little brighter in humanity’s collective imagination. Not just a lonely red dwarf, but a host to a quartet of small worlds, orbiting at breakneck speed in its fiery embrace. A neighbor with secrets, and a new chapter in the unfolding story of our search for other worlds.

Reference: Ritvik Basant et al, Four Sub-Earth Planets Orbiting Barnard’s Star from MAROON-X and ESPRESSO, The Astrophysical Journal Letters (2025). DOI: 10.3847/2041-8213/adb8d5