A groundbreaking study from the University of Bergen in Norway has provided new insights into the long-underestimated role of women in medieval manuscript production, revealing that at least 1.1% of medieval manuscripts, produced between 800 and 1626 CE, were copied by female scribes. With this figure, the researchers estimate that women may have produced more than 110,000 manuscripts during the Middle Ages, with around 8,000 still extant today. The study, titled “How Many Medieval and Early Modern Manuscripts Were Copied by Female Scribes? A Bibliometric Analysis Based on Colophons,” is a landmark in the field, utilizing cutting-edge bibliometric methods to offer a broad, quantitative assessment of women’s participation in manuscript production.

Unearthing the Hidden Contributions of Female Scribes

Historically, the role of women in the production of medieval manuscripts has been overshadowed by a prevailing narrative that focuses on male scribes. While some studies have looked at isolated scriptoria or regions to highlight female involvement, they have often been limited in scope, typically focusing on qualitative or anecdotal evidence. These studies were invaluable in uncovering specific examples of female scribes, but they lacked the breadth necessary to estimate the true scale of women’s contributions to manuscript culture. The recent study, however, has changed that by employing a novel approach to assess the gendered aspects of medieval scribal activity across a vast period and geographic scope.

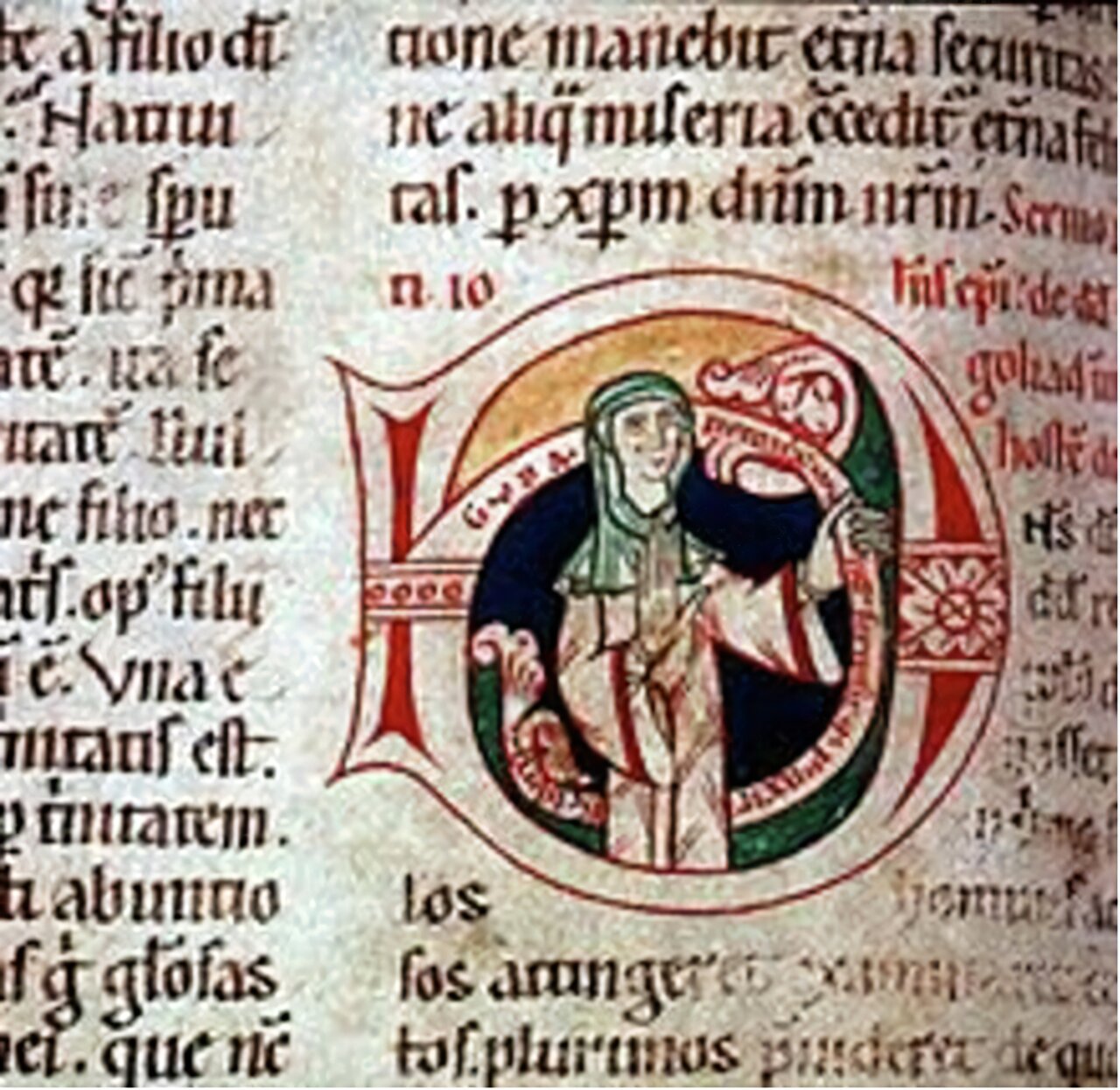

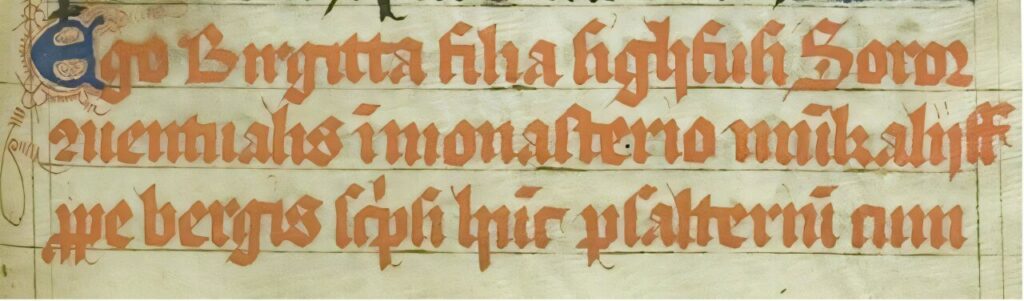

The study was built around the analysis of colophons—brief notes typically added at the end of a manuscript, often providing the name of the scribe, the place of production, the date, and, sometimes, even personal reflections or details about the manuscript’s creation. These inscriptions are a goldmine for researchers seeking to identify the gender of scribes, as they often include self-referential terms, names, and other distinctive markers that can confirm the scribe’s identity.

Methodology: The Colophon-Based Bibliometric Analysis

The researchers conducted a thorough bibliometric colophon analysis, examining a total of 23,774 manuscript colophons from institutional collections across Europe. Their goal was clear: to systematically count the instances where the scribe’s gender could be definitively identified and determine how many of these were female scribes.

Importantly, the researchers only counted colophons where the scribe’s gender could be conclusively established—meaning no ambiguity or unverified assumptions were allowed. This conservative approach led to the identification of 254 colophons directly linked to female scribes. While this number may seem small in comparison to the overall corpus of medieval manuscripts, it constitutes an essential first step in quantifying women’s contributions. The 1.1% figure represents a minimum estimate—meaning that the actual contribution could have been higher, but the researchers deliberately focused on verifiable evidence to avoid overstatement.

The analysis revealed several key patterns, including the surprising consistency of female involvement in manuscript production between 800 and 1400 CE. After 1400, however, the data showed a notable uptick in the number of manuscripts produced by women, especially in local, vernacular languages. This shift coincides with broader changes in medieval literacy, where manuscript production began to move beyond Latin to encompass regional languages, such as Old English, Old French, and other vernacular tongues.

A Monumental Contribution to Medieval Manuscript Culture

The study’s most striking revelation is the estimation that women may have produced at least 110,000 manuscripts over the medieval period, with 8,000 still surviving in libraries and archives today. While this figure remains a conservative estimate, it underscores a critical point: women were far more involved in manuscript production than previously thought. Known female scriptoria, or communities of female scribes, represent just a small fraction of this total, suggesting that there were likely other, previously unidentified groups of women engaged in manuscript copying across Europe.

One of the intriguing aspects of this finding is that much of women’s manuscript output remains hidden in plain sight. While some famous scriptoria, such as those at certain convents, are known to have had female scribes, the vast majority of women’s manuscripts have likely been overlooked or misattributed throughout history. This suggests that the study of female scribes has barely scratched the surface, and future research could yield even more surprising findings.

The Role of Women in Vernacular Manuscripts

One of the most compelling aspects of the study is its observation that after 1400 CE, female scribes were significantly more involved in producing manuscripts in vernacular languages. While Latin remained the dominant language of scholarship and religious texts throughout the medieval period, vernacular languages began to emerge as key mediums for literature, legal texts, and even historical chronicles. The increase in female scribal activity after 1400 coincides with the rise of this literary tradition, suggesting that women were more actively engaged in local literary cultures.

This shift also speaks to the broader societal changes of the late Middle Ages. The rise of urban centers, the spread of education, and the growing importance of local languages in both secular and religious life likely provided new opportunities for women to participate in manuscript production. The study opens up new avenues for exploring how women might have engaged with these texts, and whether they had distinct literary or cultural preferences in the texts they chose to copy.

Exploring the Socio-Political and Economic Contexts

Despite the wealth of new data, the study also raises several important questions about the socio-political and economic contexts that supported female manuscript production. What factors allowed certain women to become scribes, while others were excluded from such roles? What were the social and institutional frameworks that facilitated or hindered women’s participation in manuscript culture? These questions are crucial for understanding not only how women were able to contribute to the intellectual landscape of the Middle Ages but also why they did so.

In many cases, female scribes were likely confined to monastic or conventual settings, where they might have had access to education and resources. But there were also laywomen, such as those in urban centers or courtly environments, who may have had the opportunity to engage in manuscript production. Further research should investigate how these various factors—religious, cultural, and economic—shaped the opportunities available to women in different regions and time periods.

The study also suggests that parish, census, and institutional records could offer invaluable insights into the hidden networks of book production by women. Local records may provide more concrete evidence of women’s participation in manuscript production outside the well-known scriptoria, shedding light on areas of the medieval world where women’s work has been largely overlooked.

Looking Ahead: Mapping Women’s Contribution to Medieval Literacy

The study at the University of Bergen opens exciting new pathways for future research on the history of literacy and manuscript production. One crucial avenue will be the geographical and chronological mapping of female-authored colophons. By examining these texts across different regions and time periods, researchers can better understand how women’s roles in manuscript production evolved over time and whether specific regions or institutions were more supportive of female scribes.

Additionally, scholars should aim to analyze the types of texts that women copied. Were women more likely to produce religious texts, or were they involved in secular and literary works as well? How did gender influence the kinds of texts women chose to reproduce? By answering these questions, historians can gain deeper insights into the broader cultural and intellectual contributions of women to medieval society.

Conclusion: Rewriting History

The findings from the University of Bergen offer a new chapter in the history of medieval manuscript production, revealing a vibrant, previously underestimated role for women in shaping the literary culture of the Middle Ages. The conservative estimate of 1.1% may seem small, but it opens the door to a far richer, more complex understanding of medieval literacy.

By recognizing the contributions of female scribes, we not only enrich our understanding of medieval book culture but also begin to rewrite the history of intellectual labor in the Middle Ages, ensuring that women’s often-overlooked contributions are finally brought into the light. As future research unravels more about the networks, contexts, and texts associated with female scribes, we can expect to uncover even more fascinating stories of women’s engagement with the written word during one of history’s most dynamic and transformative periods.

Reference: Åslaug Ommundsen et al, How many medieval and early modern manuscripts were copied by female scribes? A bibliometric analysis based on colophons, Humanities and Social Sciences Communications (2025). DOI: 10.1057/s41599-025-04666-6