Deep within the rugged, red cliffs of Morocco’s Middle Atlas Mountains, a remarkable discovery has surfaced—one that is changing our understanding of dinosaur evolution. A collaborative team of paleontologists from the Natural History Museum in the U.K., the University of Birmingham, and Sidi Mohamed Ben Abdellah University in Morocco has unearthed the oldest known cerapodan dinosaur ever found. Their work, published in the journal Royal Society Open Science, not only pushes back the timeline of this ancient group of herbivores but also opens new chapters in the story of dinosaur evolution during a time shrouded in mystery.

So, what exactly did they find? And why does it matter so much? Let’s take a closer look at this exciting paleontological breakthrough.

What Are Cerapodans, and Why Are They Important?

Cerapodans were a diverse group of ornithischian dinosaurs, the so-called “bird-hipped” dinosaurs. These plant-eaters dominated prehistoric ecosystems during the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods. Familiar members of this group include some of the most iconic dinosaurs to ever walk the Earth: Iguanodons, Hadrosaurs (the “duck-billed” dinosaurs), and Ceratopsians like Triceratops. Despite their variety, cerapodans were typically small to medium-sized dinosaurs, often zipping around on two legs in a way that brings modern birds to mind.

But there’s been a problem. While fossilized footprints and tracks have told us that cerapodans were around in the Middle Jurassic period, actual bones—hard evidence of their bodies—have been painfully rare. Most of our knowledge of these creatures comes from the Cretaceous period, when they were abundant across the globe. What they were up to before that, and how they evolved into the successful group we know from later times, has remained a scientific enigma.

Until now.

The Discovery: A 168-Million-Year-Old Femur

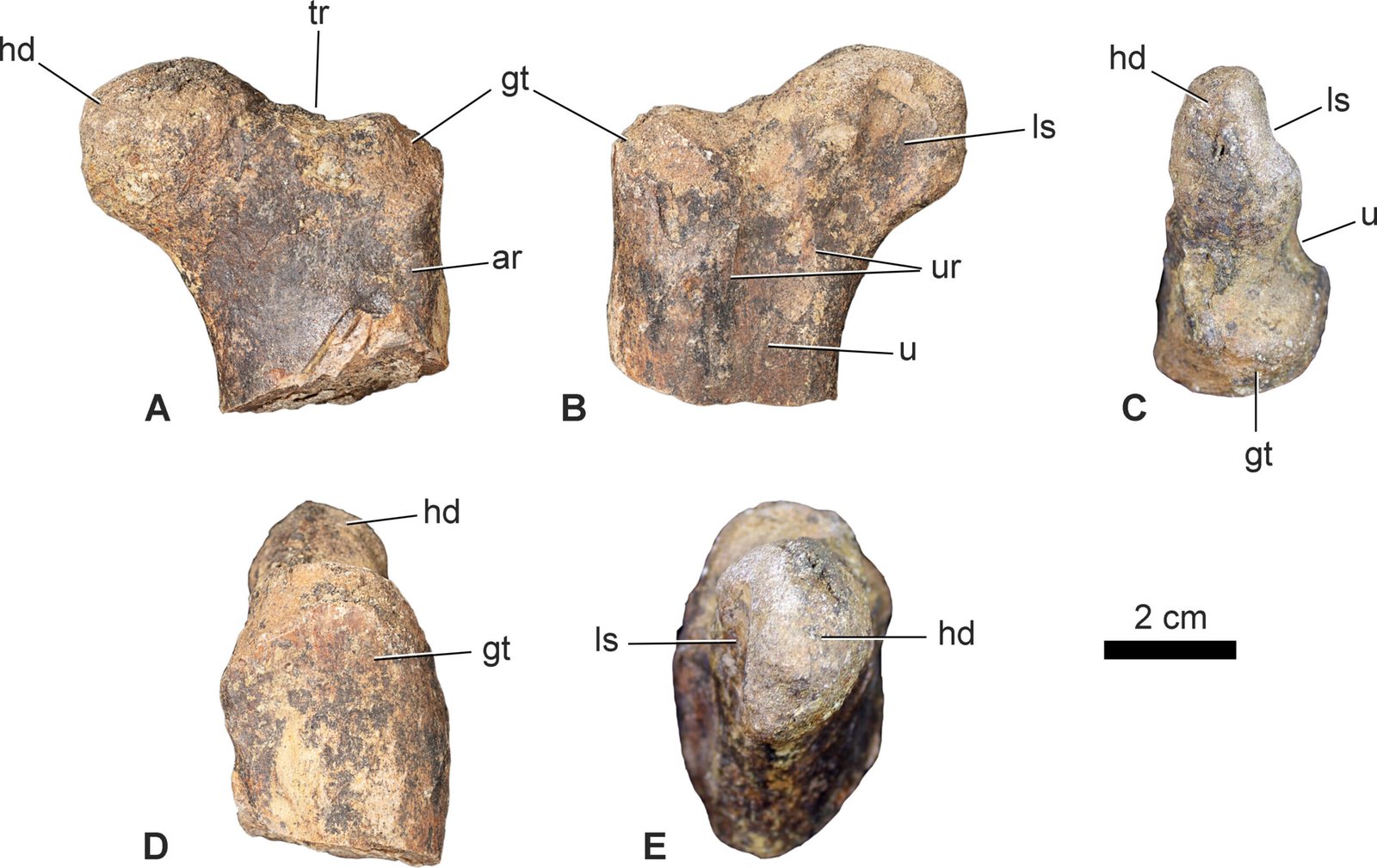

The team was working at a dig site in El Mers III Formation, a fossil-rich layer of rock from the Bathonian age, roughly 168 million years old. This rocky expanse in Morocco has already yielded some impressive finds, including the oldest ankylosaur fossils, but this time, the scientists found something that would make paleontological headlines: a fossilized femur, or upper leg bone, of a dinosaur they immediately recognized as a cerapodan.

The features of the bone were distinctive. Along the back of the femur, there was a deep groove—one of the telltale traits of cerapodan dinosaurs. The shape of the femoral head, where it connected to the hip, also matched what scientists would expect to see in this group. Together, these clues made it clear: this was no generic ornithischian. It was unmistakably a cerapodan, and it was older than any cerapodan bone found before.

How much older? This fossil beats the previous record-holder, an iguanodontian femur from England, by about two million years. Two million years might seem like a small margin in the vast stretches of deep time, but in evolutionary terms, it’s enough to rewrite entire chapters of history.

Why This Fossil Matters

The newly discovered femur is more than just an old bone. It’s a key piece of evidence that confirms long-standing theories suggesting that cerapodans began diversifying long before the Cretaceous period, when they eventually rose to dominance. Paleontologists had hypothesized that this group of dinosaurs was already branching out into new forms and niches in the Middle Jurassic, but without body fossils to prove it, these ideas remained speculative.

This find solidifies the timeline, showing that cerapodans were thriving and diversifying at least 168 million years ago. It suggests that they had enough evolutionary flexibility to survive and adapt to a wide range of environments—qualities that would later help them spread across ancient Earth and evolve into the many species we now recognize from the fossil record.

A Paleontological Goldmine in the Middle Atlas Mountains

The El Mers III Formation, where this discovery was made, is quickly becoming a treasure trove for paleontologists. The area’s Bathonian rock layers are rare. Much of the world lacks rock deposits from this Middle Jurassic window, which is why fossils from this time period are so hard to come by. The fact that these rocks are yielding significant finds is thrilling for scientists who have long grappled with gaps in the fossil record.

Not only was the oldest known ankylosaur found nearby, but now, with the addition of the earliest cerapodan bone, the Middle Atlas Mountains are proving to be an untapped reservoir of evolutionary history. Researchers believe there are more fossils waiting to be discovered in the region—fossils that could further illuminate how early dinosaurs lived, competed, and diversified.

Cerapodans: The Unsung Heroes of Dinosaur Evolution

While cerapodans may not have the fearsome reputation of the meat-eating theropods or the titanic size of sauropods, they represent one of the most successful branches on the dinosaur family tree. They evolved into a staggering variety of shapes and sizes, developing complex teeth for chewing tough vegetation, crests and horns for defense and display, and herding behaviors that made them some of the most socially sophisticated dinosaurs of their time.

The discovery of this ancient femur adds an important data point to the evolutionary timeline, suggesting that the traits that made cerapodans so successful—flexibility in diet, adaptability to different climates, and efficient locomotion—were already taking root in the Middle Jurassic.

Looking Ahead: More Discoveries on the Horizon

The discovery of this ancient cerapodan fossil isn’t the end of the story. In fact, it’s likely just the beginning. The research team is planning further excavations in the Middle Atlas Mountains, hopeful that they’ll uncover more fossils to help flesh out the skeleton of cerapodan evolution. Every new bone, tooth, or trackway has the potential to answer lingering questions about how these animals lived, moved, and interacted with their environments.

Could there be even older cerapodans buried beneath the Moroccan soil? Or entirely new species that defy our current classifications? The possibilities are tantalizing, and the paleontological world is watching closely.

Conclusion: A Glimpse Into the Ancient Past

With the unearthing of this 168-million-year-old femur, paleontologists have gained a crucial piece of evidence that confirms the early rise of cerapodan dinosaurs. This discovery doesn’t just push back their known existence—it reframes our understanding of how these dinosaurs evolved and thrived.

The Middle Atlas Mountains of Morocco are emerging as a vital window into the Middle Jurassic, a time period that has, until recently, remained frustratingly elusive. Thanks to the dedication and collaboration of scientists from around the world, we are getting closer to solving the mysteries of the early days of the dinosaurs.

One ancient bone at a time.

Reference: Susannah Maidment et al, The world’s oldest cerapodan ornithischian dinosaur from the Middle Jurassic of Morocco, Royal Society Open Science (2025). DOI: 10.1098/rsos.241624