Imagine standing in a vast, silent desert at midnight. The stars blaze in the sky, their faint glimmers reaching you across unimaginable gulfs of space and time. To your eyes, it seems as though the universe is mute, a quiet, distant expanse of celestial lights. But that is an illusion. The universe is alive with sound—not sound in the way we hear it with our ears, but a symphony of signals. Hidden in the darkness are whispers, pulses, and rhythms that we cannot hear without special instruments. These are radio waves, the language of the cosmos, and radio astronomy is how we listen to them.

Welcome to Radio Astronomy, where giant ears made of steel listen to the universe’s deepest secrets. Here, astronomers do not gaze through lenses but “listen” to the sky, tuning into a vast range of invisible frequencies. In this unseen spectrum, entire worlds are revealed—worlds beyond the reach of ordinary light. Radio astronomy has transformed our understanding of the cosmos, uncovering phenomena we could never have imagined: pulsars ticking like cosmic clocks, quasars blazing like the hearts of ancient galaxies, and signals from the birth of the universe itself.

This is a story of curiosity, invention, and discovery. It is a story of how we learned to listen to the universe—and what it told us in return.

The Hidden Symphony: Understanding Radio Waves

What Are Radio Waves?

In the electromagnetic symphony of the universe, radio waves are the longest and slowest notes. They are a form of electromagnetic radiation, like visible light, X-rays, or gamma rays, but they occupy a different part of the spectrum. The difference lies in their wavelength—the distance between wave peaks. Radio waves have wavelengths ranging from millimeters to kilometers. Because they are so much longer than visible light, they can pass through dust clouds that block optical telescopes, opening up regions of space previously hidden from view.

But radio waves are not just a scientific curiosity. They carry information—signals that tell stories about the universe’s structure, its violent events, and its ancient history. These waves are produced by all kinds of celestial objects: stars, planets, galaxies, black holes, and even the fading glow of the Big Bang.

Why Listen Instead of Look?

Why bother with radio waves when optical telescopes seem to do the job? After all, the Hubble Space Telescope has captured breathtaking images of distant galaxies and nebulae. But visible light tells only part of the story.

Imagine trying to understand an orchestra by watching musicians move their bows, but hearing none of the music. Radio waves are the music. They allow us to detect and study phenomena invisible to optical telescopes. Pulsars, for example, are rapidly spinning neutron stars that emit beams of radio waves with precise regularity. Quasars emit incredible amounts of radio energy as they devour matter near supermassive black holes. And the cold gas clouds from which stars are born emit faint radio signals that would otherwise be undetectable.

Radio astronomy gives us a deeper, more complete picture of the universe—its energy, its origins, and its unseen dramas.

A Brief History of Radio Astronomy: From Static to Science

The Accidental Discovery

Like many great discoveries, radio astronomy began by accident. In the early 1930s, Karl Jansky, an engineer at Bell Telephone Laboratories, was investigating sources of radio static that might interfere with transatlantic radio telephone service. He built a massive rotating antenna—dubbed “Jansky’s merry-go-round”—to hunt down sources of interference. Most of the noise he found came from thunderstorms, both local and distant.

But there was something else. Jansky detected a steady, faint hiss that peaked every 23 hours and 56 minutes—the length of a sidereal day, which tracks Earth’s rotation relative to the stars rather than the Sun. He realized the signal was coming from beyond the Earth. Specifically, it originated from the direction of the constellation Sagittarius, home to the center of our Milky Way galaxy.

Jansky had stumbled upon radio waves from outer space. Yet his discovery was met with indifference by astronomers of the time. It wasn’t until the late 1930s that Grote Reber, an amateur radio operator and engineer, built the first purpose-built radio telescope in his backyard. His work marked the true birth of radio astronomy.

Early Advances

In the 1940s and 1950s, radio astronomy began to grow. Scientists realized that radio waves could reveal powerful sources of energy: supernova remnants, galaxies, and mysterious objects that emitted intense radio emissions. They discovered radio galaxies—galaxies that emit enormous amounts of energy in radio frequencies, often powered by supermassive black holes.

One of the most astonishing discoveries was that of pulsars in 1967 by Jocelyn Bell Burnell and Antony Hewish. These rapidly rotating neutron stars emitted radio pulses with eerie precision, like cosmic lighthouses ticking across space.

And then, in 1965, Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson, while calibrating a radio antenna for Bell Labs, stumbled upon a persistent, isotropic noise that could not be accounted for. They had inadvertently detected the Cosmic Microwave Background Radiation—the faint afterglow of the Big Bang itself. It was a discovery that cemented the Big Bang theory as the leading explanation for the origin of the universe.

How Radio Telescopes Work: Giant Ears to the Sky

Anatomy of a Radio Telescope

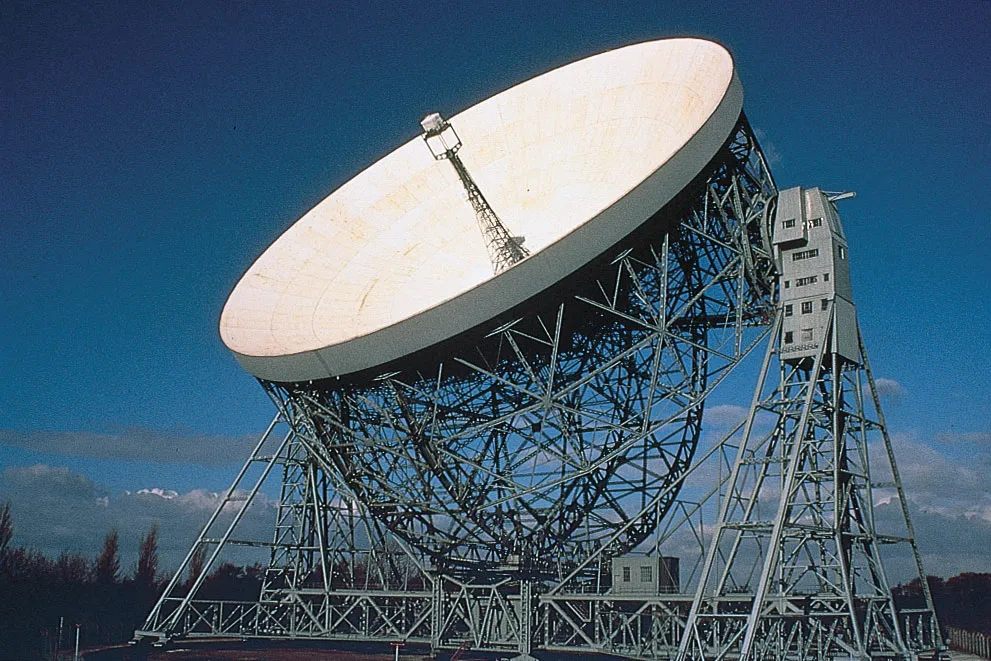

Radio telescopes do not look like traditional telescopes. Instead of lenses or mirrors to focus light, they use large parabolic dishes—reflecting surfaces that collect and focus radio waves onto a receiver. The receiver converts the waves into electrical signals that can be analyzed by computers.

The size of a radio telescope is crucial. Radio waves have much longer wavelengths than visible light, so larger dishes are needed to collect enough energy to detect faint signals. That’s why some radio telescopes are enormous.

Notable Radio Telescopes

- The Very Large Array (VLA) in New Mexico consists of 27 dish antennas arranged in a Y-shaped formation. Each dish is 25 meters in diameter, and together they can simulate a single telescope with a resolution equivalent to a dish 36 kilometers across.

- Arecibo Observatory in Puerto Rico was once the largest single-aperture radio telescope, with a dish 305 meters across (until its collapse in 2020). Arecibo helped discover the first binary pulsar and contributed to SETI (Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence) efforts.

- FAST (Five-hundred-meter Aperture Spherical Telescope) in China is currently the largest single-dish radio telescope on Earth. FAST has the sensitivity to detect signals from distant galaxies and is leading new research into pulsars and fast radio bursts.

- ALMA (Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array) in Chile is a collection of 66 high-precision antennas working together in the high desert of the Atacama region. ALMA observes in the millimeter and submillimeter wavelengths, perfect for studying cold gas and dust clouds where stars and planets are born.

Interferometry: Combining Many Ears

One of radio astronomy’s most brilliant techniques is interferometry, where multiple radio telescopes are linked together across vast distances to form a virtual telescope as large as the distance between them. This increases resolution dramatically. The Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) used this technique to produce the first-ever image of a black hole in 2019.

The Universe in Radio Waves: What We Have Learned

Pulsars: Cosmic Timekeepers

Pulsars are neutron stars that emit beams of radiation from their magnetic poles. As they spin, these beams sweep across space, and if one crosses Earth, we detect a regular pulse of radio waves. Some pulsars are so precise in their rotations that they rival atomic clocks.

Pulsars have allowed astronomers to test Einstein’s theory of general relativity, study the extreme physics of neutron stars, and even search for gravitational waves by monitoring their rhythmic signals.

Quasars and Active Galactic Nuclei

Quasars are among the most energetic and distant objects in the universe. They are powered by supermassive black holes that consume matter, releasing vast amounts of energy, including radio waves. Radio observations of quasars have shown jets of particles traveling near the speed of light, stretching for millions of light-years.

Quasars helped map the structure of the early universe and provided clues about how galaxies evolve over billions of years.

Cosmic Microwave Background: The Echo of Creation

The Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) is the faint glow of radiation left over from the Big Bang. It fills the entire universe and has a temperature of just 2.7 Kelvin—barely above absolute zero. Radio telescopes tuned to microwave frequencies have mapped the CMB in exquisite detail.

These maps have revealed tiny fluctuations in temperature that represent the seeds of all structure in the universe: galaxies, clusters, and the cosmic web itself.

Fast Radio Bursts: Cosmic Mysteries

In recent years, astronomers have detected strange, powerful flashes of radio energy known as Fast Radio Bursts (FRBs). These events last mere milliseconds but release as much energy as the Sun produces in a day. Some FRBs repeat; others seem to come from distant galaxies billions of light-years away.

Their origin remains one of the biggest mysteries in astrophysics. Are they from magnetars (highly magnetized neutron stars)? Colliding black holes? Or perhaps something stranger? Radio astronomy is at the forefront of solving this cosmic puzzle.

The Search for Life: SETI and Beyond

Radio astronomy is also our best hope for detecting intelligent life beyond Earth. The Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI) uses radio telescopes to listen for artificial signals—broadcasts or beacons from distant civilizations.

The logic is simple: radio waves are a natural choice for interstellar communication. They travel vast distances with minimal loss, can carry enormous amounts of information, and are relatively easy to produce and detect. Projects like Breakthrough Listen are using the world’s most powerful radio telescopes to scan nearby stars and galaxies for signs of artificial transmissions.

So far, the search has turned up nothing definitive, but it continues with renewed vigor. If an alien civilization is out there, radio waves may be the first sign we receive.

The Future of Radio Astronomy: New Horizons

The future of radio astronomy is as vast as the universe it studies. New telescopes and technologies promise to unlock more cosmic secrets.

The Square Kilometre Array (SKA)

The Square Kilometre Array (SKA) will be the largest radio telescope network ever constructed, with thousands of antennas spread across Australia and South Africa. It will have a collecting area of over one square kilometer, giving it unprecedented sensitivity.

The SKA will map billions of galaxies, study the epoch of reionization (when the first stars and galaxies formed), and search for signs of life on distant worlds.

Space-Based Radio Telescopes

Earth’s atmosphere limits some radio observations. In the future, space-based radio telescopes may offer clearer views of the universe. Concepts for arrays of radio antennas placed on the far side of the Moon—shielded from Earth’s radio noise—are under discussion.

These observatories could probe the cosmic “dark ages,” a time before the first stars lit up the universe.

Conclusion: Listening to the Cosmic Choir

Radio astronomy has transformed our understanding of the universe. Where once we saw a silent night sky, we now hear a symphony of signals: pulsars ticking, galaxies roaring, black holes whispering their secrets across the void.

It reminds us that the universe is not just something to be seen—it is something to be heard. And in listening, we have learned not only about distant stars and galaxies but about the very nature of space, time, and our place in the cosmos.

We are listeners in the grand cosmic choir, our radio telescopes like finely tuned ears pressed to the infinite. And the universe? The universe is singing.