Beneath the cold, distant glow of Saturn’s rings lie two worlds that have captured human imagination like few others in the solar system. Enceladus and Titan—two very different moons orbiting a gas giant nearly a billion miles away—hide secrets beneath their frozen skins. Secrets that whisper possibilities: oceans under ice, water warmed by strange energies, and maybe, just maybe, life beyond Earth.

In a cosmos brimming with mystery, these two moons stand out as real contenders for harboring the ingredients for life. Enceladus dazzles us with its icy geysers, spraying material into space from a hidden ocean below. Titan, cloaked in a dense golden atmosphere, hosts rivers, lakes, and seas of liquid methane on its surface, while deep underground, a massive water ocean churns in silence.

What follows is a journey through these two alien worlds, a dive beneath their frozen exteriors to explore the oceans that could change everything we thought we knew about life in the universe.

The Realm of the Ringed Giant

Before we dive into the waters of Enceladus and Titan, we need to understand the colossal world they orbit: Saturn. The second-largest planet in our solar system, Saturn is a gas giant shrouded in mystery and beauty. Its defining feature, the brilliant rings, make it one of the most recognizable objects in the night sky.

But Saturn is more than a pretty face. It’s a system—a miniature solar system in itself—with at least 146 moons (and counting). Among them are small, irregular chunks of rock and ice, but two of its largest, Enceladus and Titan, offer environments that scientists have come to believe might harbor life.

Orbiting this gas giant, Enceladus and Titan are part of a vast, dynamic system influenced by Saturn’s gravity, magnetic field, and radiation belts. And in these two moons, we find liquid water oceans far from the warmth of the Sun, kept warm by alien forces.

Enceladus—The Shining Jewel of the Outer Solar System

A Moon of Ice and Mystery

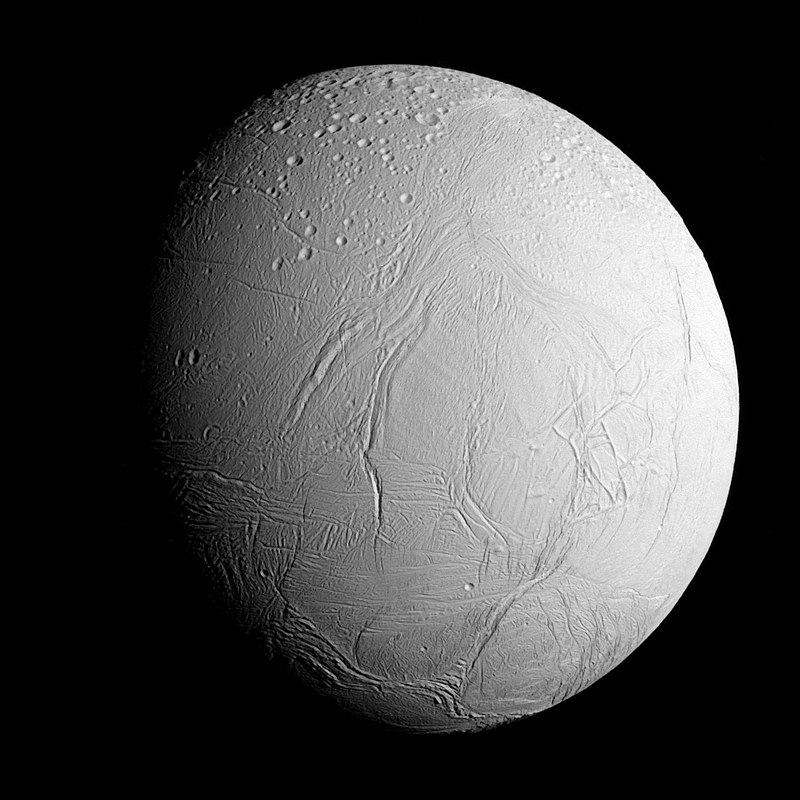

Enceladus is not the biggest moon of Saturn, not by a long shot. Measuring just 313 miles (504 kilometers) across, it could fit comfortably within the state of Arizona. And yet, despite its small size, Enceladus commands enormous scientific interest. It gleams like a cosmic snowball, its surface one of the brightest objects in the solar system, reflecting nearly all sunlight that strikes it.

When the Voyager spacecraft flew by Saturn in the 1980s, Enceladus was just another frozen world. But everything changed when the Cassini spacecraft arrived in 2004. As Cassini looped through the Saturn system, Enceladus revealed its astonishing secret: it was spraying plumes of ice and water vapor into space.

The Discovery That Changed Everything

In 2005, Cassini made a daring close pass over Enceladus’ south pole. What it saw defied expectations. Gigantic geysers erupted from four parallel fractures, later nicknamed the “Tiger Stripes.” These fissures vented water vapor, icy particles, salts, and organic molecules into space. Some of the particles even escaped Enceladus’ weak gravity, contributing to Saturn’s E ring.

But where was this water coming from? Scientists quickly realized the source had to be a subsurface ocean of liquid water beneath Enceladus’ icy crust.

The Ocean Beneath

By analyzing the composition of the plumes, Cassini found clear evidence of liquid water mixed with salts and simple organic molecules. But the most profound discovery came in 2015, when scientists detected molecular hydrogen in the plumes—a potential energy source for microbial life. On Earth, hydrothermal vents at the bottom of our oceans use similar processes to sustain entire ecosystems, independent of sunlight.

Enceladus’ ocean is thought to be global, lying beneath an ice shell that’s thinner at the south pole (where the Tiger Stripes are located) and thicker elsewhere. Tidal flexing caused by Saturn’s immense gravity keeps the interior warm, and likely fuels hydrothermal activity at the ocean floor.

If there are hydrothermal vents on Enceladus, they may offer the same life-sustaining chemical reactions that sparked life in Earth’s deep oceans.

Life’s Ingredients in Enceladus’ Ocean

What’s in the Plumes?

Cassini flew directly through the plumes of Enceladus, sampling their chemical composition. It found:

- Water vapor

- Ice grains

- Salts (like sodium chloride, familiar to us as table salt)

- Simple organic molecules (carbon-based)

- Molecular hydrogen (H2)

Molecular hydrogen was the key discovery. On Earth, hydrogen serves as food for microbes living around hydrothermal vents. These microbes use a process called methanogenesis, combining hydrogen with carbon dioxide to produce methane and energy. Such life forms do not require sunlight—just chemical energy.

Could Life Exist There?

Enceladus has three crucial ingredients for life as we know it:

- Liquid Water: Essential for all known life.

- Energy Sources: Provided by hydrothermal activity and molecular hydrogen.

- Organic Chemistry: The building blocks of life are present in its plumes.

With all these components, it’s possible that Enceladus’ ocean harbors microbial life. It may be simple and single-celled, like Earth’s archaea, or something entirely novel.

Enceladus invites us to wonder: is life a rare cosmic accident, or a common consequence of water and chemistry?

Titan—The Alien Earth

A World Like No Other

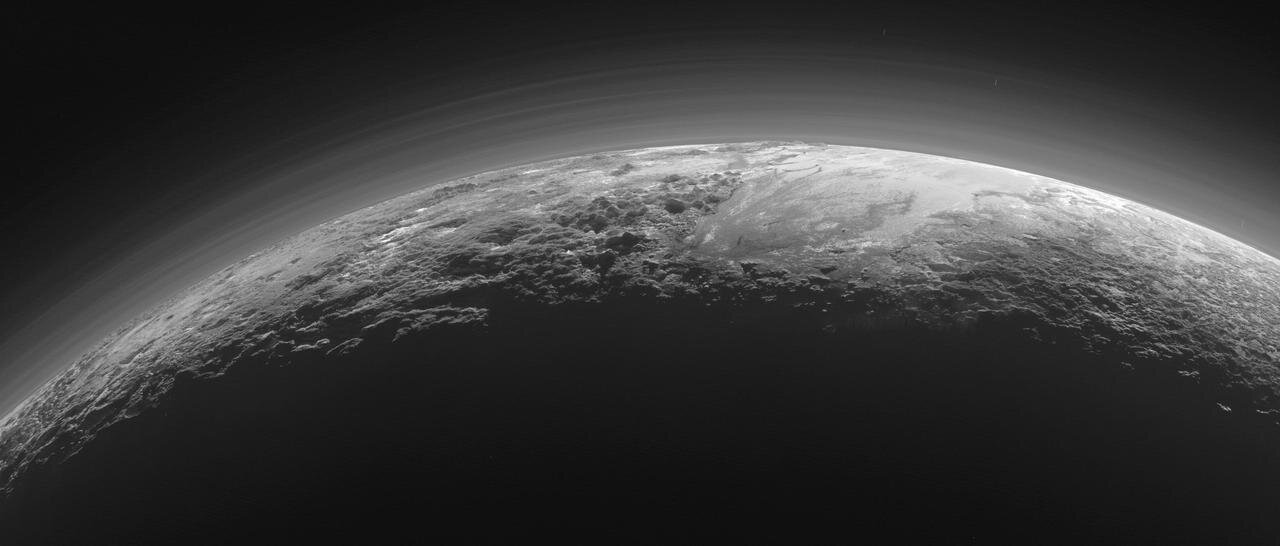

While Enceladus is a sparkling jewel of ice, Titan is shrouded in mystery. It’s the second-largest moon in the solar system, larger than the planet Mercury. And unlike any other moon, Titan has a thick atmosphere—so dense that it hides its surface from view.

Titan’s atmosphere is mostly nitrogen, like Earth’s, but it’s laced with methane and ethane. Sunlight and cosmic rays break apart these molecules, creating a complex haze of organic compounds that drift down to the surface.

But Titan’s real shock comes when we pierce that golden fog.

Lakes, Rivers, and Seas—But Not of Water

Cassini’s radar revealed a landscape eerily familiar: rivers snake across the surface, carving valleys; vast lakes and seas stretch along the poles; it even rains on Titan. But here, the rivers and lakes aren’t filled with water—they’re filled with liquid methane and ethane. The temperatures on Titan’s surface hover around -290 degrees Fahrenheit (-179 degrees Celsius), far too cold for liquid water.

Instead, Titan has a methane cycle—just like Earth’s water cycle—with rain, rivers, lakes, and evaporation. Titan is, in many ways, an analog of early Earth, only far colder and made of different substances.

The Subsurface Ocean

Beneath Titan’s icy crust, however, scientists believe there is another ocean—one made of liquid water mixed with ammonia. Gravity measurements from Cassini suggest that Titan’s outer shell floats on this global ocean, much like Earth’s crust floats on the mantle.

This ocean may be sandwiched between layers of ice, but it’s deep and vast. Ammonia acts as antifreeze, lowering the freezing point of water and keeping it liquid even in Titan’s frigid conditions.

And like Enceladus, Titan’s ocean is heated by tidal forces and possibly by the decay of radioactive elements within its core.

The Chemistry of Life on Titan

Alien Oceans, Alien Chemistry

Titan presents a double mystery. On its surface, complex organic chemistry is already happening in its methane lakes and in the haze that blankets the moon. But deep below, its subsurface ocean might offer a more familiar home for life as we know it.

Scientists are tantalized by the possibility of two very different kinds of life on Titan:

- Water-based life in its hidden subsurface ocean.

- Methane-based life on its cold, hydrocarbon-rich surface.

Methane-based life would be a true alien form of biology. On Earth, cell membranes are made of lipids that work well in water. But in the cold methane lakes of Titan, scientists speculate that alien life could have cell membranes made from totally different compounds, such as acrylonitrile, forming structures called “azotosomes.”

Building Blocks from the Sky

Titan’s thick atmosphere is a factory for organic molecules. Ultraviolet light breaks apart methane, allowing carbon atoms to recombine into ethane, acetylene, and even complex prebiotic molecules like tholins. These complex organics rain down on Titan’s surface, coating the dunes and filling the lakes.

On Earth, life may have started in a similar organic soup. Could Titan’s surface chemistry be the first steps toward life?

Exploring the Hidden Oceans

Cassini’s Legacy

Cassini’s mission ended in 2017, when it plunged into Saturn’s atmosphere to avoid contaminating Enceladus or Titan. But the data it sent back continues to reshape our understanding of these moons.

Cassini carried the Huygens probe, which descended through Titan’s atmosphere in 2005. Huygens landed on a riverbed-like plain, surrounded by pebbles made of water ice, providing our first close-up look at Titan’s surface.

Future Missions:

- Dragonfly (NASA): Slated for launch in 2027, Dragonfly is a nuclear-powered drone that will fly through Titan’s thick atmosphere, exploring different locations. It will search for prebiotic chemistry and potential biosignatures.

- Enceladus Orbilander (NASA Concept): A proposed mission that would orbit Enceladus, analyze its plumes in more detail, and eventually land on the surface near the Tiger Stripes. The goal? To look for direct evidence of life.

The Challenges of Exploration

Exploring these moons isn’t easy. Enceladus’ surface is icy and treacherous, and its plumes are both an opportunity and a hazard. Titan’s dense atmosphere and freezing temperatures demand tough, reliable spacecraft.

But the rewards are immense. These oceans are within our technological reach, and what we find there could redefine life itself.

What If We Find Life?

The Implications

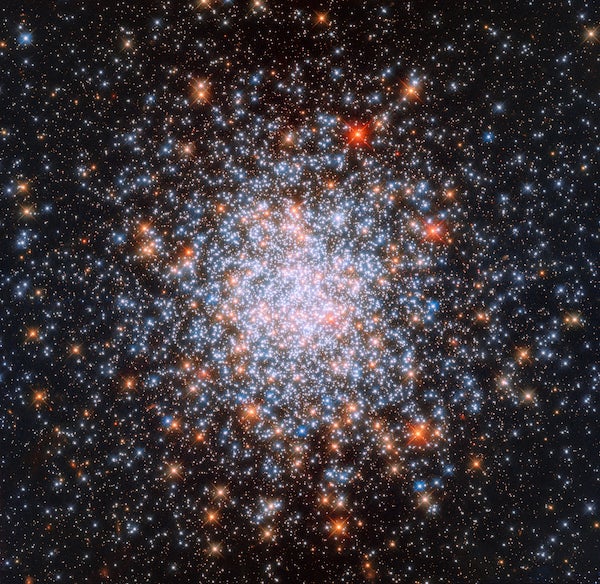

If we discover life—past or present—in Enceladus’ ocean or Titan’s seas, it would be a turning point in human history. It would suggest that life isn’t unique to Earth. If it arose twice in our own solar system, it may be common across the galaxy.

- Enceladus Life: Microbial life in a subsurface ocean would show that life can emerge in dark, sunless seas powered by chemistry alone.

- Titan Life: A methane-based biosphere would shatter our assumptions about what life can be. It would be life as we don’t know it—an entirely new form of biology.

Philosophical Questions

Finding life on Enceladus or Titan would spark philosophical and ethical debates. Would we protect these alien ecosystems? What if we accidentally contaminate them with Earth microbes? And what would it mean for our place in the universe?

Conclusion: The Call of the Alien Oceans

Enceladus and Titan stand as testaments to the richness and diversity of worlds beyond Earth. Their hidden oceans challenge our understanding of life and beckon us to explore further.

Enceladus, with its icy geysers spraying samples into space, is inviting us to taste the water of another world. Titan, with its rivers of methane and deep water ocean, offers a window into a different kind of chemistry, and possibly, life unlike anything we’ve ever imagined.

As we look to the stars and plan future missions, these moons are not just destinations—they are frontiers in the greatest journey of all: the search for life beyond Earth.

We stand on the shore of an endless cosmic sea. And Enceladus and Titan are the first islands we’ve glimpsed on the horizon.