Amid the rugged escarpments and ochre-stained cliffs of Australia’s northeastern Kimberley region, a remarkable discovery is shedding new light on the rich artistic legacy of ancient Aboriginal cultures. In a groundbreaking study published in Australian Archaeology, archaeologist Dr. Ana Paula Motta, in collaboration with the Balanggarra Aboriginal Corporation, has unveiled a previously unrecognized style of rock art. The newly identified “Linear Naturalistic Figures” (LNF) bring with them a reimagined understanding of the artistic, environmental, and social evolution of the Kimberley landscape during the mid-to-late Holocene.

This revelation not only deepens the aesthetic and historical complexity of one of the world’s oldest continuous cultures—it also challenges long-standing assumptions about the artistic timeline of Australia’s First Nations people.

A Forgotten Layer in a Canvas of Time

The Kimberley region of Western Australia is often described as a vast open-air gallery. From sweeping sandstone overhangs to weathered cave walls, this region is home to an unparalleled concentration of Indigenous rock art, spanning tens of thousands of years. These motifs are more than images—they are cultural documents, spiritual testimonies, and ecological records.

For decades, scholars have cataloged these artworks into stylistic phases, the earliest of which—known as the Irregular Infill Animal Period (IIAP)—dates back to the late Pleistocene, between 17,200 and 13,000 years ago. This style is distinguished by detailed, dynamic animal representations, often infilled with vibrant pigments and irregular brushstrokes.

But during the ambitious Kimberley Visions project, which documented over 1,100 archaeological sites—including 151 with more than 4,200 individual rock art motifs—Dr. Motta and her team noticed something that didn’t quite fit.

“We found that many of the animal motifs, initially labeled as IIAP, diverged from its core features,” she explains. “They lacked the elaborate infills and expressive poses typical of IIAP. Their simplicity and consistency suggested something different—something later.”

The Emergence of Linear Naturalistic Figures

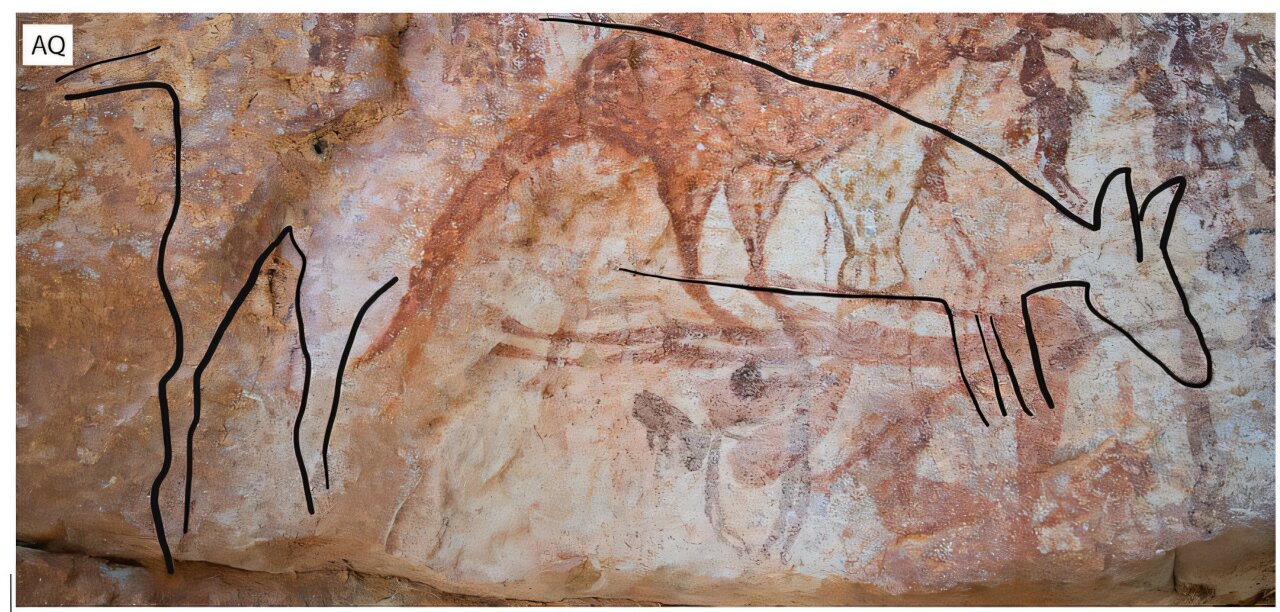

Upon closer analysis of 98 motifs from 22 sites in the Drysdale and King George River catchments, Dr. Motta and her team identified a new, cohesive rock art tradition. These images, once misclassified, revealed an emergent stylistic identity—the Linear Naturalistic Figures, or LNF.

Unlike the older IIAP imagery, LNF art is characterized by minimalist linear outlines, often devoid of infill. These animals are shown in static profile rather than dynamic action. The result is a quieter, more reserved visual language—almost contemplative in its stillness.

Most LNF images represent macropods: kangaroos, wallabies, and their relatives. These creatures dominate both the ancient and modern Australian landscape and held deep symbolic and practical value for Aboriginal communities. Their frequent depiction is no accident.

What makes the LNF style truly fascinating is its regional coherence. Across the two river catchments, the motifs fall into two distinct types: geometric LNF, which feature angular limbs and abstract forms devoid of anatomical details, and naturalistic LNF, whose figures show clearer musculature, facial features, and other lifelike elements. This internal variation hints at an evolving artistic intent and a nuanced visual vocabulary within the LNF corpus.

Unraveling the Timeline of Expression

Dating rock art is notoriously difficult. Without organic pigments that can be carbon-dated, archaeologists often rely on stratigraphy, stylistic superimpositions, and contextual evidence. In the case of LNF, its position relative to other styles in the Kimberley sequence was telling.

The LNF motifs are often painted over earlier IIAP, Gwion, and Static Polychrome artworks—styles known to span from around 17,000 to 9,000 years ago. However, LNF images also appear beneath or alongside Wanjina art, a style associated with ancestral beings and dating from around 5,000 years ago to the present.

This places the LNF style in a transitional window—between 9,000 and 5,000 years ago—precisely during the mid-to-late Holocene, a time of environmental and social transformation.

Rock Art as a Response to a Changing World

What catalyzed this return to naturalistic, zoomorphic imagery after a long period dominated by anthropomorphic and symbolic art styles?

Dr. Motta believes the answer lies in the broader context of Holocene life in northern Australia. “By this time,” she notes, “sea levels had stabilized, stone tool technologies were evolving, and linguistic and social landscapes were becoming more fragmented and regionally distinct.”

In other words, the LNF art emerged during a period of increasing complexity, as mobile hunter-gatherer groups began to settle into more defined territories. With growing social differentiation and environmental stabilization, rock art may have been enlisted as a tool—not just for storytelling or decoration—but for communication, negotiation, and identity formation.

“The recurrence of large animal motifs, especially macropods, suggests a reassertion of shared ecological and cultural values,” Dr. Motta explains. “These animals could have functioned as totems or symbolic anchors in a time of profound transition.”

Totems, Territory, and Identity

Among Australia’s First Nations peoples, the bond between humans, animals, and the land runs deeper than mere subsistence. In traditional Aboriginal cosmology, the Dreaming—an eternal spiritual continuum—shapes the identities of all beings. Within this sacred framework, humans and animals emerge from the same ancestral source and remain intertwined through totemic systems.

In these systems, particular animal species become linked to specific clans, law systems, and ceremonial roles. Thus, the LNF depictions of kangaroos and wallabies may not simply reflect the practical significance of these creatures as food sources. They may also have marked territory, recorded origin myths, or affirmed the ancestral relationships binding people to place and spirit.

“These rock paintings are part of a broader spiritual ecosystem,” says Dr. Motta. “They speak of belonging, movement, and survival—not just in the physical world, but in the cosmological one.”

A Dialogue Through Time

The superimpositions found in Kimberley’s rock shelters are like whispers layered across generations. Artists painted over their predecessors’ works not to erase them, but to enter into dialogue with them. In this sense, the LNF figures are both successors and respondents—echoes of an older artistic voice reframed for a new epoch.

One of the more compelling elements of LNF art is its restraint. Compared to the flamboyant coloration of Static Polychrome figures or the intricate body decorations of Gwion spirits, LNF motifs are subdued and almost meditative. This simplicity may represent a deliberate aesthetic choice, signaling a philosophical shift—a grounding in the tangible, physical world after millennia of abstraction.

Cultural Partnership and Ethical Archaeology

Central to the success of this study was the partnership with the Balanggarra Aboriginal Corporation, whose custodianship of the land provides critical cultural insight and ethical direction for archaeological work.

For the Balanggarra people, these artworks are not merely relics of the past. They are enduring expressions of identity, land ownership, and spiritual continuity. Collaborative research like the Kimberley Visions project reflects a growing movement in archaeology that prioritizes Indigenous leadership, storytelling, and sovereignty.

Reframing History Through New Eyes

The discovery of the Linear Naturalistic Figures is more than an academic reclassification. It invites us to re-examine our assumptions about the past—not as a monolithic narrative, but as a shifting mosaic of responses to changing environments, values, and relationships.

It also reminds us of the extraordinary depth of Australia’s cultural heritage. Long before the construction of cities or the invention of writing, Aboriginal Australians were painting, carving, singing, and dancing their world into being. The LNF style is but one verse in this vast and ongoing songline.

The Unfinished Story of Kimberley Rock Art

As researchers continue to analyze the thousands of motifs recorded during the Kimberley Visions project, more revelations are sure to come. New technologies such as 3D scanning, pigment analysis, and geospatial modeling promise to deepen our understanding even further.

Yet for all its sophistication, the most important element in this work remains human connection. It is the respect for knowledge passed through generations, the collaborative spirit of science and community, and the enduring awe for a land whose stories are etched into stone.

In every simple outline of a kangaroo or curve of a tail lies a legacy that stretches across millennia—a testimony to resilience, imagination, and the intimate dance between humanity and the land it calls home.

Reference: Ana Paula Motta et al, Linear Naturalistic Figures: a new Mid-to-Late Holocene Aboriginal rock art style from the northeast Kimberley, Australia, Australian Archaeology (2025). DOI: 10.1080/03122417.2025.2457860

Loved this? Help us spread the word and support independent science! Share now.