How does the brain store memories? It’s a question that has intrigued scientists and philosophers for centuries. Now, groundbreaking research from Scripps Research offers an extraordinary glimpse into the living blueprint of memory formation, mapping the cellular and subcellular changes that unfold as memories are made. The study, published in Science, doesn’t just offer answers—it rewrites some of the foundational rules of neuroscience.

For decades, neuroscientists have leaned on the famous adage, “Neurons that fire together, wire together,” to explain how memories and learning occur. But what if that’s not the whole story? What if the brain’s memory system is far more adaptable, intricate, and surprising than we ever imagined? This new research suggests just that.

Memory in High Definition: The Power of Advanced Tools

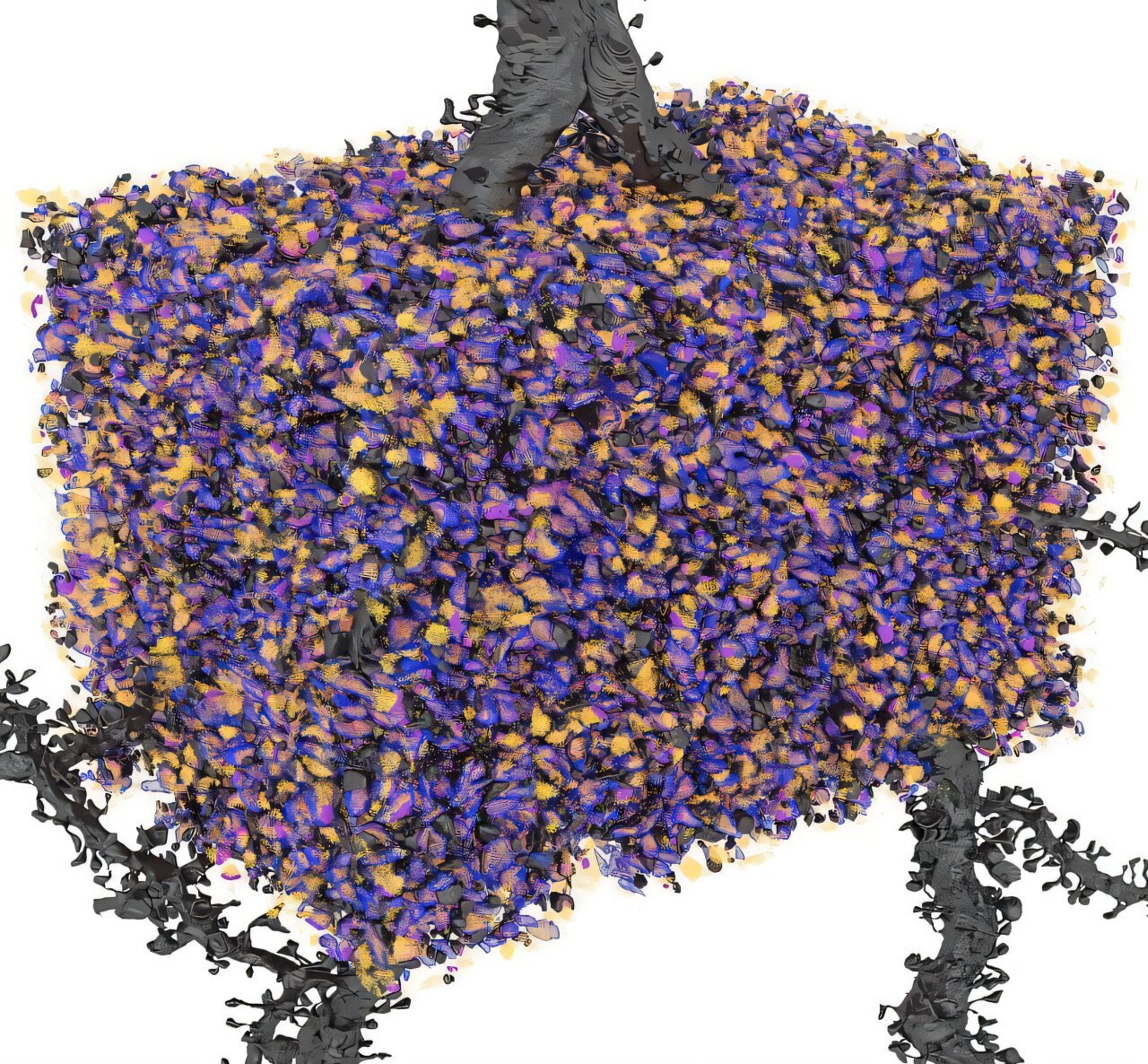

The team at Scripps Research, led by Marco Uytiepo and Anton Maximov, Ph.D., combined cutting-edge technologies to pull off a feat that would have been science fiction just a few years ago. They used advanced genetic labeling techniques, 3D electron microscopy, and artificial intelligence (AI) to reconstruct a hyper-detailed, nanoscale wiring diagram of neurons in the hippocampus—the brain’s memory hub.

Their focus was on a critical window of time: about one week after the mice underwent a learning task. This was a sweet spot in the memory-making process, a period after initial memory encoding but before the long-term storage mechanisms take over. By choosing this exact moment, the researchers captured the brain mid-transformation, revealing the physical changes that help turn experiences into lasting memories.

Multi-Synaptic Boutons: The Brain’s Secret Communication Hubs

One of the study’s most striking discoveries involves something called multi-synaptic boutons. In simple terms, a bouton is a point on a neuron’s axon that forms a synapse—a connection where signals are passed to another neuron. Traditionally, one bouton links to one post-synaptic partner. But in this study, the researchers found that neurons forming a memory trace often sprouted multi-synaptic boutons—specialized axonal structures capable of connecting with multiple neurons at once.

Imagine a speaker delivering a message not to a single listener but to an entire room, all at the same time. That’s the kind of expansive communication multi-synaptic boutons allow. This unique structure suggests a greater degree of flexibility and efficiency in how neurons encode and distribute information. It’s a level of multitasking that points to a brain architecture far more versatile than previously assumed.

And these weren’t random connections either. The boutons appeared to play an important role in routing information to different targets, enabling the flexibility that earlier functional studies hinted at but hadn’t been able to pinpoint on a structural level—until now.

Challenging the Old Guard: A New Model for Memory Formation

Perhaps the most paradigm-shifting finding from this research is what wasn’t found. Contrary to long-held theories, the neurons involved in forming a memory trace weren’t preferentially connected to each other. This flies in the face of the long-standing Hebbian theory, which holds that simultaneous activation strengthens direct connections between neurons.

In this new study, the absence of preferential connectivity suggests a different principle is at work. Rather than building isolated “cliques” of closely interconnected neurons, the brain may form memory traces through more complex and distributed networks. Instead of “neurons that fire together, wire together,” the process might be more like “neurons that fire together, diversify their messages to maximize flexibility and adaptability.”

Energy on Demand: Cellular Powerhouses Step Up

Memory isn’t just about communication—it’s also about energy. The study revealed that neurons involved in memory formation reorganized specific intracellular structures, including mitochondria—the power generators of the cell. This reorganization suggests that neurons ramp up their energy supplies to meet the heightened demands of memory encoding and processing.

These metabolic changes ensure that memory-related neurons can sustain increased activity, maintain plasticity, and strengthen the connections that support learning. Without this enhanced energy support, the physical changes required for memory formation might never get off the ground.

Astrocytes: The Unsung Heroes of Memory

Neurons often take center stage in discussions of brain function, but they don’t act alone. In this study, researchers found that neurons involved in learning exhibited enhanced interactions with astrocytes, the star-shaped glial cells that provide crucial support.

Astrocytes have traditionally been cast in a supporting role, maintaining the balance of chemicals in the brain and helping with nutrient delivery. But in recent years, their reputation has undergone a renaissance. These cells now appear to be active participants in modulating neural circuits and facilitating plasticity.

The heightened neuron-astrocyte interactions observed in this study suggest that astrocytes may play an underappreciated role in memory consolidation. They might help regulate the extracellular environment or supply metabolic resources precisely where and when they’re needed.

The Tools Behind the Breakthrough: A New Age of Brain Science

None of these revelations would have been possible without the marriage of innovative technologies. The team at Scripps deployed advanced genetic tools to permanently label the neurons activated during learning tasks. This made it possible to track specific neurons and their networks long after the initial experience had occurred.

Next, they used 3D electron microscopy to produce ultra-high-resolution images of these neurons and their synapses. Finally, they tapped AI-powered algorithms to reconstruct the neural circuits and analyze structural changes at both the cellular and subcellular levels.

This multi-layered approach has opened new windows into the brain’s inner workings, offering an unprecedented level of detail and precision. It’s a model of how modern neuroscience is moving beyond snapshots of brain activity and into the realm of dynamic, structural understanding.

What’s Next? Unanswered Questions and Future Directions

This study raises as many questions as it answers. While the findings provide a detailed snapshot of memory-related changes in the hippocampus shortly after learning, they leave open the question of how these processes play out over time. What happens as memories are consolidated for long-term storage? Are multi-synaptic boutons a temporary feature, or do they persist as part of the brain’s long-term wiring?

Additionally, while this study focused on excitatory neurons in the hippocampus, memory formation likely involves a broader cast of characters. How do inhibitory neurons fit into the picture? Do similar structural mechanisms exist in other brain regions, such as the amygdala or cortex, which are involved in emotional memories and decision-making?

Finally, scientists want to know more about the molecular composition and behavior of multi-synaptic boutons. Could targeting these structures offer new avenues for treating memory-related disorders, such as Alzheimer’s disease or PTSD? Understanding the rules that govern their formation and maintenance may unlock new strategies for enhancing memory and learning.

Why It Matters: Beyond the Lab and Into Our Lives

Memory isn’t just a curiosity of brain science—it’s central to who we are. Every skill we learn, every experience we cherish, and every piece of knowledge we gather depends on the brain’s ability to store and retrieve information.

By uncovering the fine-grained architecture of memory formation, this research takes us a step closer to understanding—and potentially addressing—what goes wrong when memory fails. Disorders such as dementia, traumatic brain injury, and age-related cognitive decline could all be better treated with therapies rooted in this new understanding of how memories are made and maintained.

Moreover, these findings may eventually inform artificial intelligence. By mimicking the brain’s flexible and distributed approach to information storage, future AI systems could become more adaptive and resilient.

Reference: Marco Uytiepo et al, Synaptic architecture of a memory engram in the mouse hippocampus., Science (2025). DOI: 10.1126/science.ado8316. www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.ado8316

Think this is important? Spread the knowledge! Share now.