The ancient Egyptian colonial settlement of Tombos, located in Nubia, has long been regarded as an administrative and professional hub during the New Kingdom period (1400–650 BCE). Archaeologists initially theorized that its residents were minor officials, scribes, and craftspeople rather than laborers engaging in physically demanding work. However, a groundbreaking study has challenged these long-held assumptions, revealing a far more intricate labor system and social structure than previously believed.

Recent bioarchaeological research led by scholars from Leiden University, Purdue University, and the University of California at Santa Barbara has reassessed the physical activity levels of individuals buried at Tombos. Their findings, published in the Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, indicate that pyramid tombs—traditionally associated with elite status—housed not just high-ranking officials but also laborers who performed strenuous work. These revelations have significant implications for our understanding of social hierarchy, cultural identity, and labor organization in Egyptian-controlled Nubia.

Tombos: An Egyptian Colonial Stronghold in Nubia

Tombos was strategically established as an imperial outpost to secure Egyptian dominance over Nubia, a region rich in gold and other valuable resources. As a key administrative and military settlement, it was thought to have been primarily inhabited by Egyptian officials and their families, with labor primarily relegated to enslaved or lower-class Nubians.

Previous excavations suggested that the physical workload at Tombos was relatively light, reinforcing the notion that the settlement’s inhabitants were predominantly scribes, professionals, and minor officials rather than manual laborers. However, as excavation methods improved and bioarchaeological analyses expanded, a more nuanced picture of daily life at Tombos began to emerge.

New Skeletal Evidence Reveals a Complex Labor Structure

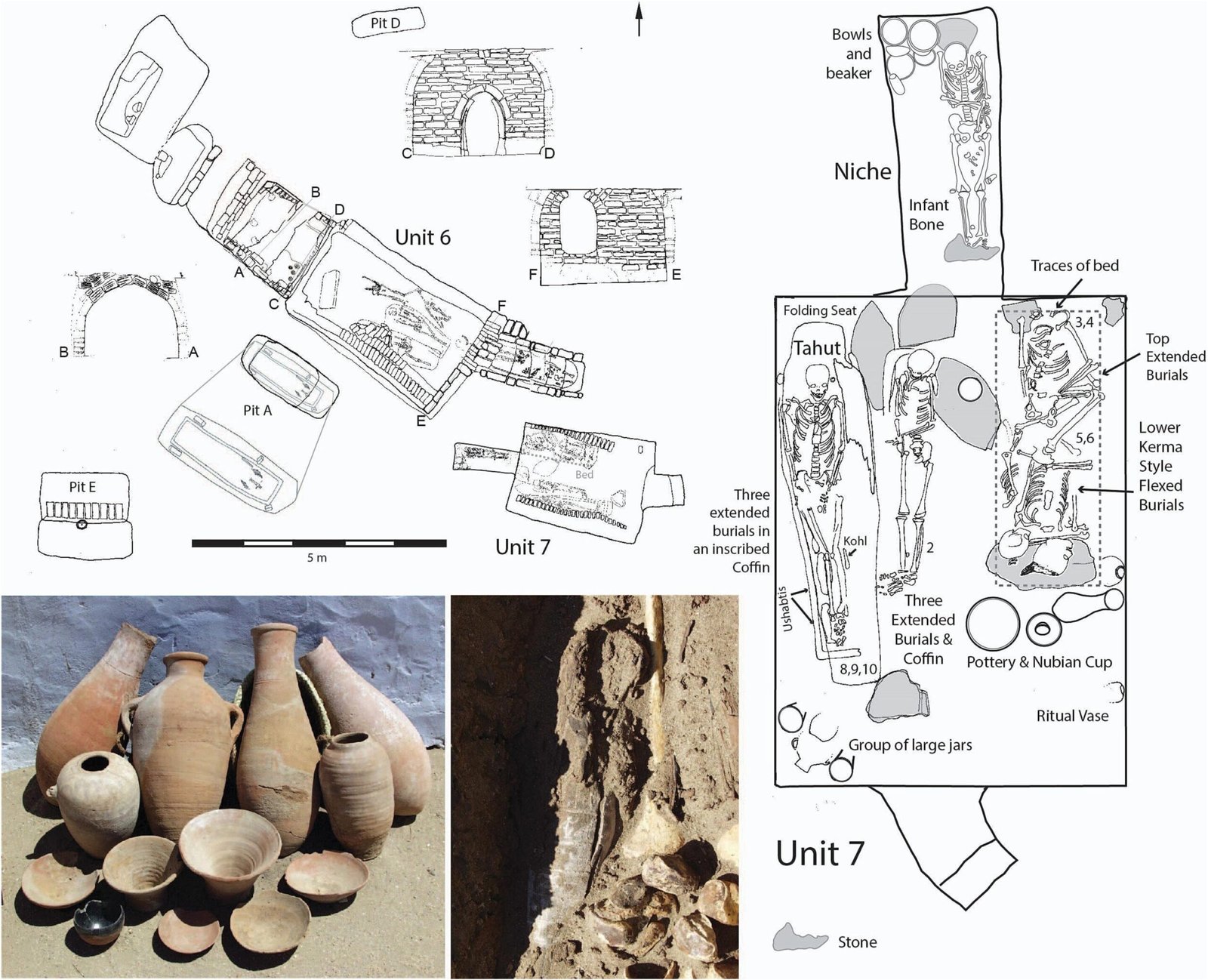

The study reexamined skeletal remains from three distinct cemetery areas at Tombos—the Western, Northern, and Eastern cemeteries—and analyzed the physical stress markers on these remains to assess labor intensity. Researchers focused on entheses (sites where muscles and ligaments attach to bones), which develop visible modifications when individuals engage in repetitive or strenuous activities over their lifetimes.

A cohort of 110 individuals was selected for analysis, with each skeleton’s 17 fibrocartilaginous entheseal sites assessed using a standardized six-point scale. The results were striking:

- Higher entheseal scores were found in individuals buried in Egyptian-style pyramid and chapel tombs, suggesting that they had engaged in physically demanding labor.

- Individuals in chamber tombs displayed moderate entheseal scores, aligning with earlier interpretations that middle-class professionals, such as scribes and craftsmen, were interred in these structures.

- Nubian-style tumulus burials showed generally lower entheseal scores, indicating reduced physical exertion among these individuals.

These findings challenge the long-held assumption that only elites were buried in monumental pyramid tombs. Instead, the data suggest that pyramid burials included a mix of elite administrators and laborers, possibly household staff or workers attached to high-status families.

Cultural Identity and Labor Roles in Colonial Nubia

Burial traditions at Tombos reflect a complex interplay between Egyptian and Nubian cultural practices. The study revealed that:

- Egyptian-style extended burials were dominant among those interred in pyramid tombs.

- Nubian-style flexed burials were more common in tumulus graves.

Interestingly, despite the physical differences in burial styles, there was no strong correlation between Nubian identity and increased physical labor. This contradicts previous theories that suggested Nubians in Egyptian-controlled settlements were primarily laborers serving the colonial administration. Instead, some local Nubians held social roles that did not require significant manual labor, possibly acting as intermediaries between Egyptian rulers and the native population.

Moreover, strontium isotope analysis was used to determine whether individuals were native to Tombos or had migrated from elsewhere. The results showed no significant differences in activity levels between locals and migrants, further suggesting that labor roles were not strictly dictated by geographic origin.

Monumental Burials: More Than Just Elite Tombs

One of the most striking revelations of this study is the reinterpretation of pyramid tombs. Traditionally, such structures were seen as reserved exclusively for high-ranking officials and elites. However, the presence of individuals with heavily developed entheseal markers in these tombs suggests that physically demanding labor was not a barrier to receiving a high-status burial.

This could indicate that:

- Some lower-status workers were interred alongside elites, possibly due to their close affiliations with noble families or administrative figures.

- Pyramid tombs may have been reused over multiple generations, leading to a mix of different social classes being buried together.

- Monumental burials could have been a status marker granted to particularly valued workers, such as skilled artisans or long-serving household staff.

This challenges the conventional binary view of ancient Egyptian society, where elites and laborers were assumed to have been rigidly separated in life and death. Instead, Tombos appears to have been a more fluid and socially diverse settlement than previously thought.

Women’s Roles in Colonial Society: A Social Broker Theory

Another key insight from this study involves the roles of local Nubian women in the colonial town. Low entheseal scores in some local women buried in flexed (Nubian-style) positions suggest they were not primarily laborers. Instead, researchers propose an alternative social function:

- Rather than being forced laborers, these women may have played intermediary roles in bridging Egyptian and Nubian communities.

- Some may have married Egyptian officials, facilitating cultural and social integration rather than simply being subjugated workers.

- Their presence in Nubian-style burials, despite low evidence of physical strain, suggests a more complex role in colonial dynamics, perhaps as wives, traders, or diplomats rather than manual laborers.

This discovery underscores the importance of women in colonial interactions, hinting that Egyptian-Nubian relations were more dynamic and reciprocal than previously assumed.

A New Perspective on New Kingdom Colonialism

The study’s findings reshape our understanding of Egyptian colonial settlements. Far from being elite enclaves with strictly separated social classes, New Kingdom towns like Tombos appear to have been more socially diverse, with laborers and elite officials potentially buried in the same monumental tombs.

Additionally, the research highlights:

- The importance of physical anthropology in revising historical interpretations.

- The fluidity of social status, where labor-intensive individuals could receive high-status burials.

- The role of women in cross-cultural exchanges within the Egyptian empire.

By integrating bioarchaeology, isotope analysis, and burial archaeology, researchers have challenged outdated models of Egyptian colonial rule, revealing a more nuanced picture of labor, identity, and social hierarchy.

Conclusion: Rethinking Ancient Labor and Status

The skeletal evidence from Tombos complicates the traditional narrative of New Kingdom colonial society. Instead of a rigidly stratified system where elites and laborers were clearly divided, the findings suggest a more integrated and fluid social structure, where:

- Some physically demanding labor roles did not preclude high-status burial.

- Nubian identity did not necessarily equate to hard labor or subjugation.

- Women may have served as cultural brokers rather than exploited workers.

This research underscores the importance of bioarchaeology in uncovering the lived experiences of ancient peoples, challenging previous assumptions about labor and status in Egyptian-controlled Nubia. The settlement of Tombos, once thought to be a bureaucratic outpost, now emerges as a socially diverse and dynamic community, reflecting the complex realities of Egyptian colonial rule in Nubia.

Reference: Sarah Schrader et al, Daily life in a New Kingdom fortress town in Nubia: A reexamination of physical activity at Tombos, Journal of Anthropological Archaeology (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.jaa.2025.101668