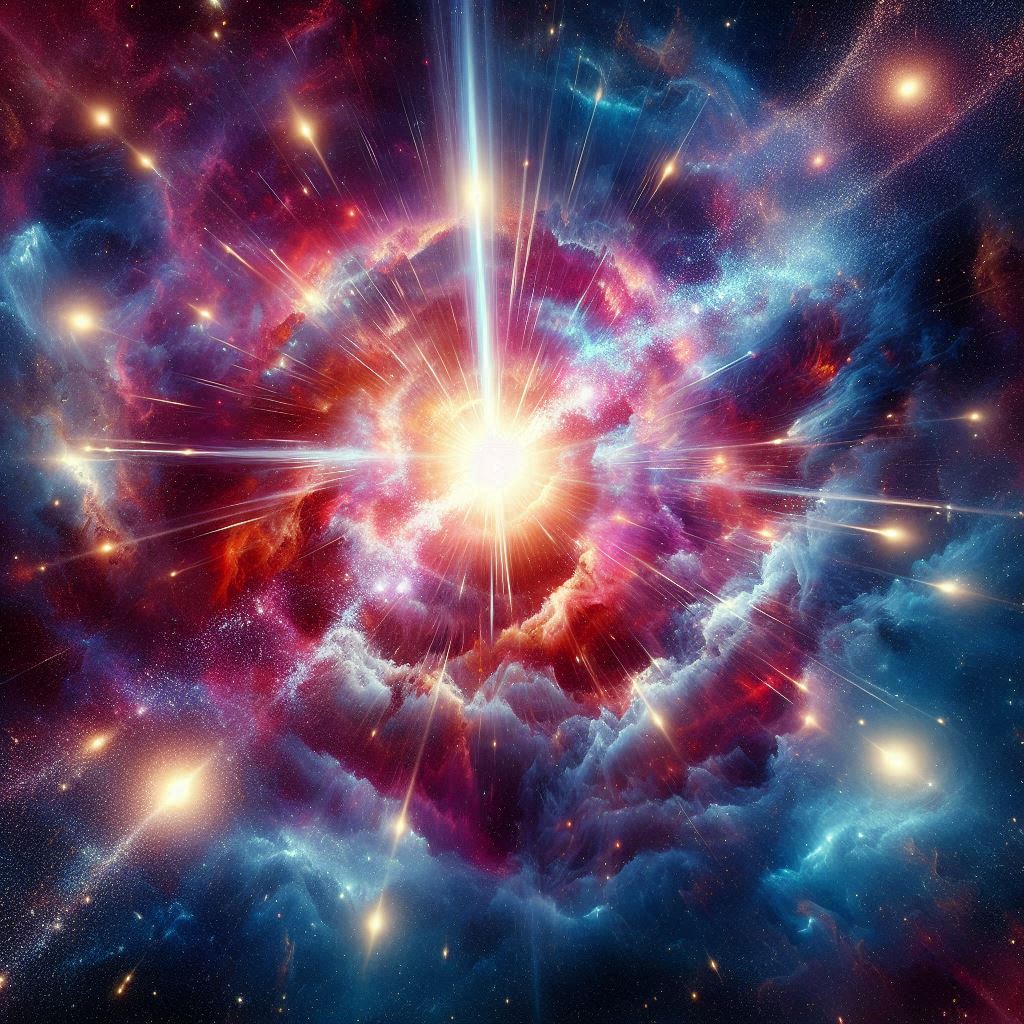

Picture the immense stillness of space—a cold, vast canvas of emptiness punctuated by brilliant, burning stars. These colossal objects seem eternal and immovable, the unshakable pillars of the universe. But what if they’re not? What if, instead of sitting serenely in the void, some stars are wracked by violent tremors, shaking and quivering with a force that defies human comprehension?

These stellar shudders are known as starquakes—the cosmic equivalent of earthquakes, but on an unimaginable scale. While our planet quakes due to shifting tectonic plates, starquakes ripple through the crusts of stars, releasing energy that can momentarily outshine entire galaxies. They can change the rotation of a star in an instant, send out bursts of deadly radiation, and even alter our understanding of space and time.

In this journey across the universe, we’ll explore what starquakes are, why they happen, and how they offer us profound insights into the life and death of stars. Prepare to dive into a cosmic phenomenon that’s as terrifying as it is fascinating.

Earthquakes vs. Starquakes – Similar Names, Wildly Different Realities

When the ground shakes beneath our feet, we call it an earthquake. The mechanics are relatively well understood: Earth’s lithosphere, divided into plates, floats atop a layer of molten rock. As these plates grind, collide, and slip past one another, stress builds until it’s suddenly released in a violent jolt, sending seismic waves through the ground.

But stars? They have no tectonic plates. They are gigantic balls of gas and plasma—aren’t they?

Not exactly. Some stars, especially a specific type known as neutron stars, do have something akin to a solid crust. And it’s on or beneath this crust where things get interesting—where tension builds up and is unleashed in an event we call a starquake.

Despite the similarities in the names, the scale and consequences of starquakes are almost impossible to grasp. An earthquake may unleash energy equivalent to a few atomic bombs. A starquake, on the other hand, can release energy equivalent to billions of nuclear bombs going off at once. Sometimes, that’s just the beginning.

The Stars That Shake – Neutron Stars and Magnetars

Not every star experiences quakes. The ones that do are a very specific breed: neutron stars and their more extreme cousins, magnetars.

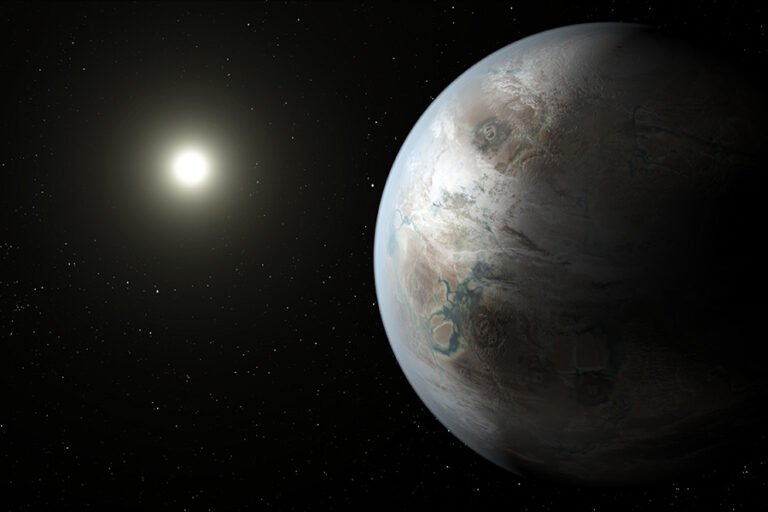

Neutron Stars – The Cosmic Corpses

Neutron stars are the remnants of massive stars that have exploded in a supernova. What’s left behind is an object so dense it defies logic. Picture this: A star once many times larger than the Sun has collapsed into an object only about 20 kilometers (12 miles) across—but it still contains more mass than the Sun. A single teaspoon of neutron star matter would weigh around a billion tons on Earth. That’s heavier than all the cars, buildings, and mountains on our planet combined.

This extreme density creates conditions that are ripe for starquakes.

Magnetars – Neutron Stars on Steroids

Among neutron stars, magnetars are the ultimate heavyweights. They have the strongest magnetic fields known in the universe—up to a thousand trillion times stronger than Earth’s. These magnetic fields are so powerful that they can distort the shape of the star, twist its crust, and create incredible stresses.

If neutron stars are like steel spheres, magnetars are steel spheres wrapped in tangled bands of titanic magnetic energy. The stresses in a magnetar’s crust are so intense that they periodically snap—resulting in a starquake.

What Causes a Starquake? The Tectonics of a Star

So how does a star “quake”?

The Crust of a Neutron Star

Despite being born in fire and fury, neutron stars develop a solid crust as they cool. This crust isn’t rock; it’s a layer of iron and exotic, neutron-rich nuclei, arranged in a rigid lattice. Think of it as an iron shell sitting atop a sea of incredibly dense nuclear matter. This crust, though strong, is under constant stress.

Stress Builds

Several forces can cause stress to build in this crust:

- Rotation Slowdown: Neutron stars spin extremely fast when they are first born—hundreds of times per second! Over time, they lose energy, and their rotation slows down. But as they slow, their shape wants to shift from an oblate spheroid (flattened at the poles) to a more spherical shape. This adjustment isn’t always smooth. Stress builds up in the crust as it resists the change, until—snap!

- Magnetic Field Twisting: In magnetars, it’s the intense magnetic field that creates stress. Twisting and shifting magnetic fields apply forces on the crust that can crack it apart like the shell of an egg squeezed in a vice.

- Glitches: Sometimes, neutron stars suddenly speed up, seemingly out of nowhere. These events, called glitches, are thought to be linked to sudden shifts in the crust or interactions between the crust and the superfluid interior of the star. A glitch can be caused by a starquake, and in turn, cause one.

The Snap!

When the stress in the crust becomes too great, it fractures. A starquake occurs. The crust shifts, releasing an enormous amount of energy in a tiny fraction of a second. The result can be a sudden spin-up (or slowdown) of the star’s rotation, bursts of high-energy X-rays and gamma rays, and even gravitational waves rippling through spacetime.

When Stars Quake – The Evidence We See

Starquakes aren’t just theoretical. We’ve observed their effects—though we didn’t always understand what we were seeing.

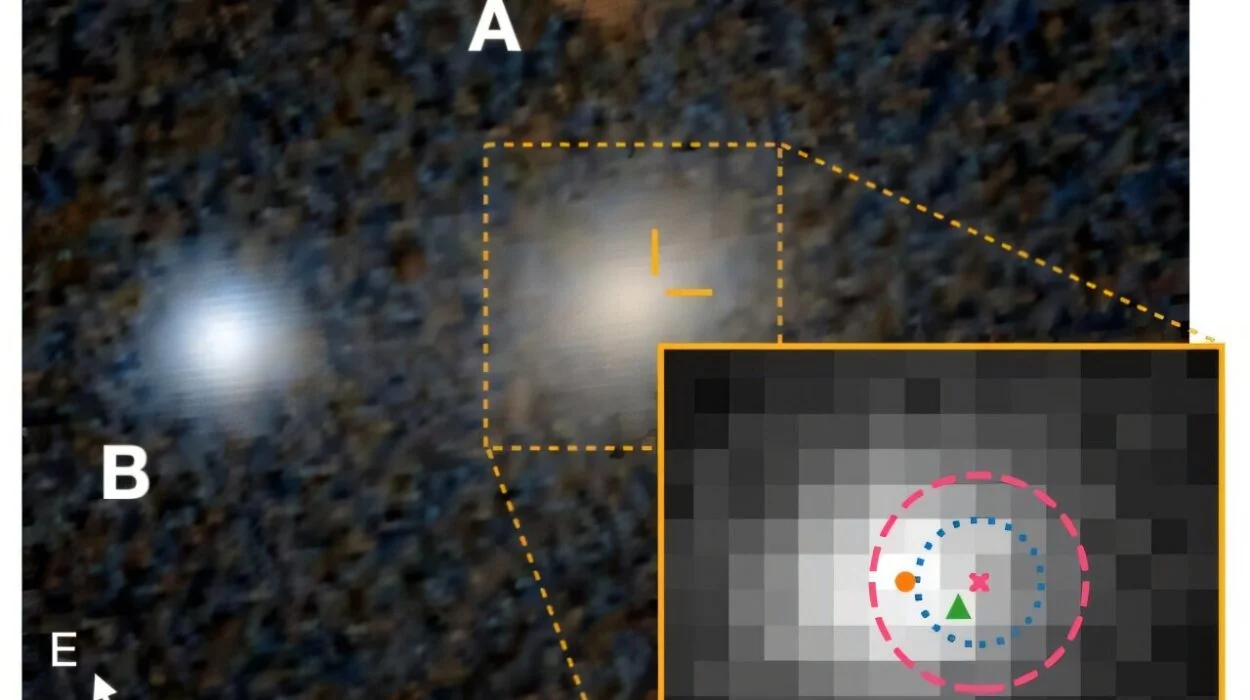

Soft Gamma Repeaters (SGRs) and Anomalous X-ray Pulsars (AXPs)

These are neutron stars (usually magnetars) that suddenly emit bursts of high-energy radiation—sometimes brief flashes, sometimes colossal explosions. In many cases, these bursts are thought to be the result of starquakes, as the crust snaps and rearranges itself.

The 1979 March 5 Event

On March 5, 1979, a burst of gamma rays swept over the Earth, setting off detectors on satellites designed to monitor nuclear explosions. For a few seconds, the burst was so intense that it overloaded sensors. Scientists traced it back to a magnetar in the Large Magellanic Cloud, about 50,000 light-years away.

The energy released in that single event was so immense that, if it had occurred within 10 light-years of Earth, it could have wiped out life on our planet. This event was later attributed to a massive starquake on the magnetar SGR 0525-66.

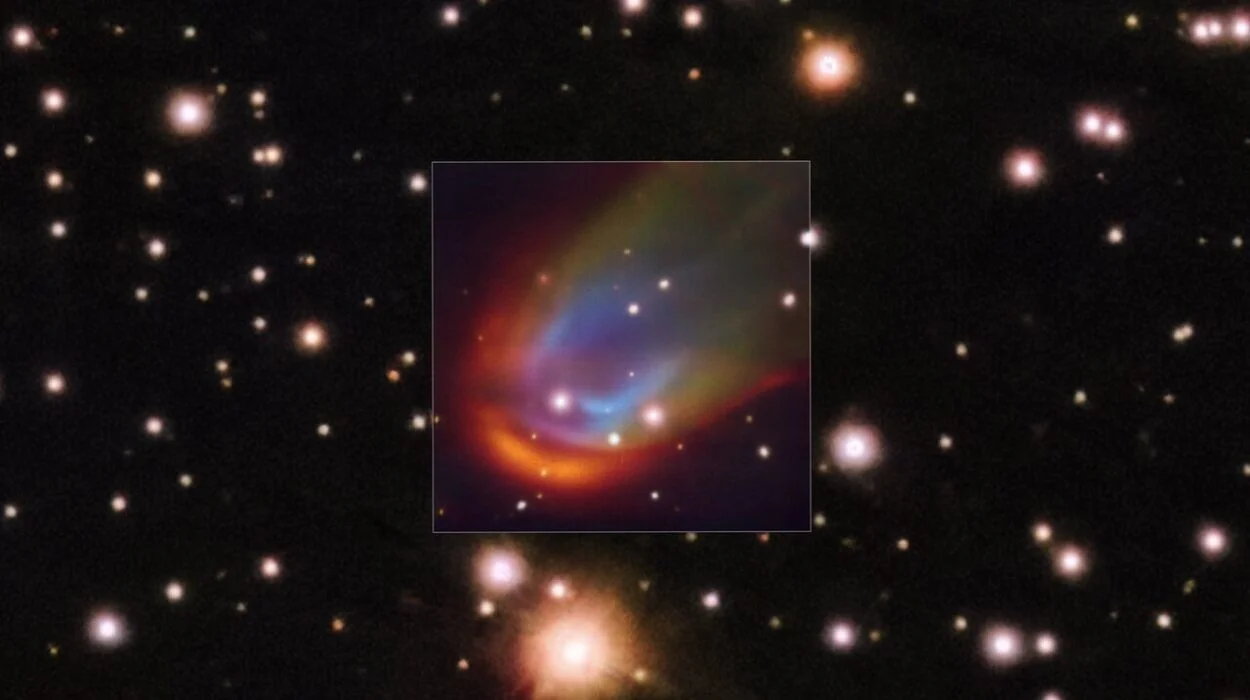

The 2004 Giant Flare

On December 27, 2004, a magnetar called SGR 1806-20 produced the most powerful gamma-ray flare ever recorded from outside our solar system. The starquake released more energy in a tenth of a second than the Sun emits in 150,000 years. The blast temporarily ionized Earth’s upper atmosphere and disrupted radio communications.

The Science Behind the Shaking – Seismology of Stars

Just like seismologists study earthquakes by analyzing seismic waves, astrophysicists study starquakes by looking at the oscillations they cause in neutron stars.

Quasi-Periodic Oscillations (QPOs)

After a starquake, the neutron star can ring like a bell. These vibrations are called quasi-periodic oscillations (QPOs). We can detect them in the X-ray and gamma-ray emissions following a giant flare. By analyzing these frequencies, scientists can probe the structure of neutron stars—learning about their crusts, magnetic fields, and even their cores.

It’s a kind of cosmic ultrasound, allowing us to “see” inside these dense objects in a way that’s otherwise impossible.

Starquakes and Gravitational Waves

One of the most exciting aspects of starquakes is their potential to produce gravitational waves—ripples in spacetime first predicted by Einstein.

When a massive starquake shifts the shape of a neutron star, it can send out gravitational waves. Though we haven’t definitively detected such waves from starquakes yet, future gravitational wave observatories like the upgraded LIGO, Virgo, and upcoming missions like LISA (Laser Interferometer Space Antenna) may catch them.

The detection of gravitational waves from a starquake would open up a new window into the behavior of matter under the most extreme conditions in the universe.

Could Starquakes Affect Earth?

The short answer: No, unless we’re very, very unlucky.

Neutron stars are generally far away from Earth. The closest known neutron star is about 400 light-years away—a safe distance. However, if a massive starquake occurred on a magnetar very close to Earth (within about 10 light-years), the gamma-ray radiation could be devastating.

Some scientists have speculated that past mass extinction events on Earth might have been triggered by gamma-ray bursts from distant magnetars, though this remains speculative.

Fortunately, the odds of a deadly starquake happening close enough to affect Earth are extremely low.

What Starquakes Teach Us About the Universe

Starquakes are more than just cosmic fireworks. They teach us about the fundamental physics of matter at nuclear densities. Understanding them helps us answer some of the biggest questions in astrophysics:

- What happens to matter when it’s squeezed beyond atomic limits?

- How do magnetic fields interact with matter at these densities?

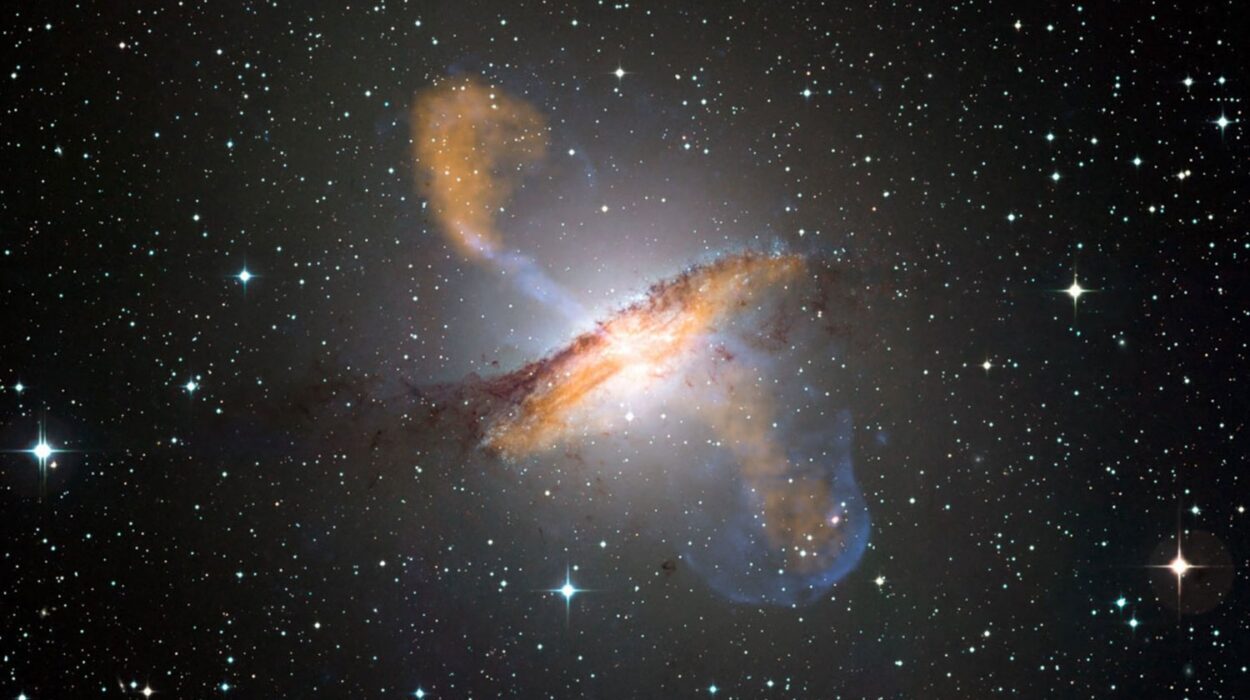

- What role do neutron stars and magnetars play in the evolution of galaxies?

Each tremor, each oscillation, and each burst of radiation brings us closer to unlocking these mysteries.

Conclusion: The Universe Trembles

We think of stars as symbols of stability—distant, eternal lights shining across cosmic time. But in reality, they can be restless, even violent. Starquakes are a powerful reminder of the dynamic, ever-changing nature of the universe.

When a neutron star’s crust cracks and its surface shudders, it’s a quake that shakes not just the star itself, but our understanding of the cosmos. Through these celestial shivers, we glimpse the secrets of gravity, magnetism, and nuclear physics. We peer into the hearts of stars, where matter is crushed to the breaking point.

And we are reminded, once again, of how small we are—and how vast and wondrous the universe remains.

Epilogue: The Next Quake

Somewhere out there, in a distant galaxy, a neutron star’s crust may already be under strain. Its magnetic fields are twisting tighter and tighter. Stress is building.

Soon, maybe tomorrow, maybe in a million years, it will snap.

And when it does, a star will quake—and we just might feel its tremors here on Earth, as faint whispers from a trembling universe.