A groundbreaking study recently revealed that the Turpan-Hami Basin in China’s Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region acted as a refugium, or a “life oasis,” for terrestrial plants during the end-Permian mass extinction, which occurred around 252 million years ago. This extinction event is widely regarded as the most catastrophic biological crisis since the Cambrian period, with over 80% of marine species wiped out. What’s even more significant is that this new research challenges the long-standing view that land ecosystems were equally devastated as marine environments during the end-Permian extinction.

The study, published in Science Advances, was led by Professor Liu Feng from the Nanjing Institute of Geology and Paleontology (NIGPAS) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. It provides the first conclusive fossil evidence that certain terrestrial ecosystems—specifically the plant communities in the South Taodonggou section—remained largely undisturbed during the end-Permian extinction event. This suggests that pockets of resilience existed on land, creating areas where life could not only survive but also continue to evolve in the aftermath of the crisis. This discovery has profound implications for our understanding of ecological resilience and recovery.

New Insights into the End-Permian Extinction

The end-Permian mass extinction, often referred to as the “Great Dying,” led to the collapse of ecosystems worldwide. While it is well-documented that marine life was decimated during this period, the impact on terrestrial ecosystems has been less clear. One prevailing theory is that the extinction was triggered by catastrophic volcanic eruptions in Siberia, which released vast amounts of greenhouse gases, causing global warming, acid rain, wildfires, and toxic gases. This theory suggests that these environmental changes led to widespread devastation, including the destruction of the characteristic plant species like Gigantopteris in South China and Glossopteris in Gondwanaland.

However, some researchers have argued that the effects of these volcanic events were not as widespread or uniformly destructive as previously thought. Instead, they contend that the impact of the extinction was influenced by latitude and atmospheric circulation, meaning that some regions may have been shielded from the worst effects. Fossil evidence from certain locations even points to the existence of Mesozoic plants that appear to have survived the extinction event, suggesting that life in these areas evolved without interruption.

The research team, led by Professor Liu, found compelling evidence that certain regions, including the Turpan-Hami Basin, were less affected by the extinction and served as refugia where life could persist and recover more rapidly. This new finding is a significant departure from the traditional narrative that all terrestrial ecosystems were uniformly decimated by the end-Permian event.

The Discovery of South Taodonggou

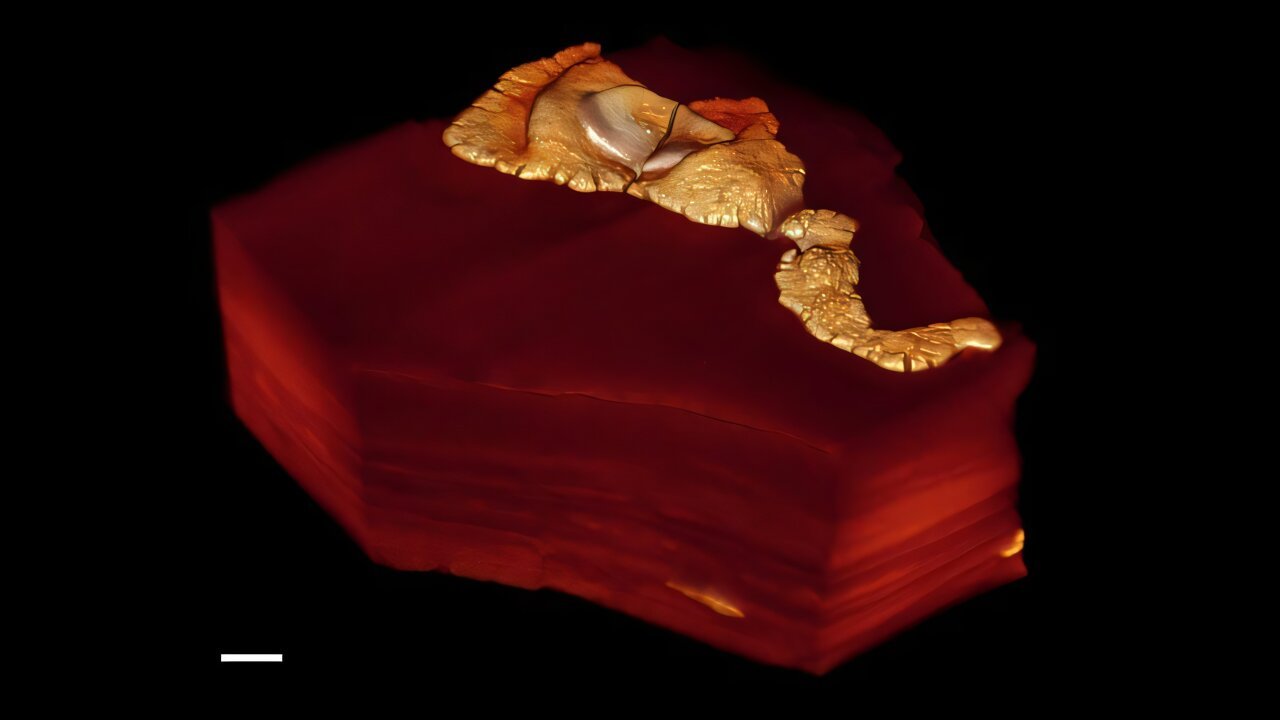

The key to this groundbreaking discovery lies in the fossil record preserved in the South Taodonggou section of the Turpan-Hami Basin. Detailed analysis of fossilized pollen, spores, and other plant remains, combined with precise dating techniques, revealed a continuous record of plant life that spanned from 160,000 years before the extinction event to 160,000 years after it ended. This research provides an uninterrupted timeline of plant communities thriving during a period that has been traditionally associated with widespread devastation.

Fossil evidence from the site indicates that riparian fern fields and coniferous forests flourished in this region even as the extinction event unfolded. The presence of intact tree trunks and fern stems, according to Professor Wan Mingli of NIGPAS, confirmed that these plants were part of the local vegetation, not just transported remnants from elsewhere. This is important because it suggests that the ecosystem in the Turpan-Hami Basin was relatively stable, providing a sanctuary for life during a time of global crisis.

Although some plant species disappeared locally, the extinction rate of spore and pollen species in the South Taodonggou section was far lower than what was observed in marine environments. The researchers estimate that only about 21% of the local spore and pollen species went extinct, a stark contrast to the over 80% loss of marine life. Moreover, the study found that many species previously thought to be extinct were later discovered in the Early Triassic strata elsewhere, suggesting that these species had simply migrated temporarily rather than becoming extinct.

A Rapid Ecological Recovery

One of the most remarkable aspects of this discovery is the speed with which the local ecosystem rebounded after the extinction event. Fossil evidence shows that within just 75,000 years after the extinction ended, the region supported a diverse range of tetrapods, including herbivorous species like Lystrosaurus and carnivorous species like chroniosuchians. This rapid recovery challenges the previous understanding that ecosystem recovery from the end-Permian extinction took millions of years. Instead, it suggests that some regions, such as the Turpan-Hami Basin, were able to recover much more quickly—more than ten times faster than other areas—due to their stable and relatively undisturbed ecosystems.

Professor Liu and his colleagues believe that the key to this rapid recovery was the region’s stable, semi-humid climate. Analysis of paleosol (ancient soil) matrices revealed that the South Taodonggou section received around 1,000 mm of rainfall annually during this period. This consistent rainfall provided abundant vegetation and a more habitable environment compared to other regions, which likely suffered more from the environmental stresses triggered by the volcanic activity associated with the end-Permian extinction. The favorable conditions in the Turpan-Hami Basin allowed for the survival and migration of terrestrial animals, which could feed on the abundant vegetation and contribute to the regeneration of the local food web.

A Safe Haven Amid Volcanic Chaos

Despite the close proximity of the Turpan-Hami Basin to the volcanic activity thought to have triggered the end-Permian extinction, the region appears to have served as a safe haven for terrestrial life. This discovery suggests that local climate and geographic factors can create surprising pockets of resilience, allowing life to persist even in regions that may seem inhospitable at first glance.

The study’s findings are not just significant for understanding ancient extinction events—they also carry important lessons for modern conservation efforts. In the face of ongoing threats like climate change and habitat destruction, identifying and protecting such refugia could play a critical role in preserving biodiversity and ensuring the resilience of ecosystems.

As Professor Liu Feng pointed out, “This suggests that local climate and geographic factors can create surprising pockets of resilience, offering hope for conservation efforts in the face of global environmental change.” In light of current concerns about a potential sixth mass extinction, driven by human activity, the discovery of the Turpan-Hami Basin as a “life oasis” highlights the importance of preserving ecosystems that may serve as refuges for biodiversity in times of crisis.

Implications for Modern-Day Conservation

The findings of this study resonate strongly in the context of current environmental challenges. With the ongoing decline in biodiversity, many scientists fear that we are on the brink of another mass extinction, one that could rival the end-Permian event in its scale and severity. The lessons drawn from the Turpan-Hami Basin offer hope that, with careful management and conservation efforts, certain ecosystems might be able to withstand the pressures of global environmental change.

In particular, the concept of refugia—areas that provide sanctuary for species during periods of ecological stress—could be critical for ensuring that vulnerable species have a chance to survive in the face of climate change. By identifying areas with stable climates, abundant resources, and minimal human interference, conservationists can create safe zones for species to thrive.

The research from the Turpan-Hami Basin shows that the resilience of ecosystems is often determined by a combination of local climate, geography, and the ability of species to migrate and adapt. These factors can create “oases” of life that persist even during times of global upheaval. Understanding and protecting such areas could be essential for ensuring the survival of biodiversity in the future.

Conclusion

The discovery of the Turpan-Hami Basin as a refugium during the end-Permian extinction provides a fresh perspective on the resilience of terrestrial ecosystems during one of the most catastrophic events in Earth’s history. This “life oasis” offers valuable insights into how local climate and geographic factors can protect biodiversity during times of global environmental crisis. The rapid recovery of ecosystems in the region underscores the importance of preserving such refugia, not only for understanding the past but also for securing the future of life on Earth. The study highlights the potential for natural resilience in the face of mass extinction, offering hope and guidance for modern conservation efforts.

Reference: Huiping Peng et al, Refugium amidst ruins: unearthing the lost flora that escaped the end-Permian mass extinction, Science Advances (2025). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.ads5614. www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.ads5614