The efficient architecture of our joints, which grants our skeletons both flexibility and durability, traces its origins back to some of the most ancient jawed fish ancestors. A significant study published in the open-access journal PLOS Biology by Neelima Sharma from the University of Chicago and her research team sheds new light on the evolutionary origins of synovial joints, a pivotal feature of the vertebrate skeleton. Their research reveals that the structural development of synovial joints began long before land vertebrates walked the Earth, originating in the ancestors of jawed vertebrates.

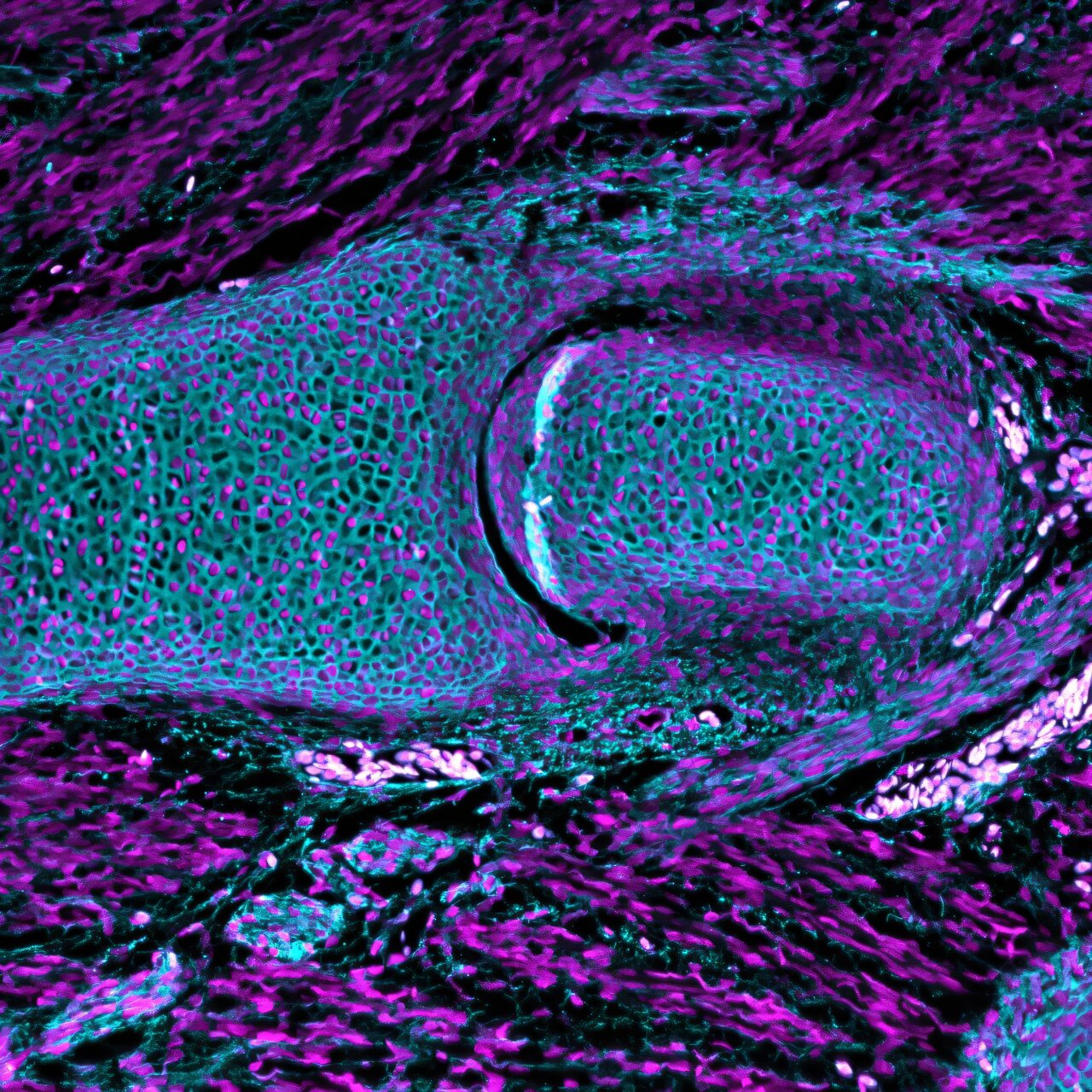

Synovial joints, which are present in most vertebrates, including bony fish and land vertebrates, provide enhanced mobility and stability compared to other types of joints. These joints allow for smooth and efficient movement because they include a lubricated cavity that facilitates the sliding of bones or cartilage against each other. This characteristic enables a level of movement that is crucial for the agility and function of vertebrates, from the smallest fish to the most agile mammals, including humans.

The Origin of Synovial Joints

The study conducted by Sharma and her colleagues aimed to pinpoint when these flexible yet sturdy joints first appeared in vertebrate evolution. Given that synovial joints are present in both land vertebrates and bony fish, researchers suspected that these joints may have evolved in a common ancestor of these groups. However, the exact timing and mechanism behind the appearance of these joints had remained unclear.

To investigate this, the researchers focused on three distinct vertebrate lineages: the jawless fish, particularly the sea lamprey, and two species of cartilaginous fish: bamboo sharks and little skates. These species were chosen because they represent early-branching vertebrate lineages, providing a closer glimpse into the ancestral origins of synovial joints.

Discoveries in Cartilaginous Fish and Lampreys

The team’s findings were illuminating. Cartilaginous fish, like the bamboo sharks and little skates, exhibited cavitated joints, which are joints that feature a lubricated space between two bones or pieces of cartilage, similar to the joints found in modern vertebrates. In contrast, the sea lampreys, as representatives of jawless fish, lacked this joint architecture, showing no cavitated joints in their anatomy.

Further investigation into the developmental processes of these fish revealed that the cartilaginous fish shared proteins and developmental pathways with the synovial joints of other vertebrates, including humans. These findings suggest a deeper evolutionary connection between these species and modern vertebrates, indicating that the ability to form synovial joints was likely present in their common ancestors.

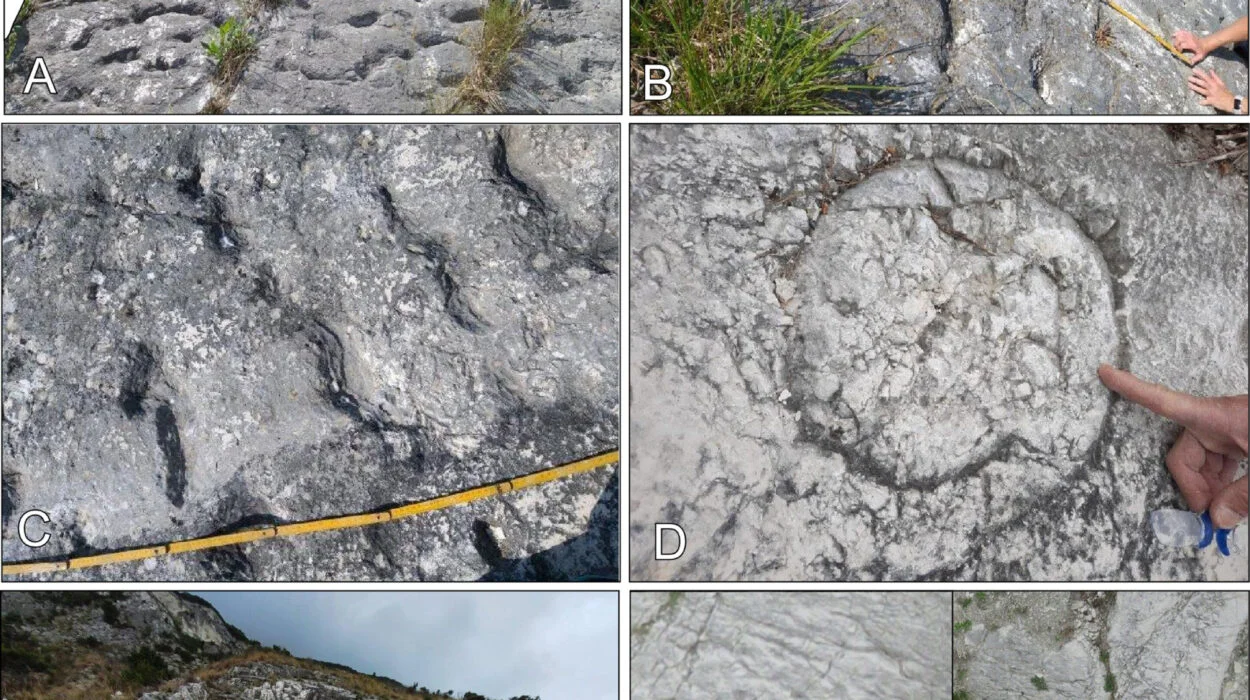

CT Scans Reveal Early Synovial Joints in Fossil Fish

In addition to examining living species, the team also turned to fossil evidence to uncover the evolutionary history of synovial joints. Using CT scans, they analyzed the anatomy of fossil fish, specifically Bothriolepis, one of the earliest known species of jawed fish. The analysis revealed a similar cavitated joint structure, providing direct evidence of the presence of synovial joints in a species that existed hundreds of millions of years ago. This fossil evidence solidified the conclusion that synovial joints first evolved in jawed vertebrates, predating the emergence of land vertebrates.

Implications for Vertebrate Evolution

This study provides crucial insights into the origins of vertebrate skeletal architecture, particularly how the evolution of mobile joints shaped the way vertebrates moved, fed, and interacted with their environments. The development of synovial joints allowed for more dynamic movement, making it possible for vertebrates to explore a wider range of behaviors, such as hunting, escaping predators, and adapting to new habitats. In essence, the ability to create mobile joints opened up new ecological niches and set the stage for the diverse range of vertebrate locomotion that we see today.

The study’s authors suggest that this evolutionary innovation was a key factor in the success of jawed vertebrates, allowing them to thrive and diversify into the many species we observe today, including humans. Understanding the deep evolutionary roots of synovial joints helps scientists better appreciate the complexity of vertebrate evolution and how seemingly simple biological features can have profound implications for an organism’s survival and adaptation.

Future Directions in Joint Evolution Research

The findings of this study are just the beginning. The authors propose that future research could focus on examining joint morphology in other fossil fish lineages to further explore how synovial joints evolved in different branches of the vertebrate family tree. Comparing the joint structures of jawed and jawless vertebrates could also reveal more details about how early vertebrate evolution shaped the structure and function of joints across different species.

In particular, studying the developmental processes that contribute to joint formation could provide more insight into how certain species developed the ability to create mobile, efficient joints, while others, like lampreys, retained more primitive joint structures. This research could shed light on how complex biological features evolve and become adapted to the specific needs and environments of various species.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study offers groundbreaking insights into the evolutionary origins of synovial joints in vertebrates. By examining the joint anatomy and development of early vertebrate species, Sharma and her colleagues have revealed that synovial joints likely first evolved in jawed vertebrates, such as ancient fish like the bamboo sharks, little skates, and Bothriolepis. These mobile joints would become one of the defining features of the vertebrate skeleton, enabling vertebrates to explore new ways of moving and interacting with their environments.

This research not only enhances our understanding of vertebrate evolution but also provides a foundation for further investigations into the origins of skeletal and joint development. As scientists continue to study the evolutionary history of joints, they will likely uncover even more fascinating details about the early origins of the vertebrate skeleton—a key factor in the success and adaptability of species ranging from ancient fish to modern humans.

Reference: Sharma N, et al. Synovial joints were present in the common ancestor of jawed fish but lacking in jawless fish. PLOS Biology (2025). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3002990