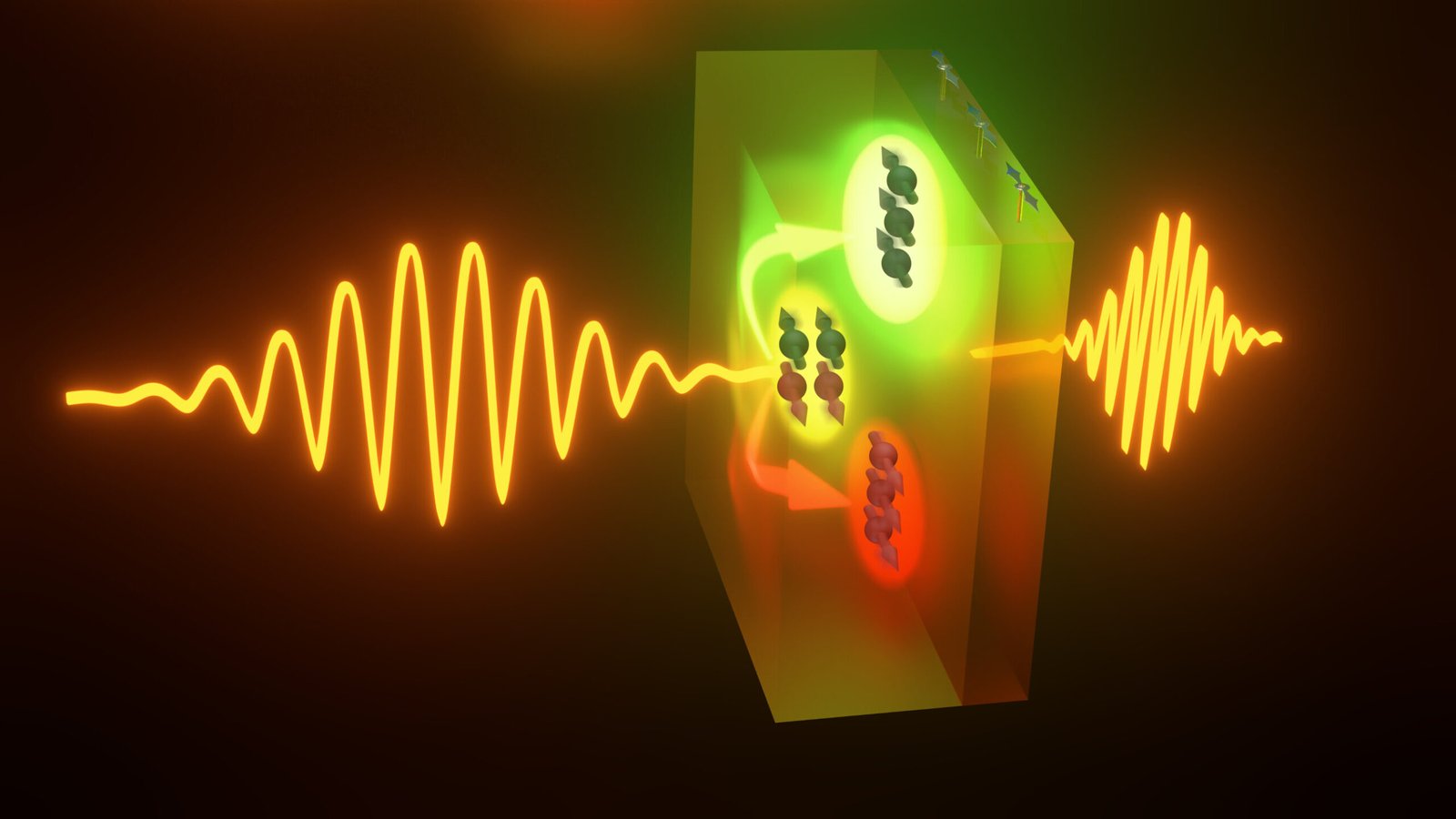

In a world where data speeds continue to grow increasingly important, traditional data storage methods are reaching their limits. Despite significant advancements in technology, data rates today only reach a few hundred megabytes per second, and improving these speeds remains a pressing challenge. However, a promising breakthrough could soon accelerate the rate at which we can access digital information—through the use of magnetic states read by ultrafast terahertz light pulses. Researchers at the Helmholtz-Zentrum Dresden-Rossendorf (HZDR) and TU Dortmund University are now showing the world just how this innovative approach could transform our understanding of ultrafast data sources.

Their recent work, published in Nature Communications, demonstrates that instead of relying on electrical pulses, terahertz light pulses can be used to read magnetic structures in a matter of picoseconds—trillions of a second. This research brings us one step closer to overcoming the previous speed limitations of data storage and opening the door to new generations of ultrafast memory systems.

From Electrical to Light-Induced Magnetic Read-Out

Dr. Jan-Christoph Deinert, a researcher at HZDR’s Institute of Radiation Physics, explains how this new method works: “We can now determine the magnetic orientation of a material much quicker with light-induced current pulses.” But what’s truly fascinating about this breakthrough is that the light pulses used are invisible to the human eye—terahertz radiation, which lies between infrared and microwave radiation on the electromagnetic spectrum. These terahertz pulses, with a wavelength just under a millimeter, hold immense potential to change the speed at which magnetic states can be read.

The researchers took advantage of the unique properties of terahertz light to examine and manipulate magnetic materials. Using the ELBE radiation source at HZDR, which generates extremely short and intense terahertz pulses, they were able to study and analyze wafer-thin magnetic materials in real time. This terahertz light proved ideal for reading the magnetization of material samples just nanometers thick.

Nanometer-Thin Layers for Ultrafast Magnetic Storage

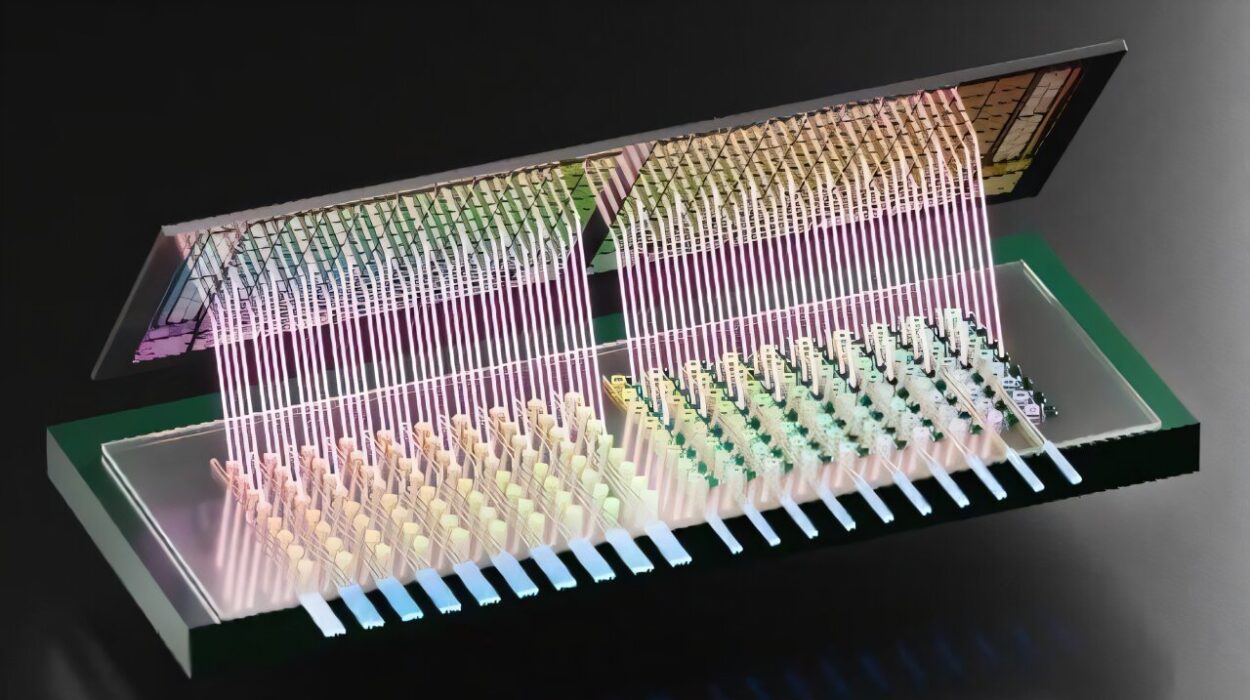

The key to making these terahertz pulses effective lies in the materials used for the samples. The team constructed thin film samples consisting of two layers. The lower layer was composed of magnetic materials, such as cobalt or iron-nickel alloys, while the upper layer was made from metals like platinum, tantalum, or tungsten. These metal layers were just three nanometers thick—roughly 1,000 times thinner than the width of a human hair. At such small scales, only part of the terahertz radiation is able to penetrate the material, which is essential for the experiment to work.

Dr. Deinert explains this concept further: “The material can only be penetrated by part of the terahertz radiation when the layers are this thin.” This partial transparency of the material allows researchers to read the magnetization of the lower magnetic layer, making the system a perfect candidate for studying ultrafast magnetic data storage.

A Simple Material, A Complex Mechanism

While the materials themselves are relatively simple, the mechanisms at play are anything but. Dr. Ruslan Salikhov, from HZDR’s Institute of Ion Beam Physics and Materials Research, explains the complexity of the interactions: “In our experiments, the terahertz flashes generate a variety of interactions between light and matter.” The research team utilized these interactions to study fast-moving relativistic quantum effects within the thin material layers.

The process begins with the terahertz pulses generating extremely short-lived electric currents in the upper metal layer. But these aren’t just any ordinary currents. The terahertz light induces the electrons to arrange themselves according to their intrinsic angular momentum—referred to as spin. The result is a spin current that flows perpendicular to the layers, setting the stage for the next step of the process.

At the interface between the two layers, the electrons with specific spin orientations accumulate in quick succession. The direction of these spins, along with the magnetization of the lower layer, alters the electrical resistance at the interface. This change in resistance is known as unidirectional spin Hall magnetoresistance (USMR), a phenomenon previously discovered by researchers at ETH Zurich.

What makes this breakthrough so remarkable is that USMR allows the researchers to rapidly detect the magnetization direction. The terahertz pulses interact with the spin current at such a high frequency—trillions of times per second—that they cause a corresponding change in the electrical resistance, which can be detected and used to determine the magnetization.

The Second Harmonic: A Key to Ultra-Fast Detection

The most fascinating part of the discovery lies in the way the terahertz pulses respond to changes in the magnetization. As Dr. Sergey Kovalev from TU Dortmund University describes it: “Depending on the direction of magnetization, we generate fast fluctuations in the transparency of the sample.” This fluctuation is critical because it alters the terahertz pulses in a specific manner. After passing through the material, the terahertz radiation oscillates at twice the frequency of the original pulse. This is referred to as the “second harmonic” frequency, and it serves as a clear marker of the magnetization direction.

By carefully measuring this second harmonic, the team was able to precisely determine the magnetization direction of the lower layer, all within a time frame of just a few picoseconds. This ultrafast measurement is a significant step forward in the quest to develop faster, more efficient data storage systems.

Writing Magnetic Data with Terahertz Radiation

While the primary focus of this research has been on reading magnetic data using terahertz pulses, the team is also exploring ways to write data to these ultrafast memory systems. Using terahertz radiation to not only read but also write information could enable the creation of ultrafast, high-capacity magnetic memory devices. However, the researchers acknowledge that translating this proof of concept into a fully functional system for writing and reading magnetic data will require further technological advancements.

For instance, more compact sources of terahertz pulses and more efficient sensors for detecting the terahertz radiation are essential for making this technology practical. The team recognizes that while the potential is huge, it will take considerable time and development before we see terahertz-driven ultrafast hard drives or memory devices in everyday use.

The Road Ahead: A Future of Ultrafast Magnetic Memory

The work conducted by the HZDR and TU Dortmund University team has opened a new chapter in the field of ultrafast magnetic memory. The use of terahertz pulses to read and possibly write data in picoseconds offers the potential for a dramatic leap in storage and computing speeds. While the technology is still in its early stages, the findings have already shown that even relatively simple material systems can hold the key to unlocking the next generation of ultrafast data storage devices.

As researchers continue to refine and optimize the technology, the possibilities are exciting. The day may not be far off when we have access to memory systems that operate at speeds previously thought impossible. These advances could revolutionize fields ranging from artificial intelligence to scientific simulations, where speed and data access are crucial.

In conclusion, the research into terahertz-based ultrafast magnetic memory provides an exciting glimpse into the future of data storage. By leveraging the unique properties of terahertz light and the complex interactions between light and magnetism, researchers are setting the stage for a new era of ultrafast memory that could one day be the backbone of next-generation computing technologies. While challenges remain, the progress made so far is both promising and inspiring, pushing the boundaries of what we thought possible in data storage and processing.

Reference: Ruslan Salikhov et al, Ultrafast unidirectional spin Hall magnetoresistance driven by terahertz light field, Nature Communications (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-57432-2