For centuries, humanity has gazed up at the night sky and wondered if we are alone. Among the distant stars, one world has sparked our imagination more than any other: Mars. The Red Planet has long been a symbol of both mystery and possibility. Its barren landscapes, massive canyons, and ancient riverbeds tell a story of a planet that was once wetter, maybe even warmer, than it is today. But now, Mars is a cold, desolate world, its thin atmosphere offering little protection from harsh solar radiation, its soil dry and toxic, its average temperatures colder than the most unforgiving places on Earth. And yet, it’s this very emptiness that invites the most daring human vision of all time: to terraform Mars—to make the Red Planet green.

Terraforming isn’t just science fiction anymore. As humanity stands on the cusp of becoming a multi-planetary species, the idea of reshaping an entire world to support life is shifting from dream to plan. This essay dives deep into the concept of terraforming Mars, exploring the science, the challenges, the ethics, and the future of making a red planet green.

Why Mars?

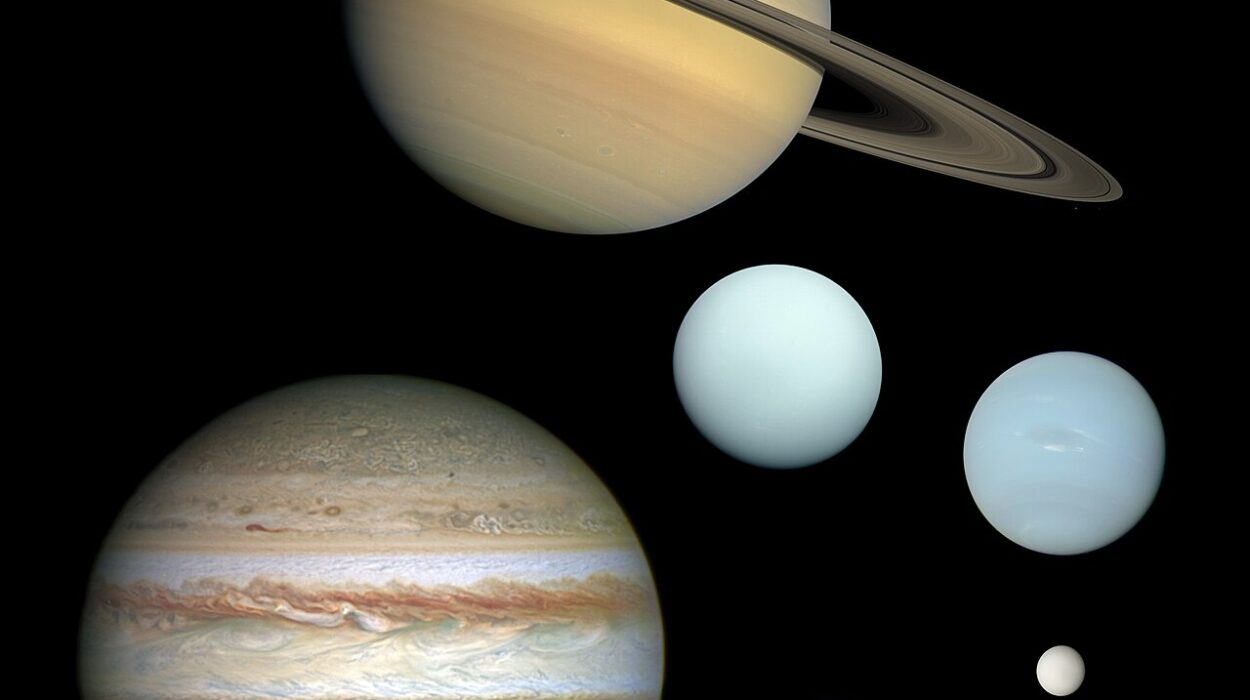

Before we dive into the how, let’s talk about the why. Of all the celestial bodies in our solar system, why does Mars stand out as the best candidate for terraforming?

Earth’s Little Brother

Mars is often called Earth’s little brother. Though it’s about half the size of Earth, many of its features are strikingly similar. It has seasons, polar ice caps, volcanoes, and canyons. A day on Mars—called a sol—is just over 24 hours. Unlike Venus, where surface temperatures are hot enough to melt lead and the atmospheric pressure is crushing, Mars is relatively tame. It’s cold, yes, but it’s manageable. The gravity is about 38% of Earth’s, enough that it could theoretically maintain a breathable atmosphere, if we could somehow provide one.

Historical Water and the Possibility of Life

Mars wasn’t always a frozen desert. Billions of years ago, it had rivers, lakes, and possibly even oceans. Evidence from rovers and orbiters suggests water once flowed freely on its surface. If life ever existed beyond Earth, Mars is one of the first places we might find it.

A Second Home for Humanity

With Earth’s future uncertain—thanks to climate change, overpopulation, and potential natural or human-made disasters—many believe it’s time we expanded our home. Mars offers a potential refuge, an insurance policy for humanity. If we could turn it into a habitable world, we wouldn’t just have a new frontier; we’d have a backup for our species.

What Does It Mean to Terraform?

Terraforming, as a term, was first coined by science fiction writer Jack Williamson in 1942. It refers to the process of transforming a planet’s environment to make it suitable for Earth-based life. In Mars’ case, it means thickening the atmosphere, warming the planet, and introducing oxygen and water. The end goal is a world where humans, plants, and animals can live and thrive without life-support systems.

But how would we do that? And could we? These are the questions scientists, futurists, and visionaries are working to answer.

Step 1: Warming Up the Planet

Mars is cold—very cold. The average temperature hovers around -80°F (-62°C). To make the surface warm enough for liquid water and plant life, we need to initiate global warming on a planetary scale. Ironically, the very thing threatening Earth’s climate could be the key to Mars’ salvation.

Greenhouse Gases: Mars Needs a Blanket

One proposed method is to release greenhouse gases into the Martian atmosphere. Carbon dioxide (CO₂), methane (CH₄), and other compounds could trap heat, creating a runaway greenhouse effect similar to what’s happening on Venus—but controlled.

The good news? Mars already has a lot of CO₂. The polar ice caps are made of frozen carbon dioxide. By heating these caps, we could release vast amounts of CO₂ into the air. How? We could use giant mirrors in space to reflect sunlight onto the poles, or we could deploy nuclear-powered heaters. As the CO₂ sublimates (turns from solid to gas), the atmosphere thickens, trapping more heat, and warming the planet further.

This would kick off a positive feedback loop: more heat releases more CO₂, which traps more heat, and so on.

Super Greenhouse Gases

Another idea is to manufacture super greenhouse gases—compounds that are thousands of times more effective than CO₂ at trapping heat. These perfluorocarbons (PFCs) are synthetic and don’t break down easily, making them perfect candidates for a long-lasting warming effect. Factories on Mars, run by robots or early settlers, could churn out these gases and pump them into the atmosphere.

Asteroid Bombardment: Planetary Engineering with a Bang

Another bold proposal: redirect asteroids or comets rich in ammonia (another greenhouse gas) to slam into Mars. The impacts would release heat and gas, both warming the planet and adding volatile compounds to the atmosphere. It sounds crazy, but on a cosmic scale, it’s not impossible. We’d just need the technology to safely redirect massive space rocks. No pressure.

Step 2: Thickening the Atmosphere

Once Mars is warm enough, we need to make its atmosphere thick enough to retain that heat and support human life. Right now, Mars’ atmosphere is less than 1% as dense as Earth’s. That’s why it can’t hold onto much heat and why the surface pressure is too low for liquid water to exist in most places.

Warming the planet would help sublimate CO₂ from the ground and the polar ice caps, thickening the atmosphere. But we might need more. One idea is to import gases from elsewhere, like ammonia from the outer solar system. Another option is to mine Martian rock for nitrogen and other gases, releasing them slowly over time.

The goal is to create a breathable mix of gases, or at least an atmosphere dense enough that pressure suits aren’t necessary. Oxygen would still need to be added in later stages, but a dense CO₂ atmosphere would be a good start for warming and plant growth.

Step 3: Liquid Water—Making It Flow Again

Mars has water ice—plenty of it. The polar ice caps and underground glaciers are loaded with frozen H₂O. Once the planet warms up, we could see these ice deposits melt, creating rivers, lakes, and possibly seas. Some scientists believe that with enough atmospheric pressure and heat, water could flow again across much of Mars’ surface.

We might also need to help things along. Building massive pipelines to distribute water, melting ice with heat sources, or even importing water from comets could be part of the process.

Water is life. Once it’s flowing, Mars becomes far more hospitable. Algae and bacteria could thrive in shallow pools and lakes, kickstarting an ecosystem that slowly builds toward complexity.

Step 4: Oxygen—Breathing New Life into Mars

Even if we have warmth, pressure, and water, humans can’t breathe CO₂. We need oxygen. Earth’s atmosphere is about 21% oxygen—Mars, almost zero. So how do we add O₂ to the mix?

Plants and Algae: Nature’s Oxygen Factories

The easiest, most Earth-like way is photosynthesis. Plants, algae, and cyanobacteria take in CO₂ and release O₂. Once Mars is warm enough, we could introduce hardy plant life to start converting CO₂ into oxygen. Specially engineered algae could colonize lakes and oceans, pumping out oxygen as they grow.

But this would take time—millennia, according to some estimates. Mars doesn’t have plate tectonics to recycle nutrients or a magnetic field to protect life from solar radiation, so progress could be slow.

Machines: Breathing Life with Technology

Alternatively, we could use machines to speed things up. MOXIE, an experiment on NASA’s Perseverance rover, is already testing how to extract oxygen from Mars’ CO₂-rich atmosphere. Scaling up this technology could mean vast factories producing O₂ for settlers and, eventually, for the atmosphere itself.

Step 5: Protecting Life—Radiation and Magnetic Fields

Even if we manage to create a thicker atmosphere, Mars lacks a global magnetic field. Earth’s magnetosphere shields us from harmful solar and cosmic radiation. Mars’ surface is bombarded by this radiation, which is dangerous for both humans and potential ecosystems.

Artificial Magnetospheres

One proposal is to create an artificial magnetosphere. We could place a massive magnetic shield at the Mars-Sun L1 Lagrange point, where gravitational forces would keep it steady. This shield would deflect solar wind and radiation, protecting Mars much like Earth’s magnetic field does.

Alternatively, we could create localized magnetic fields around colonies using superconducting magnets. These would protect specific areas rather than the entire planet.

The Timeline: How Long Would It Take?

Terraforming Mars wouldn’t be a quick process. Depending on the methods used, it could take centuries—or even millennia—to make Mars truly Earth-like. Warming the planet and thickening the atmosphere might take a few hundred years. Building oxygen levels high enough to support unprotected human life could take much longer.

But even partial terraforming could be useful. Creating habitable zones, domed cities, or greenhouses could allow human life to thrive while the larger process unfolds. Terraforming doesn’t have to be all-or-nothing; it can be incremental.

The Ethics of Terraforming: Should We Do It?

Even if we can terraform Mars, there’s a big question left: should we?

Protecting Potential Martian Life

If life exists—or once existed—on Mars, do we have the right to change its environment? Terraforming could wipe out native microbes or make it impossible to study Mars’ past in its natural state. Some argue that Mars has its own intrinsic value and that we should protect it rather than reshape it.

Humanity’s Stewardship of Worlds

On the other hand, some believe it’s humanity’s destiny to spread life beyond Earth. We are, after all, products of life itself. Terraforming Mars could be seen as extending Earth’s biosphere, bringing life to a dead world.

Lessons from Earth

Critics point out that we haven’t exactly done a stellar job managing our own planet. Climate change, pollution, and species extinction are all human-made problems. Do we have the wisdom to responsibly terraform another world?

These are questions with no easy answers. But they’re questions we must ask before taking the first steps toward planetary engineering.

The Technology: Are We Ready?

We’re not there yet—but we’re getting closer. NASA, SpaceX, and other organizations are developing the tools we’ll need to reach and settle Mars. SpaceX’s Starship is being designed to carry humans and cargo to Mars within the next few decades. MOXIE is a proof-of-concept for oxygen production. Advances in synthetic biology and genetic engineering could give us the hardy organisms we need to jumpstart ecosystems.

In the coming century, our capabilities will grow. What seems impossible today may become routine tomorrow.

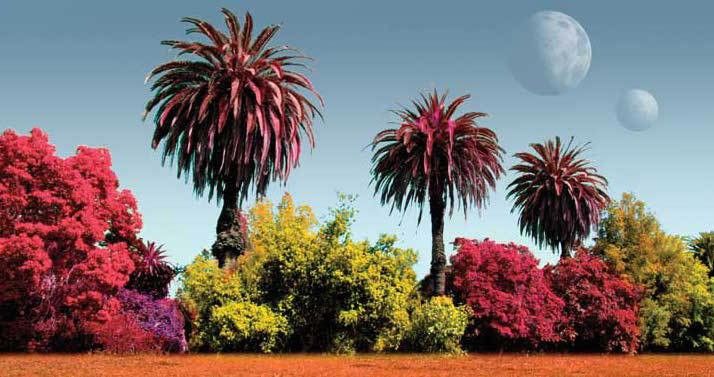

Visions of a Green Mars

Imagine standing on a terraformed Mars. The air is crisp but breathable. Grasses ripple in the wind. Trees line riverbanks, their roots drinking from clear, cold streams. Animals roam wide plains under a blue sky. Lakes reflect the sunrise. Humans live in towns and cities, their children growing up never knowing what it was like to live inside domes.

It’s a vision both fantastical and, perhaps, inevitable. As we look toward the stars, Mars is our first and greatest challenge. To terraform it is to rewrite the story of life itself—a story that began on Earth and may one day stretch across the cosmos.

Conclusion: Making the Red Planet Green

Terraforming Mars is one of humanity’s most audacious dreams. It’s a testament to our ingenuity, ambition, and hope. The journey will be long and filled with challenges, both scientific and ethical. But if we succeed, we won’t just make Mars habitable; we’ll take our first steps toward becoming an interplanetary species.

Making the Red Planet green isn’t just about changing a world—it’s about changing ourselves. It’s about rising to meet the challenges of the cosmos and claiming our place among the stars.

And who knows? Maybe one day, when our descendants walk through Martian forests and swim in Martian seas, they’ll look back at us—the dreamers—and be thankful we dared to begin.