Stress is an inescapable part of life. From the pressures of work to the challenges in relationships, it seems that no one can avoid the overwhelming sensations of anxiety, tension, and frustration that accompany stress. But while stress is a common experience, most people don’t fully understand what happens in the body when they feel overwhelmed.

We talk about feeling “stressed out” or being “on edge,” but how often do we consider the biological mechanisms at play when our body reacts in these ways? To truly understand why we snap or feel overwhelmed by stress, we need to take a journey into the inner workings of the human body, exploring how stress affects our brains, hormones, and even our physical health.

What is Stress, Really?

Before diving into the science, let’s first define stress. The term is often used to describe a wide array of physical, mental, and emotional responses that arise when we perceive a threat or challenge. Stress is essentially the body’s way of reacting to changes in the environment—whether those changes are real or imagined.

From an evolutionary perspective, stress was designed to help us survive. In the past, stressors were often physical dangers, such as encountering a predator or facing an immediate physical threat. Today, however, stressors are typically less physical and more mental: meeting deadlines, handling interpersonal conflicts, or dealing with financial worries. While the threats may have changed, the body’s response remains remarkably similar to the ancient “fight-or-flight” reaction.

The Stress Response: An Intricate Web of Signals

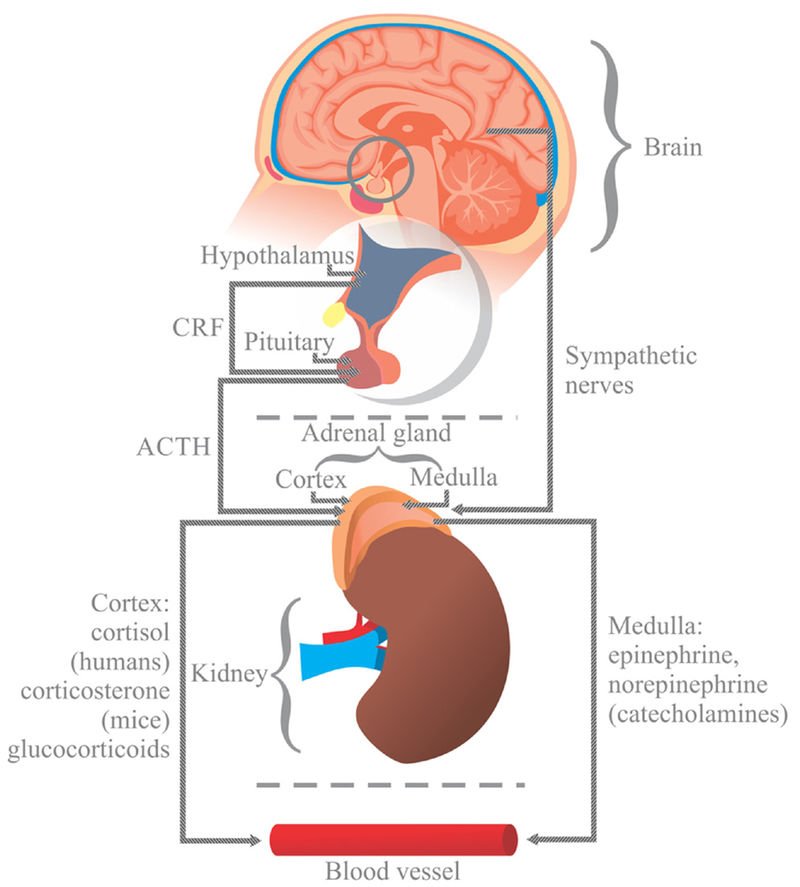

When stress occurs, it triggers a complex physiological response in the body. The main players in the stress response are the brain, the endocrine system, and the autonomic nervous system. Together, these systems work in harmony to prepare the body to either fight or flee from danger.

The Brain’s Role in Stress

At the heart of the stress response lies the brain, particularly a region known as the hypothalamus. When a stressful event is perceived, sensory information is sent to the brain, and the hypothalamus evaluates whether this information poses a threat. If the brain detects danger, the hypothalamus activates the sympathetic nervous system (SNS), which is responsible for the body’s “fight-or-flight” response.

The sympathetic nervous system triggers a cascade of events, including the release of hormones such as adrenaline and noradrenaline. These hormones have several effects on the body: the heart rate increases, blood pressure rises, and the muscles prepare for action. This is why, in moments of stress, we often feel physically “charged up”—our bodies are getting ready for action, whether we need to fight or run away.

Additionally, the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis is activated. This is a system of hormone interactions that involves the pituitary gland and the adrenal glands. The hypothalamus signals the pituitary gland to release adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), which then prompts the adrenal glands to release cortisol, often referred to as the “stress hormone.”

Cortisol: The Stress Hormone

Cortisol is a key player in the body’s response to stress. It serves several important functions, including increasing blood sugar, enhancing brain function, and suppressing non-essential systems like digestion or the immune response. These effects help the body focus its energy on dealing with the immediate stressor.

While cortisol is essential for short-term survival, prolonged exposure to high levels of cortisol can have detrimental effects. Chronic stress leads to consistently elevated cortisol levels, which can impair immune function, increase the risk of cardiovascular disease, and contribute to anxiety and depression.

The Autonomic Nervous System: Fight or Flight vs. Rest and Digest

The autonomic nervous system (ANS) plays a crucial role in regulating the body’s involuntary functions, such as heart rate, digestion, and breathing. The ANS has two primary branches: the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) and the parasympathetic nervous system (PNS).

As mentioned, the SNS is responsible for the “fight or flight” response, preparing the body to take immediate action in times of stress. On the flip side, the PNS governs the “rest and digest” functions, helping the body relax and recover after a stress response.

Ideally, the SNS and PNS work in balance, switching between the two systems as needed. However, if stress becomes chronic, the body may remain stuck in a state of heightened SNS activity, leaving little room for the PNS to restore balance. This can lead to feelings of burnout, exhaustion, and other health problems.

The Physical Effects of Stress on the Body

While stress primarily affects the brain and nervous system, it also takes a significant toll on the body. Let’s explore some of the most common ways stress manifests physically.

The Cardiovascular System

One of the most immediate physical reactions to stress is an increase in heart rate and blood pressure. When the body perceives a threat, the heart pumps faster to deliver more oxygen-rich blood to the muscles, preparing for physical action. However, prolonged stress can lead to chronically high blood pressure (hypertension), which in turn increases the risk of heart disease and stroke.

The Immune System

In the short term, stress can boost the immune system by stimulating the production of white blood cells. This makes sense from an evolutionary standpoint—if you’re injured or exposed to pathogens during a stressful event, your immune system needs to be on high alert.

But when stress is chronic, the opposite occurs: the immune system becomes suppressed. Prolonged exposure to cortisol weakens the immune system’s ability to fight off infections, making you more susceptible to illness. This is why people often get sick after a stressful period.

The Digestive System

Stress also impacts the digestive system. When the body is under stress, digestion is put on hold, as resources are redirected to more immediate needs, like muscle strength and alertness. This is why stress often leads to gastrointestinal problems such as bloating, constipation, diarrhea, and indigestion.

Chronic stress can also contribute to more serious digestive conditions like irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). The imbalance in the autonomic nervous system, with too much sympathetic activity and too little parasympathetic activity, contributes to this disruption in digestive health.

The Musculoskeletal System

Muscles are particularly susceptible to stress. The body’s “fight or flight” response tenses the muscles, preparing for action. However, when this tension is sustained over time due to chronic stress, it can result in muscle pain, stiffness, and even conditions like tension headaches or temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disorders.

The Psychological Impact of Stress: Why You Snap

While the physical effects of stress are significant, the psychological effects are equally profound. Prolonged stress can alter brain function and lead to emotional and mental health problems.

Stress and the Brain

The brain’s response to stress is complex. Chronic stress can alter the structure and function of the brain, particularly in areas responsible for emotion regulation, memory, and decision-making. The hippocampus, which is involved in memory formation, can shrink in response to prolonged stress. This might explain why people under long-term stress often experience memory problems or difficulty concentrating.

Additionally, the amygdala, the brain’s “fear center,” becomes hyperactive during times of stress. This increased amygdala activity can lead to heightened anxiety and irritability. It also explains why, when under stress, people are more prone to emotional outbursts or snapping over seemingly minor issues.

Stress, Anxiety, and Depression

Chronic stress is closely linked to the development of mental health disorders like anxiety and depression. When the brain is continually flooded with stress hormones like cortisol, it disrupts the delicate balance of neurotransmitters such as serotonin and dopamine—chemicals that regulate mood.

This imbalance can result in feelings of sadness, hopelessness, and a lack of motivation, all hallmark symptoms of depression. Likewise, the heightened amygdala activity can make a person more anxious and prone to worrying, often about things that wouldn’t normally be cause for concern.

Why Do People “Snap” Under Stress?

It’s a common experience: one minute, everything seems manageable, and the next, we lose control over our emotions, snapping at a colleague, loved one, or even a stranger. Understanding why this happens lies in the complex interplay between the brain and body during times of stress.

The Breaking Point

When the body is under constant stress, there’s a gradual depletion of resources. Your reserves of energy, patience, and mental clarity start to run low. Small irritations that might otherwise be ignored become the tipping point. This is why people sometimes snap when the pressure becomes too much to bear—it’s not necessarily the last straw that causes the breakdown, but rather a culmination of accumulated stress over time.

Additionally, when we experience chronic stress, the brain’s capacity to regulate emotions becomes impaired. The prefrontal cortex, the region of the brain responsible for higher-level thinking and self-control, is often compromised under stress, making it harder to think rationally or control impulsive reactions. This can lead to emotional outbursts, poor decision-making, and a loss of composure.

Coping with Stress: Rebalancing the System

The good news is that stress is manageable. While we can’t always avoid stressors in life, we can learn to cope with them in healthier ways. By understanding the biological processes behind stress, we can begin to use strategies that activate the parasympathetic nervous system and bring our bodies back into balance.

Mindfulness and Meditation

One of the most effective ways to reduce stress is through mindfulness and meditation. These practices focus on calming the mind, slowing the breath, and shifting focus away from stressors. They can activate the parasympathetic nervous system, helping the body return to a state of rest and relaxation.

Exercise

Physical activity is another powerful stress-reliever. Exercise helps release endorphins, natural mood boosters, and promotes the flow of blood and oxygen throughout the body. Regular physical activity can also help regulate cortisol levels and improve overall physical health.

Sleep and Recovery

Sleep is one of the most important factors in managing stress. When we don’t get enough sleep, cortisol levels rise, and the body’s stress response becomes more pronounced. Adequate rest is essential for rebalancing the body and mind, allowing the brain to repair itself and the body to restore its energy levels.